In Depth

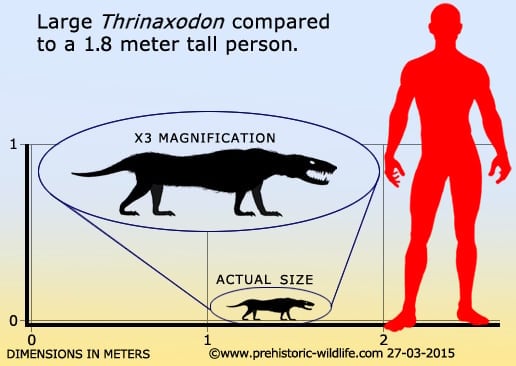

As a cynodont Thrinaxodon was the result of the on-going evolution of mammal like reptiles that had can be traced all the way back to the early synapsids. Thrinaxodon however displays numerous features that place it much closer to mammals than its reptile origin would imply.

The first and most evolutionary significant feature of Thrinaxodon is the division of the main body into thoracic and abdominal areas. In earlier animals the ribs extended down from all of the vertebrae usually ending where the sacrum (pelvis) begins resulting in a rib cage that ran the entire length of the main body. In Thrinaxodon however the ribs only drop down from the frontal dorsal vertebrae, the dorsal vertebra between these and the sacrum being devoid of ribs. This meant that the key organs like the lungs and heart were still protected by the ribs while the intestines were not. It has also been speculated that a muscular diaphragm would have been present to separate these two areas.

Another feature to take note of are small pits in the snout of the skull. These seem to have been the anchor points for whiskers. The presence of whiskers denotes the ability to grow hairs, and while fossils have not yet been found to prove the existence of anything other than these whiskers, it’s certainly possible that Thrinaxodon may have had a coat of hair in life. Hairs would have developed to serve a purpose, possibly for insulation which may suggest a warm blooded metabolism.

Thrinaxodon had a secondary palate that allowed the nasal passages to be separate from the mouth. This means that no matter how long Thrinaxodon kept food in its mouth for it could still breathe. Mashing food in the mouth for longer would reduce the amount of time necessary for digestion. This also suggests a faster metabolism that needed a quicker intake of energy and nutrients in order to maintain its speed.

Apart from suggesting a warm blooded metabolism as found in true mammals, these adaptations also point to a lifestyle that could see Thrinaxodon living in burrows to survive. Firstly the division of the body into abdominal and thoracic area with a rib cage (and least flexible part of the body) meant that Thrinaxodon would have been able to turn around in a much tighter space like a tunnel. This is a feat that would have been physically impossible for a creature with the older arrangement of ribs all the way to the sacrum.

You also need to consider the development of whiskers. Whiskers are sensory hairs that radiate out so that an animal knows if a gap or hole is wide enough for them to pass through. If the animal cannot pass through without the whiskers getting bent back it either avoids going down or digs the hole wider.

Another thing to look at is the overall shape and proportions of the body. The legs are short and do not sprawl out wide to the sides. The tail is also reduced and the body is proportionately much longer than it is wide. This shape allows for much more efficient travelling down narrow tunnels. Living in tunnels would also have been a good survival strategy as archosaurs were roaming the land always on the lookout for easy Thrinaxodon sized meals.

Thrinaxodon itself was probably a generalist of small prey items like lizards and invertebrates. The arrangement of small sharp teeth would have been better suited for these kinds of prey, which themselves would have provided a high protein diet better suited for maintaining a fast metabolism. If Thrinaxodon was indeed a burrowing animal it may have remained in the burrow during the daytime coming out to feed at night where it could use the cover of darkness to hide its activities. Even so, Thrinaxodon probably would not stray too far from the burrow.

Further Reading

– Researches on the Structure, Organisation, and Classification of the Fossil Reptilia. Part IX. Section 1. On the Therosuchia. – Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B 185:987-1018. – Harry Govier Seeley – 1894. – Note on a new skeleton of Thrinaxodon Liorhinus. – A. S. Brink – 1959. – Cranial anatomy of the cynodont reptile Thrinaxodon liorhinus. – Museum of comparative Zoology, Harvard University, 125: 165-180. – R. Estes – 1961. – Growth patterns of Thrinaxodon liorhinus, a non-mammalian cynodont from the lower Triassic of South Africa. – Paleontology. 48(2): 385-394. – J. Botha & A. Chinsamy – 2005. – Ontogeny of the Early Triassic Cynodont Thrinaxodon liorhinus (Therapsida): Cranial Morphology. – The Anatomical Record. – Sandra C. Jasinoski, Fernando Abdala & Vincent Fernandez – 2015.