In Depth

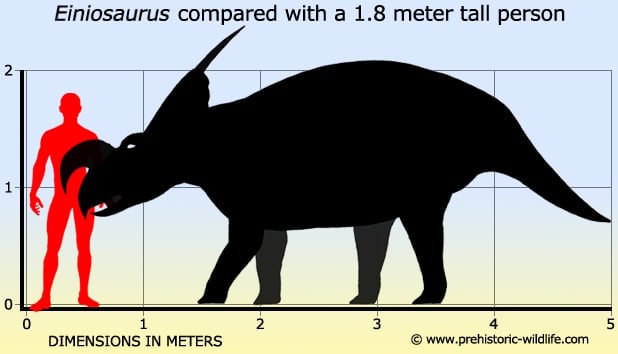

The nasal horn of Einiosaurus is quite unusual in that it curves forward to point towards the ground, something which is reflected in the species name E. procurvicornis which translates to English as ‘forward curving horn’. In young Einiosaurus this horn is thought to have started out small, but as the individual grew the horn got larger and more curved until it reached the extremes in what are thought to be adult specimens. This strongly suggested that the curved horn was a sexually selected characteristic that was most developed in the largest and most mature individuals, although it is not certain if males and females shared the same level of development.

The curving of this horn is thought to have ultimately evolved to touch upon itself to form the nasal bosses that are present in other related centrosaurine ceratopsians like Pachyrhinosaurus and Achelousaurus. Ultimately this suggests that Einiosaurus was more basal than pachyrhinosaurine members of the Centrosaurinae, yet itself was more advanced than others such as Centrosaurus.

As a centrosaurine ceratopsian, Einiosaurus had a short neck frill compared to the chasmosaurine ceratopsians like Chasmosaurus. On the top of this neck frill were two large horns that projected upwards from the top, a feature similar to Diabloceratops. Further smaller horns were placed along the outer edges of the neck frill, and although these horns were most probably for the purpose of display, it’s conceivable that these horns would have offered a little more protection against large tyrannosaurid predators like Gorgosaurus, and particularly Daspletosaurus which was thought to have been better suited to tackling ceratopsians. Still these frill horns may have best only served to intimidate predators rather than being of practical use, especially as part of a herds group display. Herding behaviour has been attributed to Einiosaurus due to the discovery of a bone bed that yielded the remains of at least fifteen individuals. Einiosaurus was the only ceratopsian in this bone-bed, and other micro fossils of aquatic molluscs suggest that the ground would have once been underwater. Two theories exist for this occurrence, the first of which is that a herd of Einiosaurus clustered around a diminishing water hole during the dry season that was not replenished by rain in time to save the herd. Another and often more widely accepted theory is that the Einiosaurus drowned while trying to cross a river, a theory that has been proposed to explain the presence of other ceratopsian dinosaur bone-beds that exist for Centrosaurus and Styracosaurus.

Droughts and flash floods may have been common problems for Einiosaurus to deal with as they seem to have lived in a semi-arid inland environment. Rivers would have not only been one of the few sources of water but also formidable barriers as Einiosaurus moved on to fresh grazing areas. The plants of this environment would have been considerably tougher than the lush vegetation of wetland areas, but Einiosaurus possessed typical ceratopsian features that allowed it to eat these kinds of plants. The first was a sharp beak that was easily capable of shearing through though and fibrous stems. The mouth had a battery of specialised teeth that were easily capable of grinding tough plant material so that it could be easily digested.

The name Einiosaurus is a combination of the Blackfeet ‘eini’ (buffalo) and the Ancient Greek ‘saurus’ (lizard).

Further Reading

– Two new horned dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Ceratopsidae) from the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation, Montana, USA. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 15 (4): 743–760. – Scott D. Sampson – 1995.