In Depth

Plateosaurus is probably the best understood sauropodomorph dinosaur currently known, and also one of the oldest dinosaur genera. Named in 1837, Plateosaurus actually predated the creation of the Dinosauria by Richard Owen in 1842, though the genus missed out on being one of the defining dinosaur genera (instead Owen used Megalosaurus, Iguanodon and Hylaeosaurus). Regardless of this, study of Plateosaurus has revealed that in terms of contribution to the science of palaeontology, Plateosaurus is one of the most important dinosaurs.

Plateosaurus used to be known as a prosauropod, but modern terminology sees it described as a sauropodomorph. Either way, what this means is that the Plateosaurus genus represents a type of dinosaur that was ancestral to the later and larger sauropods of the Jurassic. The sauropodomorphs also help to reveal how sauropods and theropods have a shared ancestry despite being very different animals in terms of ecological niche.

Plateosaurus are most often associated with central Europe, especially Germany where the bulk of known specimens come from. Remains are known from Greenland however, with other remains speculated from South America. Plateosaurus can also go down in history as being the first dinosaur genus to be found in Norway. The sheer number of Plateosaurus fossils compared with the somewhat limited remains of other dinosaurs suggest that it may have been one of the most common dinosaurs in Europe during the Triassic. However there is an alternative explanation to this.

Most of the known Plateosaurus individuals are known from the fossil sites of Trossingen, Halberstadt and Frick, but they are unusual in that the only dinosaur skeletons known from them are Plateosaurus. The only other remains are indeterminate theropod dinosaur teeth and an individual of the turtle Proganochelys. Study of the locations reveals that in the Triassic the area was covered by large expanses of mud which acted as a mire. Plateosaurus probably came to these areas to feed upon the plants growing in these bog-like conditions, and the most popular consensus is that the larger Plateosaurus occasionally became stuck in the mud. The more they would struggle to free themselves, the more they would get stuck, and eventually exhaustion would cause them to collapse. Theropod dinosaurs of the time were not only lighter but had bigger feet than Plateosaurus which meant that they had a lower ground pressure. This means that they could walk on areas of a bog without sinking in like a large Plateosaurus. Because they were more susceptible to getting stuck, more Plateosaurus got preserved than anything else, but this also explains the current lack of juvenile specimens of Plateosaurus since their lighter builds meant that they could navigate the bogs without getting stuck. Plateosaurus has been reconstructed in many ways over the years, sometimes as a primarily quadrupedal dinosaur, others times only bipedal. For the last few decades now though, Plateosaurus has almost always been depicted as a primarily bipedal dinosaur that walked around on just its hind legs. It was already more heavily built than theropod dinosaurs of the time, and it is not out of the question that it may have rested on all fours when browsing on low vegetation. Later as sauropodomorphs grew bigger and had to accommodate a larger digestive system, they would be forced to walk around on all fours.

The centre of gravity in Plateosaurus would have been roughly where the hips were, which meant that the body weight went straight down the hind legs. Further support for a bipedal stance in Plateosaurus comes from the simple observation that when the forearms are correctly set up the hands are incapable of pronating, which means that they just could not support the body weight properly.

The fingers of Plateosaurus had long claws on them which could have been used for hooking around branches and fronds of vegetation so that they were held steady while an individual fed. Alternatively they may have also been used to defend against predators with an individual swiping them at an attacking predator to try and slash them.

The hind limbs were well adapted for bearing the body weight, but lacked muscles that were capable of providing a ‘spring’. What this means is that when Plateosaurus walked, one of the hind feet had to be touching the ground at all times, and that speed was controlled by altering the stride and changing the speed of leg movement. This would be as close as to running as what Plateosaurus could get, but true running however is defined by an ‘airborne’ phase where the rear foot pushing leaves contact with the ground before the landing foot touches it. However this does not mean to say that Plateosaurus were slow, they would only need to be able to outpace predators to stay safe.

