In Depth

Lourinhanosaurus is a tantalising enigma for palaeontologists as although vastly incomplete the remains seem to reveal a sinraptorid theropod (the theropod group typified by Sinraptor). If true then this would make Lourinhanosaurus the first sinraptorid to be discovered outside of China, but other palaeontologists have suggested that Lourinhanosaurus might also be a megalosauroid (more closely related to Megalosaurus).

Classification issues aside, the discovery that really made palaeontologists scratch their heads were the presence of gastroliths in association with the Lourinhanosaurus remains. In an herbivorous dinosaur this would not be that unexpected, but the fragmentary remains of Lourinhanosaurus are enough to reveal a theropod of the kind that has been dug up the world over as a meat eater. Additionally palaeontologists are quite satisfied that the stones could not have been swallowed accidentally when the individual fed upon a herbivorous dinosaur.

However while it is unusual for a predator to use gastroliths, it is not altogether unknown. The grinding effects of the stones would have been able to tenderise meat that had been swallowed, useful since predatory dinosaurs were not good at chewing and they could at best only swallow chunks of meat. It is also perhaps not impossible that Lourinhanosaurus was a specialised predator that might have eaten crustaceans and shellfish which needed gastroliths for the shells to crack. Unfortunately this is pure speculation in the absence of the parts that could answer the question. Without a skull, it would be impossible to identify any specialised feeding adaptations, and other remains with the gastroliths might reveal parts of what was inside the stomach at the time of death, but these first need to be found.

One final thing to remember upon this subject is that during the Jurassic Europe was not a single large land mass like it is today, and an animal that could adapt to different food sources, particularly the creatures like one might expect upon a beach ecosystem, would have an advantage in the survival stakes. It could also be that Lourinhanosaurus like other theropod dinosaurs may have changed its ecological niche during different phases of its life. Tyrannosaurs by example seem to have been very fast and agile predators when only a few years old, making them well suited for chasing the smaller and faster ornithopod dinosaurs. In later life they grew much bigger and no longer had the agility to hunt these swifter dinosaurs which also no longer offered a sufficient return in calories, so the adults switched to hunting larger and heavier dinosaurs. This niche specialisation also allowed juveniles and adults of the same species to coexist in the same ecosystem without competing with each other for the same food.

When younger and smaller, Lourinhanosaurus may have frequented coastal environments which were far more extensive in Jurassic Europe. Here they would be able to feed by either hunting smaller dinosaurs or raiding tidal pools for fish and crustaceans, the latter two choices requiring the use of gastroliths. Lourinhanosaurus that survived to adulthood may have grown too large to support themselves by this and switched to a greater reliance upon hunting other dinosaurs, again the two generations avoiding competition with one another for the same resources.

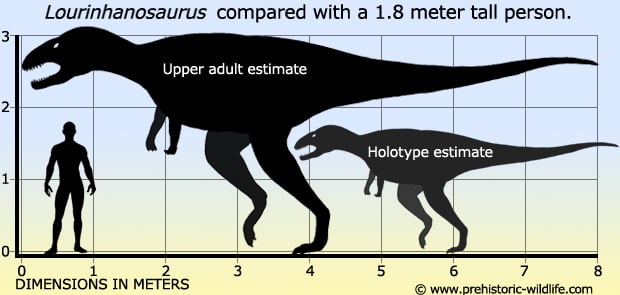

Lourinhanosaurus is usually credited at being around four and a half meters long and this is certainly true for the type specimen. The type specimen however is thought to represent an immature individual and later analysis and study has led to an upper estimate of eight meters long for an adult individual. This would make Lourinhanosaurus a large theropod dinosaur for the Jurassic, but within the realms of upper size for the European theropods.

The discovery of around a hundred eggs, some of which contain fossilised embryos has been very exciting. These eggs are around thirteen centimetres long and were attributed to Lourinhanosaurus on the grounds that they were found not far away from the Lourinhanosaurus type specimen.

Further Reading

– Lourinhanosaurus antunesi, a new Upper Jurassic allosauroid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from Lourinh� (Portugal) – Mem�rias da Academia de Ci�ncias de Lisboa 37: 111–124. – O. Mateus – 1998. – Upper Jurassic theropod dinosaur embryos from Lourinh� (Portugal) – Mem�rias da Academia das Ci�ncias de Lisboa 37, 101-110. – I. Mateus, H. Mateus, M. T. Antunes, O. Mateus, P. Taquet, V. Ribeiro & G. Manuppella – 1998. – Upper Jurassic dinosaur and crocodile eggs from Paimogo nesting site (Lourinh�- Portugal). – Mem�rias da Academia de Ci�ncias de Lisboa 37: 83–100. – M. T. Antunes, P. Taquet & V.Ribeiro – 1998. – The Large Theropod Fauna of the Lourinha Formation (Portugal) and its Similarity to the Morrison Formation, With a Description of a New Species of Allosaurus – J. R. Foster & S. G. R.M. Lucas, eds., Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 36. – O. Mateus, A. Walen & M. T. Antunes – 2006.