In Depth

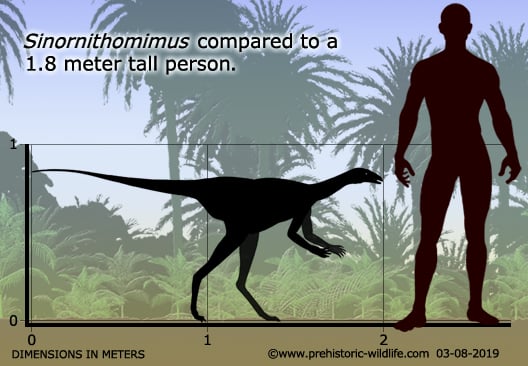

Surprisingly what is perhaps the most important ornithomimosaur so far discovered by the early twentyfirst century is also one of the least known outside of palaeontology. Initially thought to be a primitive ornithomimosaur, Sinornithomimus is now thought to be quite a bit more advanced than early ornithomimosaurs like Harpymimus, but not quite as advanced as those that lived towards the end of Cretaceous such as Ornithomimus. This intermediate development might also support an intermediate placement during the Turonian period of the Cretaceous which is roughly the half way mark between primitive and advanced ornithomimosaur forms. A feature that makes Sinornithomimus immediately stand out from other forms is the neck that is much shorter in proportion to the body than in other forms.

The first thing that made palaeontologists sit up and take note about Sinornithomimus is how individuals of this genus were found. The first discovery by Dong Zhiming (after whom the type species is named) was not of one but fourteen individuals, eleven of which were juveniles while three were subadults, possible adults. Amazingly in 2001 another expedition made a near identical discovery when a group of thirteen juveniles were discovered. Additionally neither of these groups has been interpreted as being a slow and steady build-up of individuals, but instead of groups that were subjected to sudden or fast acting phenomena that killed all the group members within a similar time period. Current thinking has the Sinornithomimus groups stuck in mud in an aquatic environment where they eventually died from starvation or possible predation because they could not escape. Some remains seem to have been pulled about and scattered, especially in the upper body areas which is seen as a sign of scavenging.

As you have probably already noticed the key thing here is that most of the group members were juveniles with only a few near adult individuals. Before there was speculation that ornithomimosaurs went around in family groups with support for the idea coming from some genera such as Gallimimus, but two collections of juvenile groups suggests that as soon as juveniles were independent enough to move around and feed by themselves they left their parents to join up with other juveniles where they would live together until adulthood. This behaviour is not that farfetched when you consider that many types of birds do exactly this today, the benefits being that the parents are then free to raise another brood rather than continue to look after the previous year’s young. Once they had turned adult, Sinornithomimus would have left these juvenile groups, but may still have formed loose groups with other adults before pairing up with another and raising their own brood so that the cycle continues to repeat itself.

The above would suggest that Sinornithomimus and possibly other ornithomimosaurs relied upon what is called an r-strategy survival mode. In the simplest terms this is where parent animals raise a relatively large number of offspring each year with the expectation that many to most of them won’t survive to adulthood. The fact that two groups of juveniles were killed together by what seems to have been a naturally occurring event would suggest that the environment did contain hazardous areas that could easily catch out and cause the deaths of the animals living there. Clustering in groups meant that Sinornithomimus would have had better protection from predatory dinosaurs of the time such as Shaochilong and Chilantaisaurus. Many individuals looking for danger are more likely to spot it than just one and predators always have a harder time keeping their focus upon a targeted individual when it is moving around within a group. This is not always successful however and predators are sometimes successful in striking a group, especially when an individual gets separated. The first groups remains where only three subadults were present may be indicative that the others had already left to start their adult lives, or that they simply didn’t make it that far.

Another thing area that Sinornithomimus has helped to fill in the gaps is gastroliths. For those who are not familiar, gastroliths are stones which are swallowed and stored in the stomachs of some animals that usually cannot process food in their mouths by chewing, so they rely upon the grinding action of the stones moving around in their stomachs to do the job for them. Most, particularly the more advanced form ornithomimosaurs did not have teeth, just a keratinous beak that allowed them to grip and snip things. Beaks however are good for a variety of dietary options from plants to small animals and carrion, so exactly what ornithomimosaurs ate has always remained a mystery. Because gastroliths are most commonly found in herbivorous (plant eating) animals this has led to speculation that Sinornithomimus at least may have been more herbivorous than the omnivore that eats both plants and animals that other ornithomimosaurs are depicted as being.

However, while it’s very possible that Sinornithomimus was a plant eater, it is not unknown for predatory animals to also have them. Animals that eat fish and invertebrates for example often swallow stones to rub off scales and wear down and crack shells and the fossils remains of aquatic crustaceans were found along the Sinornithomimus revealing that they were at least present. Very primitive ornithomimosaurs like Pelecanimimus are also thought to have been fish eaters which further establish a link to a predatory past of the ornithomimosaur group. It would also make more sense for juvenile animals to feed upon animal protein as this would have a much higher nutritional gain for them than eating plants. Again looking at birds, many species will only feed their young invertebrates when they are in the nest, but will also incorporate seeds and green shoots into their diets when adult. Going a little bit further away from Sinornithomimus, there is evidence of a large predatory theropod from Portugal called Lourinhanosaurus which also seems to have had gastroliths within its stomach.

While the gastroliths within Sinornithomimus can be interpreted as being for herbivory, they can also be interpreted in other ways including carnivory or omnivory like with other ornithomimosaurs. Further remains may yet one day reveal a more definitive answer. Another ornithomimosaur that has been found with gastroliths is Shenzhousaurus.

Further Reading

– A new ornithomimid dinosaur with gregarious habits from the Late Cretaceous of China. – Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 48(2):235-259. – Y. Kobayashi & J. Lu – 2003.