There has been much debate over exactly what sauropodomorph dinosaurs ate since they immediately evolved from meat eating ancestors, and would eventually have exclusively plant eating descendants. Plateosaurus however were almost certainly herbivorous, this can be seen just from looking at the teeth and skull. The teeth of Plateosaurus are broad and leaf shaped, not the pointed triangular teeth of a predatory theropod. The skull is also adapted for a strong bite which means that in all probability the jaw muscles combined with the teeth for processing plants by slicing and mashing. This could also denote a preference for tougher plants or processing them in the mouth because they lacked a large enough digestive system to break down the plants by processes such as fermentation. Later sauropods with larger digestive systems would basically just gulp down mouthfuls of plants with little to no processing taking place in the mouth. Gastroliths (stones) are known to have been swallowed by some dinosaurs, and some that you might not expect such as the theropod Lourinhanosaurus. No gastroliths have ever been found in association with Plateosaurus however, and given that members of the genus could process food in their mouths, it is very unlikely that they made use of them.

One of the most startling revelations about Plateosaurus is that it seems to have had an avian-like (bird-like) respiratory system. This was originally indicated by analysis of the growth patterns in the bones, but new studies of the anterior portion of the post cranial skeleton now reveal that in life Plateosaurus would have had a system of air sacs similar to how birds do today. The presence of such a respiratory system has long been suspected for later sauropod dinosaurs and is part of the explanation for how they could lift their necks, because if they were filled with a network of air sacs they would have been far lighter than if they were just solid tissue.

To fully appreciate how the presence of an avian-like respiration system present in Plateosaurus can affect our wider understanding of dinosaurs and evolutionary theory, you need to bear in mind that birds evolved from the theropod line of dinosaurs, not the sauropods. This leaves us two possibilities, the mundane of which is that an avian-like respiratory system evolved twice, once in the sauropodomorphs, and again in the theropods. An alternative and much more exciting possibility however is that the avian system goes back further than Plateosaurus, all the way to the very first dinosaurs before they had split into the theropod and sauropodomorph groups.

The presence of an avian-like respiratory system also yields a further possibility for dinosaur biology; that all dinosaurs were indeed endothermic. This means that much of their body heat was produced by internal body processes and that they were not reliant upon heat from the surrounding environment to survive like more primitive reptiles like lizards were. In simpler terms, dinosaurs were more like warm-blooded animals than cold-blooded ones.

Further support for an endothermic metabolism comes from study of the growth patterns of the bones. Like with all other known dinosaurs, Plateosaurus experienced the fastest rate of growth when juvenile, before slowing down in later life. The scleral rings of Plateosaurus also indicate that individuals would be active for short periods both during the day and night times. Such variation also suggests an endothermic metabolism since they would not be restricted to feeding only during certain parts of the day.

Because so many individuals are known, and study of the growth stages of individuals is possible, palaeontologists can even determine the age range for Plateosaurus. Most known individuals are between 12 and 20 years old, and further to this, Plateosaurus seemed to have reached adult size by 12 years of age. Plateosaurus however did not stop growing here, they just continued at a slower rate. While the average age of Plateosaurus seems to have been 12 to 20 years, remains of one individual known to have reached 27 have been studied. It also needs to be appreciated that the average age of 12-20 years may be skewed because it is based upon individuals that died after getting stuck in mud rather than dying from old age. At the time of writing the youngest Plateosaurus individual known was 10 years old when it died.

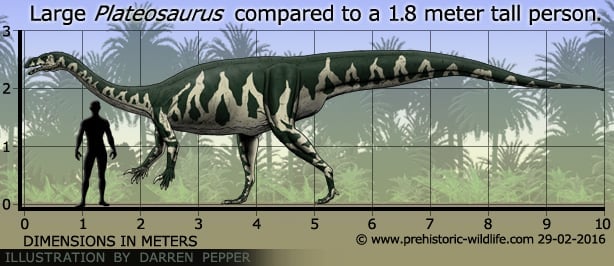

One thing that is unusual for Plateosaurus and is not commonly seen in dinosaurs is that adult size between individuals can vary greatly. Termed developmental plasticity, some individuals of Plateosaurus were only 4.8 meters long when then reached adulthood, while others comfortably reached 10 meters long. The reasons for this great variation are not fully known, but it could be that times of food shortages meant that there was less available energy to devote towards growth, therefore individuals living in these times became stunted. By contrast, individual Plateosaurus living in times of plenty had more energy for growth and so became bigger. This may be an inherent survival mechanism where rather than starving and becoming extinct, the genus simply adapted to changing food availability so that they did not grow beyond a point where they could not support themselves. Such dwarfism is often seen in animal populations that find themselves on islands cut off from the mainland and then grow physically smaller to adapt to the reduced food resources.

