In Depth

Nimravus - Not a Cat!

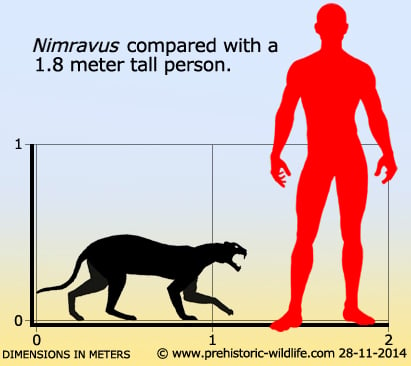

Nimravus is the type genus of the Nimravidae group of mammals that are better known as the ‘false sabre-toothed cats’. This is because while Nimravus and others like it looked like the big cats, they actually evolved from a different line of mammals than the true cats that are members of the Felidae branch. Despite the differing lineage Nimravus developed a body form that was so much like a predatory big cat it leads to the conclusion that the big cat body form is so well suited to the predatory lifestyle that it has independently repeated itself in nature.

Although palaeontologists who specialise in mammals and particularly big cats can identify a number of features different between Nimravus and true cats, there are two main areas that anyone can spot if given the opportunity to study the paws and the inner cranium. First are the paws which are shaped more like those of dogs rather than a cats, something which may imply that Nimravus spent most of its time on the ground rather than climbing into trees like some cats do.

The second identifying feature that tells us Nimravus is not a cat is the construction of the auditory bullae. This is where the inner and middle ear is located, and each one is a hollow chamber on either side of the skull for each ear. In true cats this chamber is divided up into two by a bony septum, but in Nimravus and other nimravids the chamber is preserved as a single hollow. Of course in life this chamber may have still been divided by a cartilaginous septum that did not preserve but it is still enough of a difference to be a defining characteristic between nimravids and true cats.Nimravus the predator

Nimravus was active from the Oligocene to early Miocene and throughout this time it would have been one of the key predators of North America. Perhaps the most interesting predatory adaptations are the enlarged forward canines that look so similar to the sabre teeth of the much more well-known Smilodon (better known as the sabre-toothed cat). Considering that these two genera are not just separated by several million years but also a differing family line, this is a remarkable case of convergent evolution. The fact that Nimravus had these teeth, as well as other unrelated mammals such as the marsupial Thylacosmilus, suggests that hunting with these teeth was a particularly effective way for predators to hunt medium to large mammalian prey, and briefly bringing Smilodon back into the frame, was a technique that disappeared comparatively recently only ten thousand years ago.

Because the feet of Nimravus were more similar to canids and with partially retractable claws, Nimravus is not envisioned as a hunter that crossed vast expanses of ground while chasing after prey. Instead it probably exhibited more cat-like behaviour by lurking amongst long grasses and approaching prey animals from downwind. Once the target animal was close enough Nimravus could launch its attack and cover most of the ground between them before the prey realised what was going on. How the prey was killed remains a controversial subject as there are a number of theories about how a predator with oversized canines like Nimravus could have killed prey without damaging the teeth.

It is possible that in the surprise of the initial attack Nimravus could have delivered a quick but deep bite to an area like the neck that opened up an artery which caused the prey to bleed to death in a few minutes. Alternatively Nimravus may have tried to grapple or cling onto prey and deliver a penetrating bite to an area like the throat that closed the windpipe. However Nimravus was of a more lightweight gracile build than some other nimravids and true cats, so it may have been restricted to tackling smaller and more lightweight prey animals, or the juveniles of larger animals.

Possible prey animals for Nimravus could have included camels like Poebrotherium, or possibly even smaller individuals of oreodonts like Eporeodon. Nimravus was not the only carnivore of these times however as it also would have had to share its habitat with enteledonts, powerfully built carnivores with massive mouths thought to be related to modern pigs, as well as other nimravids. In fact one Nimravus skull has been found with puncture marks from another carnivores teeth in it, and one analysis suggests that they were caused by another nimravid called Eusmilus.

The disappearance of Nimravus at the start of the Miocene period coincides with a shift in the climate of North America towards a dryer and more open expanse of plains. This caused prey animals to change to better cope with this new environment which typically suited longer legged, faster animals that were likely beyond the ability of Nimravus to catch. Additionally, new predators such as ‘bear dogs’ like Amphicyon had made their way across the Bering land bridge into North America, and were starting to displace the older predatory forms from their positions at the tops of the food chains. In this new ecosystem Nimravus found itself obsolete and unable to adapt, its last remains entering the fossil record at the start of the Miocene.

Further Reading

– A Lower Miocene fauna from South Dakota. – Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 23(9):169-219. – W. D. Matthew – 1907. – The species of Nimravus (Carnivora, Felidae). – Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 118(2):71-112. – L. Toohey – 1959.