In Depth

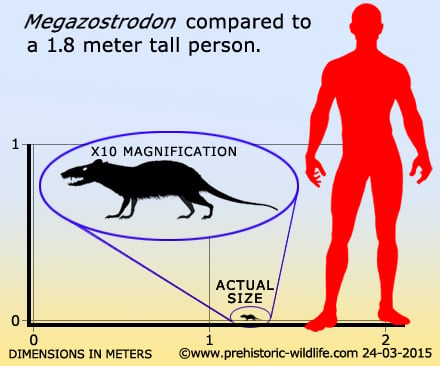

When you look up the first true mammals in dinosaur books you almost certainly going to be presented with a picture and brief description of Megazostrodon. Modern analysis of Megazostrodon has it in a position that is almost fully mammal, yet not quite. True mammals begin with the triconodont group, something that the Megazostrodontidae used to belong to until analysis placed it just outside.

Despite the revised classification, Megazostrodon’s adaptations are almost totally mammalian, and it continues to be a strong transitional form between the earlier therapsids and true mammals. The first key area is that the mandible (lower jaw) became one single bone rather than the seven seen in reptiles. However these bones were not lost they actually got rearranged to form the middle ear, becoming the mammalian hearing system. Megazostrodon also had a covering of hair over its body, something that was not necessarily new as suggested by Thrinaxidon and Cynognathus, but still a clear mammalian trait.

The reduction of the ribs and enlargement of the lungs points towards a development for a faster rate of respiration. This is of particular importance when you realise that a faster rate of respiration is required to support an endothermic (warm-blooded) metabolism. Ectothermic (cold-blooded) metabolisms by comparison are generally slower and do not require such a high intake of oxygen to burn food for energy.

Connected to the support of a warm blooded metabolism are the teeth which can be arranged into clear incisor, canine, pre-molar and molar groups. This allowed for efficient processing of food such as insects that would require incisors and canines for capture and killing, and the molars for crunching the hard exoskeleton. By chewing small prey like insects Megazostrodon would have a high protein diet that would be quickly digested, a more efficient system that supplied the increased demands of a faster metabolism. There are still two key reptilian features of Megazostrodon, and one is the way the legs sprawl outwards. Although the limbs are not as pronounced as the earlier therapsids they still do not support the body from directly underneath. This in mind however, the skeletal joints do indicate a greater amount of movement was possible, something that would increase the agility of Megazostrodon. The second feature is that Megazostrodon is thought to have still laid eggs like a reptile. However while it may sound strange for a mammal to lay eggs, monotremes like the platypus and echidna are mammals that do lay eggs today.

Despite the egg laying Megazostrodon is thought to have suckled its young, something that would continue all the way down the line to mammals today. By being warm-blooded Megazostrodon is also thought to have been nocturnal so as to avoid the cold-blooded predators that would have been active during the day perhaps like the newly evolving dinosaurs or other carnivorous archosaurs.

The dating of the Megazostrodon specimen places it around two hundred million years ago, placing it just over into the Triassic of the Jurassic/Triassic boundary. The immediate future of the new mammalian creatures would be a small one that saw them scurrying around trying to stay out of sight. Even a hundred and forty million years later towards the end of the Cretaceous, the larger mammals like Didelphodon would only attain sizes of up to thirty centimetres. Despite these small sizes the mammals would quickly form an important part of the ecosystem, keeping the number of insects down as they fed upon them and in turn being food for other predators like the dinosaurs, something which has be learned from the presence of Zhangheotherium and Sinobataar remains inside the dinosaur Sinosauropteryx.

Further Reading

– Molar occlusion in Late Triassic mammals. – Biological Reviews 43:427-458. – A. W. Crompton & F. A. Jenkins – 1968.