In Depth

Cynognathus seems to be one of the most successful of the cynodonts, with a large number of fossil remains from a wide geographic distribution being all attributed to the genus. There is however some controversy over whether all of these fossils should be labelled as Cynognathus, as the genus does seem to have suffered from the ‘wastebasket taxon’ effect.

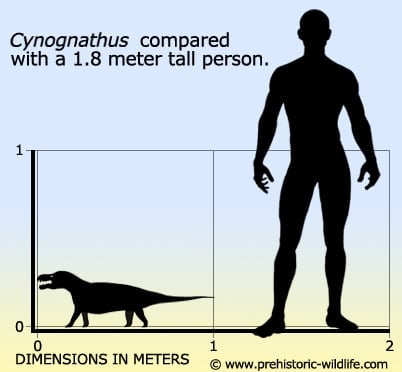

Despite this the appearance of Cynognathus is known without doubt. In general appearance Cynognathus was a stocky animal with a proportionately large skull that made up thirty per-cent of the total body length. The skull was robust and was likely capable of inflicting powerful bites. The teeth were sharp, and slightly re-curved, and driven by the jaw muscles were easily capable of piercing the tough hides of the known herbivores of the early Triassic. In addition they was some variance in the form of the teeth suggesting that Cynognathus processed food by jaw movement, cutting meat up into smaller bits rather than just trying to swallow chunks whole. The skull also features a hard secondary palate, something that proves that Cynognathus would have still been able to breathe when the mouth was full of food. The post cranial skeleton of Cynognathus is also quite interesting. The ribs do not extend into the abdomen which means two things. One is that Cynognathus likely had a diaphragm, a sheet of muscle that separates the lungs from the lower organs, a feature commonly seen in mammals that aids in respiration. Two is that the lower body would have been much more flexible thanks to the absence of the ribs. The rear legs of Cynognathus supported the hind quarters from underneath, but at the same time the front legs sprawled out to the sides like in more primitive therapsids. Although Cynognathus might have been an unusual runner, it was almost certainly fast enough to catch other therapsids.

Further Reading

Researches on the Structure, Organization, and Classification of the Fossil Reptilia. Part IX, Section 5. On the Skeleton in New Cynodontia from the Karroo Rocks. - Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 186:59-148 - Harry Govier Seeley - 1895. – The first occurrence of Cynognathus crateronotus (Cynodontia: Cynognathia) in Tanzania and Zambia, with implications for the age and biostratigraphic correlation of Triassic strata in southern Pangea. – B. M. Wynd, B. R. Peecock, M. R. Whitney & C. A. Sidor, In Vertebrate and Climatic Evolution in the Triassic Rift Basins of Tanzania and Zambia. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Memoir 17. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 37(6, Supplement) pp. 228–239, C.A. Sidor & S.J. Nesbitt (eds.) – 2018.