In Depth

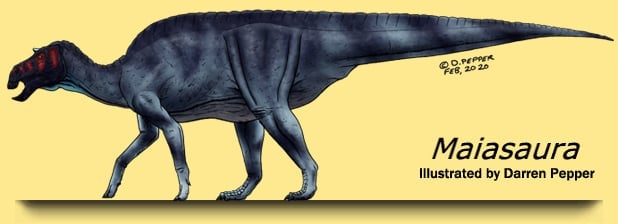

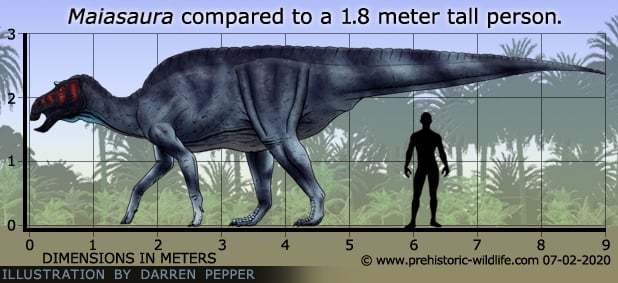

At up to nine meters long Maiasaura was not amongst the largest known hadrosaurid dinosaurs, though it still tipped the scale to be considered big for its kind. Like with its hadrosaurid relatives, Maiasaura is thought to have been a primarily bipedal dinosaur, though one that was at least capable of balancing if not walking upon just its hind legs. The exact posture assumed was probably more dependent upon what the Maiasaura in question was actually doing at the time. Maiasaura had a low crest on top of it snout and because it is solid, this indicates that Maiasaura was one of the saurolophine hadrosaurs.

Maiasaura might appear to be a rather plain looking hadrosaurid, but its real importance is not about its looks but upon the remains of nests that members of this genus created. One of the most significant fossil sites associated with Maiasaura is an area that we know today as ‘Egg Mountain’. Here a concentration of nests spread apart at distances of around seven meters from each other, each containing around thirty to forty eggs about fifteen centimetres across were found with multiple remains of Maiasaura scattered around them. Some of these remains were of juveniles too large to have just hatched with underdeveloped rear legs. The skulls of juveniles also have very different proportions to those of the adults, though this is quite common in vertebrates. In addition to these were remains of adult Maiasaura, something that suggests that adults would not just lay their eggs and wander off, but stay close to the nests and their young for some time. Bearing in mind the underdeveloped rear eggs of the younger juveniles it’s possible that a more precise scenario is that the adult Maiasaura would move away from the nests for short periods while they foraged to bring food back to the nest while the hatchlings became strong enough to walk around and forage for themselves.

The sheer number of nests and Maiasaura fossils from the Egg Mountain site is proof that Maiasaura would congregate in large numbers during the nesting period, however it remains impossible to say for certain how this genus lived when not nesting. It’s not impossible that when Maiasaura were not nesting they moved around in much smaller groups to reduce the impact on the ecosystem in a given area, more mouths in one place would after all cause more destruction to the plants growing there, increasing the amount of time necessary for the ecosystem to recover, although hadrosaurids like Maiasaura might have been continually on the move and only staying put for short periods such as nesting.

A modern analogy to this would be some species of birds (particularly sea birds where the effect can most appreciated) where during the year birds will form small concentrations with loose bonds between individuals, but will once a year congregate upon a single area where conditions are ideal for raising young. Due to the rarity of such places, a higher number of birds move into a specific area that can give observers who are not familiar with the life practices of the birds during the remainder of the year the false impression that the birds always live in such high concentrations.

It’s probable however that Maiasaura, and other hadrosaurids, were not solitary creatures given that they have no obvious physical defences from attacks by predators (such as the thick armoured plates of ankylosaurs). The best bet for Maiasaura to stay alive in a world of large predators would be to stay in groups from a few individuals to perhaps as many as dozens or even hundreds of individuals. This way you would have more than one set of eyes for seeing predators, more than one nose for smelling predators, and more than one pair of ears for hearing predators, altogether making it significantly harder for a predator to get in close for a surprise ambush. Multiple individuals moving and calling out all at once would also make it significantly harder for predators to single out a specific individual for attack.

With the exception of Maiasaura, another hadrosaurid called Hypacrosaurus has also allowed palaeontologists to look at nesting patterns within this group of dinosaurs. Additionally this hadrosaurid along with another named Prosaurolophus appear to have been present at roughly the same time and location as Maiasaura. It’s possible that Maiasaura may have shared its habitat with its close relative Edmontosaurus, however the earliest known specimens of Edmontosaurus are thought to be around seventy-three million years old, while known Maiasaura remains are dated one to two million years earlier. An alternative theory is that the larger Edmontosaurus may have replaced Maiasaura in the ecosystems, especially in the advent of larger late Cretaceous predators such as Albertosaurus and Tyrannosaurus dominating the landscape.

Other herbivores active around the same time and location as hadrosaurs include centrosaurine dinosaurs such as Styracosaurus, Achelousaurus, Einiosaurus and Leptoceratops as well as armoured dinosaurs such as Euoplocephalus and Edmontonia. Dinosaurs that may have been actual threats to Maiasaura however include the Troodon and Daspletosaurus and possibly Gorgosaurus.

Maiasaura stands out as a name because it does not end with a ‘rus’ like the more familiar saurus. This is because Maiasaura is intended as a feminine name which is why it ends in saura rather than the masculine saurus.

Further Reading

- Nest of juveniles provides evidence of family structure among dinosaurs, J. R. Horner & R. Makela - 1979. – Maiasaura, a model organism for extinct vertebrate population biology: A large sample statistical assessment of growth dynamics and survivorship. – Paleobiology. 41 (4): 503–527. – Holly N. Woodward, Elizabeth A. Freedman Fowler, James O. Farlow & John R. Horner – 2015.