In Depth

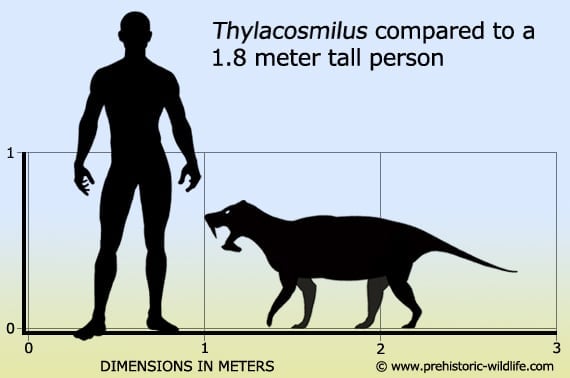

With its oversized front teeth Thylacosmilus appears to be very similar to sabre toothed cats like Smilodon. The key difference between these two types of animal is that the sabre toothed cats were placental mammals, which means that young developed while connected to a placenta via an umbilical cord while remaining inside the mother’s body. Marsupials like Thylacosmilus however have a pouch which young (called neonates) are birthed into at an early stage of development where they remain until they are ready to be upwardly mobile themselves. This means that while it looked similar to a sabre toothed cat, Thylacosmilus was in the same group as modern kangaroos and the extinct Thylacine (better known as the Tasmanian Tiger).

The most striking feature of Thylacosmilus are the teeth, even though they actually only share superficial similarity to those of the sabre toothed cats. One key difference is that the teeth constantly grew throughout the life of Thylacosmilus, meaning that if they were not worn down they would keep on growing larger. Teeth may have been worn down by wear form contact with the bones of prey. The mandible also had two large bone growths referred to as flanges that ran alongside both teeth so they had extra support and protection when the jaw was closed. The jaws could also open to a very wide angle, something that would allow the large teeth to be used efficiently. The price of this wide opening is that Thylacosmilus would have had a reduced bite force. However, this is not a drawback for a predator that relies upon driving through the points of just two teeth to kill its prey, as focusing the force upon just two points would have increased the impact pressure meaning that strong jaw muscles would not have been necessary for an effective bite.

Thylacosmilus may have used the oversized teeth in a similar fashion to the better known sabre toothed cats. This could see Thylacosmilus ambushing prey by either staying low in the vegetation or leaping onto it from above. During these surprise attacks Thylacosmilus could inflict a deep bite to a vulnerable area like the neck, something that could sever arteries that resulted in rapid blood loss. In this Thylacosmilus is usually depicted as a lone hunter, although multiple Thylacosmilus hunting together is not an outright impossibility. Mothers would have hunted with offspring still inside their pouch and may have even been joined by them for a period of time when the young were approaching adulthood. Ultimately it may have been contact with the anatomically similar Smilodon that brought about the downfall of Thylacosmilus. This contact was a product of the Great American Interchange, an event triggered by the joining of North and South America which allowed animals that were once isolated from one another to intermix and spread into new areas. Smilodon was larger and more powerful than Thylacosmilus, and probably had a near identical killing technique and prey preference. When two predators of the same prey animals are in competition to one another it is usually the weaker and less well adapted of the two that disappears.

Climate change is another strong factor as the overall climate where Thylacosmilus is most well-known was starting to become drier as Thylacosmilus began to decline and disappear. While climate usually has little direct impact upon predators, it does have a bigger effect upon prey. The changing types of prey available (as well as increased competition from new predators) may have meant that Thylacosmilus was no longer the efficient killer that it had been in the past. The attrition of living in a world that was becoming harder to live in could have ultimately brought the downfall and extinction of Thylacosmilus.

It is worth remembering that while Thylacosmilus was certainly a formidable hunter, the top predators of South America during the existence of the genus would have actually been large phorusrhacids, more popularly known as ‘terror birds’.

Further Reading

– Preliminary description of a new marsupial sabertooth from the Pliocene of Argentina. – Geological Series of Field Museum of Natural History. 6: 61–66. – Elmer S. Riggs – 1933. – A New Marsupial Saber-Tooth from the Pliocene of Argentina and Its Relationships to Other South American Predacious Marsupials. – Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 24 (1): 1–32. – Elmer S. Riggs – 1934. – Evolution of the Thylacosmilidae, extinct saber- tooth marsupials of South America. – PaleoBios, 23, 1–30. – L. G. Marshall – 1976. – Restoration of masticatory musculature of Thylacosmilus, by W. D. Turnbull. In Athlon, Essays in Palaeontology in Honour of Loris Shano Russell. Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum. pp. 169–185., C. S. Churcher (ed.). – 1976. – Another look at dental specialization in the extinct saber-toothed marsupial, Thylacosmilus, compared with its placental counterparts, by W. D. Turnbull. – In, Development, function and evolution of teeth. Academic Press. pp. 399–414. Percy, Butler, Joysey Milton & Alan Kenneth (eds.). – 1978. – The ear region of the marsupial sabertooth, Thylacosmilus: Influence of the sabertooth lifestyle upon it, and convergence with placental sabertooths. – Journal of Morphology. 181 (3): 239–270. – William D. Turnbull & Walter Segall – 1984. – The brain of Thylacosmilus atrox. Extinct South American saber-tooth carnivore marsupial. – Journal f�r Hirnforschung. 29 (5): 573–586. – J. C. Quiroga & M. T. Dozo – 1988. – Functional-adaptive features and palaeobiologic implications of the postcranial skeleton of the late Miocene sabretooth borhyaenoid Thylacosmilus atrox (Metatheria). – Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 28 (1): 229–266. – Christine Argot – 2004. – Comparative Biomechanical Modeling of Metatherian and Placental Saber-Tooths: A Different Kind of Bite for an Extreme Pouched Predator. – PLOS ONE. 8 (6): e66888. – S. Wroe, U. Chamoli, W. C. H. Parr, P. Clausen & R. Ridgely – 2013. – An eye for a tooth: Thylacosmilus was not a marsupial ‘saber-tooth predator’. – PeerJ. 8: e9346. – Christine M. Janis, Borja Figueirido, Larisa DeSantis & Stephan Lautenschlager – 2020. – The Great American Biotic Interchange revisited: a new perspective from the stable isotope record of Argentine Pampas fossil mammals. – Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 1608. – Laura Domingo, Rodrigo L. Tomassini, Claudia I. Montalvo, D�nae Sanz-P�rez & Mar�a Teresa Alberdi – 2020.