In Depth

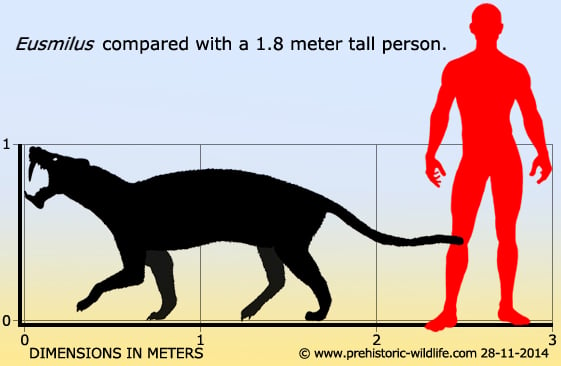

Out of all of the nimravids, mammalian predators better known as the ‘false sabre-toothed cats’, Eusmilus seems to have been one of the most dangerous. Not only did Eusmilus grow to be one of the largest known nimravids at up to two and a half meters long, but a skull of its smaller relative Nimravus has been found with skull damage that is an almost precise match for the teeth of Eusmilus. This however may have been a case of one predator warning another away rather than an attempt of killing to feed since the wounds on the individual Nimravus in question actually healed.

As anyone who is already familiar with nimravids knows, Eusmilus looked like one of the later sabre toothed cats, but was in fact no way related them beyond being a member of the Carnivora. Nimravids like Eusmilus evolved down a separate genetic line, but found themselves living in a world where there was a predatory niche open for cat-like predators. Growing large and possessing enlarged upper canine teeth that were almost as long as the skull, Eusmilus would have been a hunter of other medium to large sized animals.

The enlarged canines that are nicknamed ‘sabre-teeth’ were the primary killing tools employed by Eusmilus and analysis of the skeleton supports this. The muscle attachment points on the skull show that Eusmilus actually had weak jaw closing muscles, but this was to allow for a wide jaw opening angle. Reconstructions of Eusmilus show that its jaw could open to an impressive ninety degrees wide, thirty degrees more than a modern African lion (Panthera leo). However this still pales in comparison to the later Smilodon which had the ability to open its jaws one hundred and twenty degrees wide. These wide jaw opening angles allow for the sabre-teeth to be brought into use without the lower jaw getting in the way. To compensate the weak bite force, the neck and shoulders were designed to allow for powerful downward thrusts that drove the sabre-teeth through its victim without the need for using the jaw muscles. When these teeth punctured a critical area such as neck, death would come in a matter of minutes at most for the prey. Despite their awesome killing power however, the large sabre-teeth of Eusmilus would have been quite weak when subjected to side to side movements and it’s probably that Eusmilus would have had to use its size and strength to physically restrain its prey before trying to use its teeth. This would be a vital precaution to take since if the teeth were broken, Eusmilus really had no other way of efficiently killing prey animals.

This is also why the lower jaw also has two flanges of bone than project downwards. This is because the canine teeth of Eusmilus are so large they would easily clear the bottom of the lower jaw had it not had the flanges, increasing the likely hood of them being broken should Eusmilus get hit in the face by a struggling animal, or colliding with something while it was running after prey. The concept of protecting the canine teeth in this way is such an effective and necessary principal that it occurs in other sabre-toothed mammals such as the South American Thylacosmilus. Whereas Eusmilus is only distantly related to true cats (members of the Felidae), it is even more distantly related to Thylacosmilus since this was a marsupial mammal, while Eusmilus was a placental mammal, a type that appeared after the marsupials. Once again this is another case of convergent evolution since while Eusmilus and other nimravids lived in a world devoid of true cats, Thylacosmilus lived on a continent not only devoid of cats but the nimravids as well, yet all of these predators ended up fulfilling the ecological niche in their habitats.

Further Reading

– The Miocene faunas from the Wounded Knee area of western South Dakota. – Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. – J. R. Macdonald – 1963. – Functional morphology and the evolution of cats. – Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences 8:141-153. – L. D. Martin – 1980. – Taxonomic and systematic revisions to the North American Nimravidae (Mammalia, Carnivora). – PeerJ. 4: e1658. – P. Z. Barrett – 2016.