In Depth

Although discovered in 1972, Gallimimus was a relatively little known dinosaur until its appearance in the 1993 movie blockbuster Jurassic Park. In one of the more famous scenes of this film a whole herd of Gallimimus gets chased by the Tyrannosaurus before one slips and is killed by this predator. Although science fiction, this scene might not be too far off the mark as a tyrannosaur named Tarbosaurus did roam Mongolia at the same time as Gallimimus and there has been speculation that Tarbosaurus might actually represent an Asian species of Tyrannosaurus.

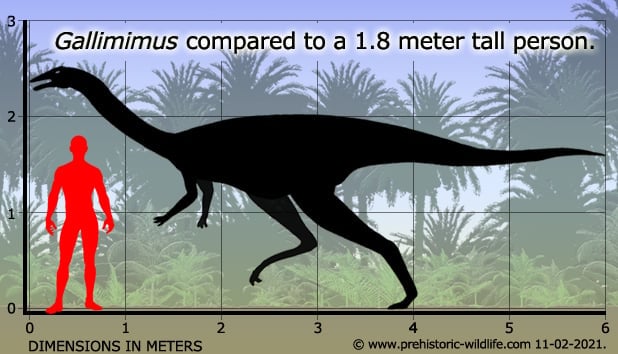

Gallimimus is what is called an ornithomimid dinosaur, a group of specially adapted lightweight theropods that became one of the more common dinosaur types towards the end of the Cretaceous period. Of these Gallimius was one of if not the biggest of the group, often credited at being six meters long but with other fossil material indicating a larger size of up to eight meters long. Mongolia seems to have had the right conditions for freak giant dinosaur genera with another example being Gigantoraptor, a giant oviraptorid when compared to other dinosaurs of its kind. To date the only other contenders for an even larger ornithomimids are Beishanlong and Deinocheirus.

Key to the survival strategy of Gallimimus, and other ornithomimids, was speed. The legs especially the lower portions were long and capable of covering a lot of ground with each stride. The bones like in all theropods were hollow in order to reduce the overall weight of the body so that less energy was required to move and faster running speeds could be maintained. The main body however was proportionately longer than other related genera, and this may have had an impact upon how tight Gallimimus could turn. This may not have been so much of a hindrance however as much of Mongolia during the Cretaceous was open arid plain and realistically all Gallimimus would have to do to survive would be to outpace their potential predators.

Like with all ornithomimids, there is no universal agreement upon what Gallimimus actually ate. The overall size of the skull is small in proportion to the body, but the snout is still longer than most other ornithomimids. The jaws were fashioned into a toothless keratinous beak, and without teeth of a certain kind, it is impossible to establish what Gallimimus ate without the evidence of stomach remains to give further clues. One thing that can be established is that the ‘beak’ could have been used to either pick out plant parts, or even pick up small animals. The size of the skull while small was still large enough to pick up small lizards, snakes and even mammals that realistically would have had to be swallowed whole since there were no teeth to process the bodies. Additionally the point of articulation in the jaws was so rigid that Gallimimus could do little more than open and close its mouth. If Gallimimus and other ornithomimids did indeed hunt small animals then they may have killed them by picking them up and throwing them hard against the ground in a similar way to how South American seriema birds do today (which are also seen to being analogous to the phorusrachid terror birds that lived after the dinosaurs). A final dietary option for Gallimimus would be to raid the nests of other dinosaurs for eggs. Gallimimus also had long arms and fingers, features that could have been used for raking up plants from the ground or perhaps even grasping other things such as eggs so that Gallimimus could run and eat away from the attentions of angry parents. One possible counter against the predatory hypothesis is that Gallimimus had eyes that faced out to either side rather than forwards. This means that Gallimimus had a very wide field of view with which it would have had an easier time spotting threats, but lacked the detailed depth perception that is a hallmark of specialised predatory animals. Despite this however, the nearest living analogy, birds, often have this eye arrangement yet are still capable of hunting other small animals and invertebrates.

Because juvenile Gallimimus have been found, it is possible to get an idea of how this genus and other ornithomimids as a group developed over different life stages. It now also seems that Gallimimus and ornithomimds in general may have had primitive downy feathers that insulated their bodies, however it is still uncertain if fully grown adult Gallimimus retained feathers, as the larger an animal gets, the less it needs hair or feather to the point where the presence of these features may actually become a hindrance.

A second species of Gallimimus (G. mongoliensis) was suggested by Rinchen Barsbold in 1996, but in 2006 Barsbold changed his mind and declared the remains to be an as yet unknown ornithomimid dinosaur.

Further Reading

– A new dinosaur, Gallimimus bullatus n. gen., n. sp. (Ornithomimidae) from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia. – Palaeontologia Polonica 27: 103-143. – H. Osm�lska, E. Roniewicz & R. Barsbold – 1972. – X-ray microanalysis of fossil dinosaur bone: age differences in the calcium and phosphorus content of Gallimimus bullatus bones. – Folia Histochemica et Cytobiologica. 25 (3–4): 241–244. – R. Pawlicki & P. Bolechała – 1987.- X-ray microanalysis of fossil dinosaur bone: age differences in lead, iron, and magnesium content. – Folia Histochemica et Cytobiologica. 29 (2): 81–83. – R. Pawlicki & P. Bolechała – 1991. – Lower jaw of Gallimimus bullatus, by J. Hurum. – In, Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 34–41. – D. H. Tanke, K. Carpenter & M. W. Skrepnick (eds.) – 2001. – Ornithomimids from the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia. – Journal of the Paleontological Society of Korea. 22 (1): 195–207. – Yoshitsugu Kobayashi & Rinchen Barsbold – 2006. – Theropod trackways associated with a Gallimimus foot skeleton from the Nemegt Formation, Mongolia. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 494: 160–167. – Hang-Jae Lee, Yuong-Nam Lee, Thomas L. Adams, Philip J. Currie, Yoshitsugu Kobayashi, Louis L. Jacobs & Eva B..Koppelhus – 2018.