In Depth

Prognathodon was a late mosasaur that showed a trend towards a different kind of predation that saw it living like the much earlier basal placodont reptiles of the Triassic such as Placodus. This means that Prognathodon specialised in eating tough shelled prey items like shellfish, ammonites and turtles. The diet of Prognathodon was for a long time just speculation based upon the teeth and jaw construction, but two discoveries in Canada in the early years of the twenty-first century not only revealed the full body shape of Prognathodon but the diet as well. One specimen revealed the presence of turtle and ammonite fossils located where its stomach would have been. Interestingly it also had a one-hundred and sixty centimetre long fish in its gut, suggesting that while Prognathodon was a specialised predator, it was also opportunistic in its feeding.

Prognathodon had a robust and heavy jaw that would have been capable of withstanding a high bite force supplied by powerful jaw muscles. However it’s the teeth that should receive special note as not only are they strong and well adapted for crushing, they have serrations which can be seen under much more detailed inspection. This makes the teeth specialised for a dual purpose, destroying the protective shells of prey while shearing the flesh within. Another specialisation is the presence of bony rings around the eye sockets. This is seen as a deep water adaptation for the eyes to better withstand the higher water pressure of deep water, something which may have often been necessary when diving for ammonites.

Why Prognathodon shifted towards this kind of diet when mosasaurs are generally perceived to be apex predators of other reptiles and fish remains uncertain. It could have been that competition for the ecological niche of apex predator was so fierce that the only way Prognathodon could evolve and survive was by adapting to a different food source, removing the need for competition with other predators. It could also be that numbers of large prey animals that mosasaurs are traditionally associated with began to fall, necessitating a need to switch to a different diet. It could have course been to simply exploit an abundant food supply. What is certain is that Prognathodon was not the only mosasaur to adjust to this diet with another named Globidens also having particularly large and rounded crushing teeth in its mouth.

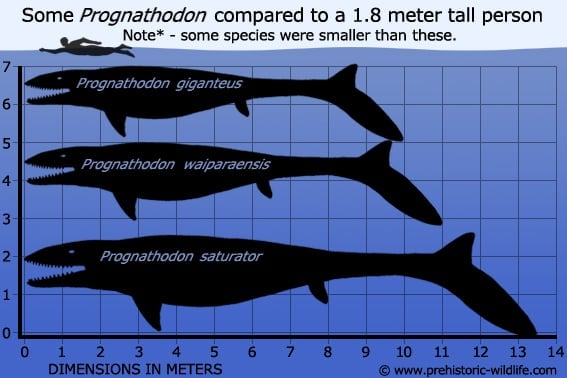

For a time a particularly large specimen of Prognathodon was split off from P. curri into its own genus named Oronosaurus, and a consequence of this resulted in the upper size estimate being reduced to ten metres long. However further study of the material has revealed that the original interpretation was the correct one. Today Oronosaurus is now regarded as a synonym to Prognathodon. The largest species of Prognathodon at the time of writing is P. saturator which has an estimated body length of thirteen meters and seventy centimetres.

2013 saw the description of a Prognathodon specimen first discovered in 2008 which led to the announcement that like with the genus Platecarpus, Prognathodon too had a bi lobed tail. This basically means that the tail of Prognathodon did not just curve downwards but had and additional growth upwards, something quite more advanced than more primitive formed mosasaurs. Although not as well developed as the bi lobed tails of fish and advanced ichthyosaurs, this tail would have still provided extra push against the water meaning more efficient and faster swimming. This probably allowed Prognathodon to dive deeper faster so that it could hunt for prey longer before returning to the surface for air.

Further Reading

– A new species of gigantic mosasaur from the Late Cretaceous of Israel – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22 (3): 629 – P. Christianson, N. Bonde – 2002. – A new species of Prognathodon (Squamata, Mosasauridae) from the Maastrichtian of Angola, and the affinities of the mosasaur genus Liodon – Proceedings of the Second Mosasaur Meeting, edited by M. J. Everhart, Fort Hays Studies, Special Issue number 3, p. 1-12. – A. S. Schulp, M. J. Polcyn, O. Mateus, L. L. Jacobs & M. L. Morias – 2008. – A new species of Prognathodon (Squamata: Mosasauridae) from the Maastrichtian of Harrana. Fossils of the Harrana fauna and the adjacent areas. – H. Kaddumi – 2009. – Another new species of Prognathodon from the Maastrichtian of Harrana. Fossils of the Harrana fauna and the adjacent areas. – H. Kaddumi – 2009. – New exceptional specimens of Prognathodon overtoni (Squamata, Mosasauridae) from the upper Campanian of Alberta, Canada, and the systematics and ecology of the genus. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology vol 31, issue 5 – T. Konishi, D. Brinkman, J. A. Massare & M. W. Caldwell – 2011. – Soft tissue preservation in a fossil marine lizard with a bilobed tail fin. Nature Communications 4. – J. Lindgren, H. F. Kaddumi & M. J. Polcyn – 2013. – Redescription of Prognathodon lutugini (Squamata, Mosasauridae). – Proceedings of the Zoological Institute RAS. 317 (3): 246–261. – D, V. Grigoriev – 2013. – Redescription and phylogenetic assessment of ‘Prognathodon’ stadtmani: implications for Globidensini monophyly and character homology in Mosasaurinae. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology: e1784183. – J. R. Lively – 2020.