In Depth

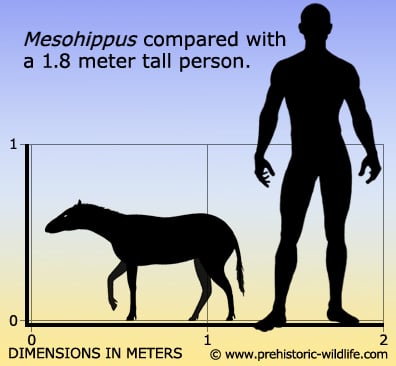

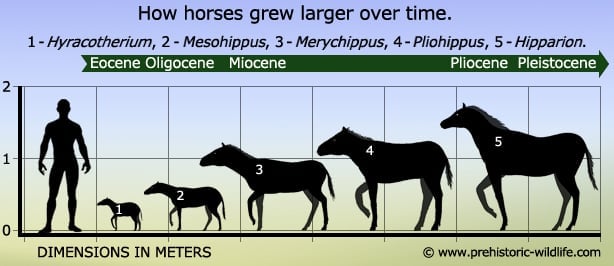

‘Middle horse’ may seem an uninteresting name for a prehistoric horse, but Mesohippus is actually one of the most important. The middle horse name is actually a reference to the position of Mesohippus in relation to earlier forms like Hyracotherium and larger and later forms like we know today. Aside from having longer legs, Mesohippus only had three toes in contact with the ground rather than the four seen in Hyracotherium. The centre toe was the main weight bearing appendage and overall the construction of the foot and larger size reveals that Mesohippus would be the faster horse.

By having longer legs, Mesohippus could cover a greater amount of ground during foraging while expending a reduced amount of energy in doing so. However this adaptation may have also been pushed by the emergence of predators such as Hyaenodon and nimravids (false sabre-toothed cats) that would have been too powerful for Mesohippus to fight. As such the best chance that Mesohippus had of staying alive was to quite literally run for its life and try to outpace and outlast its attacker. Unfortunately for Mesohippus this was not always a successful strategy, with fossils revealing that Mesohippus was a prey animal for the aforementioned Hyaenodon. Despites its position lower down on the food chain however, Mesohippus was the evolutionary success story as its progeny would go on to become larger and faster running horses, while both predators like Hyaenodon and the nimravids would eventually disappear from the planet without any surviving descendants.

Mesohippus was similar to another primitive horse named Anchitherium. In fact one species of Anchitherium, A. celer has been found to be a synonym to Mesohippus bairdi.

Further Reading

– New Oligocene horses. – Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 20(13):167-179. – H. F. Osborn – 1904. – Fossil horses of the Oligocene of the Cypress Hills, Assiniboia. – Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada, series 2 11(4):43-52. – L. M. Lambe – 1905.