There is no clear indication to suggest that Plateosaurus lived in herds, but then there is also no indication to suggest they didn’t. Large numbers of Plateosaurus discovered in what were muddy bogs have been interpreted as whole herds that became trapped in a mudflow, while alternative explanations propose that the large numbers of Plateosaurus exist because they were more common. But as a herbivore, there is a chance that Plateosaurus may have travelled around in loose herds, or at the very least congregated together because of food availability. Herbivores sticking around together also have a higher chance of survival because they are more likely to spot threats like roaming predators.

Plateosaurus would have been one of the main herbivorous dinosaurs present in Europe at the end of the Cretaceous, and as such it was likely a commonly targeted prey species. Early theropod dinosaurs would have been an obvious threat, and discoveries of saurischian dinosaurs like the South American Herrerasaurus prove that these kinds of dinosaurs were already growing to sizes that could threaten sauropodomorphs like Plateosaurus. Other threats present also include archosaurs like Smok, that while possibly slower than dinosaurs like Plateosaurus, could have still hunted them by ambush tactics.

Further Reading

- Die fossile Reptil-Ordnung Saurischia, ihre Entwicklung und Geschichte” [The fossil order of reptiles Saurischia, their development and history], F. von Huene - 1932. - Cranial anatomy of the prosauropod dinosaur Plateosaurus from the Knollenmergel (Middle Keuper, Upper Triassic) of Germany. I. Two complete skulls from Trossingen/W�rtt. With comments on the diet, Peter M. Galton - 1984. - Late Triassic continental vertebrates and depositional environments of the Fleming Fjord Formation, Jameson Land, East Greenland, F. A. Jenkins Jr., N. H. Shubin, W. W. Amaral, S. M. Gatesy, C. R. Schaff, L. B. Clemmensen, W. R. Downs, A. R. Davidson, N. Bonde, F. Osbaeck - 1994. - Were the basal sauropodomorph dinosaurs Plateosaurus and Massospondylus habitual quadrupeds?”, in Barrett, P.M.; Batten, D.J., Evolution and Palaeobiology of Early Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs (Special Papers in Palaeontology 77), Matthew Bonnan & Phil Senter - 2007. - The Norian Plateosaurus bonebeds of central Europe and their taphonomy, P. M. Sander - 1992. - Redescription of a nearly complete skull of Plateosaurus (Dinosauria: Sauropodomorpha) from the Late Triassic of Trossingen (Germany), A. Prieto-M�rquez & mark A. Norell - 2011. - Prosauropod dinosaurs from the Feuerletten (Middle Norian) of Ellingen near Weissenburg in Bavaria. In “Second Georges Cuvier Symposium, Montbeliard (France), P. Wellnhofer - 1994. - Prosauropod dinosaurs and iguanas: Speculations on the diets of extinct reptiles, paul M. Barrett - 2000. - Prosauropod dinosaur Plateosaurus (=Gresslyosaurus) (Saurischia: Sauropodomorpha) from the Upper Triassic of Switzerland, Peter M. galton - 1986. - The prosauropod dinosaur Plateosaurus Meyer, 1837 (Saurischia: Sauropodomorpha; Upper Triassic). II. Notes on the referred species, Peter M. Galton - 2001. - The digital Plateosaurus II: an assessment of the range of motion of the limbs and vertebral column and of previous reconstructions using a digital skeletal mount, H. Mallison - 2010. - Nocturnality in dinosaurs inferred from scleral ring and orbit morphology, L. Schmitz & R. Motani - 2011. - What pneumaticity tells us about ‘prosauropods’, and vice versa, M. J. Wedel - 2007. - The early evolution of postcranial skeletal pneumaticity in sauropodomorph dinosaurs, A. M. Yates, M. J. Wedel & M. F. Bonnan - 2011. - A revision of the problematic sauropodomorph dinosaurs from Manchester, Connecticut and the status of Anchisaurus Marsh, A. M. Yates - 2010. - Developmental plasticity in the life history of a prosauropod dinosaur, M. Sander & N. Klein - 2005.