In Depth

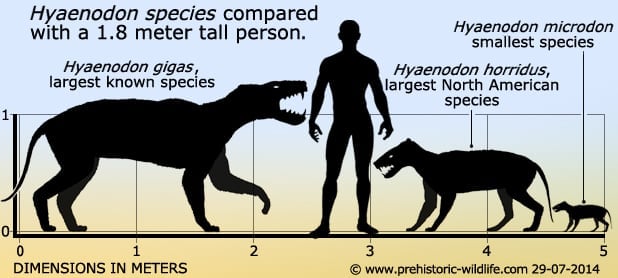

Although Hyaenodon translates as ‘hyena tooth’ the only similarities between Hyaenodon and hyenas are the facts that they are both mammals and they both eat meat. Beyond this they are completely different animals with hyenas being more closely related to cats and Hyaenodon actually being a creodont, a long extinct group of mammals that did not survive the Miocene.

Hyaenodon was the top predator of its day with the larger forms dominating the landscapes throughout the Oligocene periods. Key to this success was the large head that compared to today’s animals looks too large to fit upon the body. Indeed the neural spines of the forward dorsal vertebrae are enlarged to allow for an increased surface are for the attachment of neck muscles powerful enough to support the enlarged skull.

The skull itself has attachments that allow for the fixing of immensely powerful biting muscles would enable the jaws to easily crush prey animals in its mouth. Usually this would involve Hyaenodon biting the head or neck area of the animal. Evidence for this comes from a comparison of predator skulls with the skull of a nimravid called Dinictis which has puncture holes in its cranium that closely match the tooth pattern of Hyaenodon. Additionally coprolites which have been interpreted to belonging to Hyaenodon also have fragmentary parts of other animal skulls in them.

Hyaenodon did not rely upon just crushing animals in its jaws however. Once the prey was down it had to be eaten and for this Hyaenodon had specially adapted slicing teeth at the back of these jaws. The really interesting thing about these teeth is that as the animal grew older these slicing teeth would rotate against each other. This constant grinding against each other meant that Hyaenodon maintained a cutting edge across these teeth for much longer than other carnivores and possibly had a longer life expectancy because of it. This also allowed Hyaenodon to slice meat into smaller pieces rather than gulping down large chunks, something that would allow for faster and more efficient digestion. This is very simply explained by the fact that smaller pieces would result in a larger surface area exposed to the digestive acids in the stomach than would happen if it were a single large piece. A modern analogy would be chemists placing a solid into a solution will almost always use a powdered form of that solid for this very reason.

The slicing teeth that did most of the work in eating where placed at the back of the mouth where they were closer to the point of jaw articulation. This is actually a very common area for the placement of the actual eating teeth because it places them nearer the fulcrum of the jaw mechanism that allows for far more force to be focused through these teeth. This is also why the teeth in the front of your mouth are shaper for biting off a piece of food, while the flatter molar teeth that you use to actually chew your food at nearer the back.

Spending more time processing food in the mouth meant that Hyaenodon would not have been able to breathe through its mouth while it was full with whatever it had just killed. But Hyaenodon had a very simple adaptation to deal with this and this was a bony palate that extended well beyond the back teeth of the upper jaw. This supported the nasal passages so that they continued to carry air to and from the lungs even when the mouth was otherwise blocked.

Out of all its senses, smell seems to have been the most important to Hyaenodon due to CAT scans that reveal a well-developed olfactory bulb. Include the larger skull that would have meant a nasal area with a proportionally larger surface area than a smaller skulled animal, and its reasonable that Hyaenodon tracked prey by scent, possibly identifying which animals were sicker and weaker than the others.

However there is fossil evidence that Hyaenodon did not just randomly roam across the countryside hoping to pick up a scent. A fossil site of what was once a watering hole has been found that contains large numbers of herbivore as well as Hyaenodon remains. While this could be interpreted as Hyaenodon just drinking, predators in other parts of the World such as Africa have been observed to frequent watering holes while hunting for prey. This is simple but also very intelligent behaviour as it is pointless to expend energy on the chance of maybe finding prey some distance from a watering hole, when by staying put you know that your prey will have to eventually come to you in order for the chance to drink.

By being in those locations Hyaenodon would have waited for its target to settle down and drink. With its guard down, Hyaenodon could ambush it from the undergrowth and be upon its prey before it had time to react, with the crushing jaws clamping around its preys head to bring a swift kill. Further fossil evidence for a variety of other animals from small oreodonts, rhinos, camels to even primitive horses like Mesohippus show signs of being fed upon by Hyaenodon which suggests that this predator was not especially selective about what it hunted.

Like with so many of the Cenozoic predators, Hyaenodon seems to have succumbed to the effects of climate change rather than a specific extinction event. As the Miocene period progressed the world’s climate became drier due to global cooling that also resulted in a reduction of sea levels. The result on land was that forests and scrub were being replaced by vast expanses of grassland that many of the herbivores such as the oreodonts were not suited to eating, meaning that the oreodonts that were one of the more common animals disappeared from the menu. Additionally other herbivorous animals were beginning to grow larger with longer legs so that they could better cope with this new kind of environment. As such the types of animals that Hyaenodon used to prey upon like the horses and the camels were becoming too fast for Hyaenodon to catch, with greatly reduced amounts of cover denying Hyaenodon the chance to use ambush tactics to sneak up on prey.

The final occurrence that completed the demise of Hyaenodon was the emergence of new carnivores such as the bear dogs, and while they are more often associated with the old world (such as Asia, Europe, Africa), they were able to spread into North America by crossing the Bering land bridge that was created by the aforementioned falling sea levels. The most famous of this group is Amphicyon, but all of these new predators were more suited to hunting across open ground as well as having larger and more powerful bodies. Hyaenodon could not compete with these new hunters and was quickly relegated to a subordinate position to them. No longer being able to kill its own food, or even scavenge the kills of the more powerful bear dogs, meant that by this stage Hyaenodon was living upon borrowed time.

Further Reading

– Review of the Miocene Wounded Knee faunas of southwestern South Dakota. – Bulletin of the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History, Science 8:165-82. – J. R. Macdonald – 1970. – Paleobiology of North American Hyaenodon (Mammalia, Creodonta). – Contributions to Vertebrate Evolution 1:1-134. – J. S. Mellet – 1997. – Hyaenodon venturae (Hyaenodontidae, Creodonta, Mammalia) from the early Chadronian (latest Eocene) of Wyoming. – American Geological Institute. – Alexander V. Lavrov & Robert J. Emry – 2004. – Hyaenodonts and carnivorans from the early Oligocene to early Miocene of the Xianshuihe Formation, Lanzhou Basin, Gansu Province, China. – Paleontologica Electronica 8(1):1-14. – X. Wang, Z. Qiu & B. Wang – 2005. – Differences in the tooth eruption sequence in Hyaenodon (‘Creodonta’: Mammalia) and implications for the systematics of the genus. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 31(1) – Katharina Bastl, Michael Morlo, Doris Nagel & Elmer Heizmann – 2011. – First evidence of the tooth eruption sequence of the upper jaw in Hyaenodon (Hyaenodontidae, Mammalia) and new information on the ontogenetic development of its dentition. – Pal�ontologische Zeitschrift – Katharina Bastl & Doris Nagel – 2013. – New material on small hyenodons (Hyaenodontinae, Creodonta) from the Paleogene of Mongolia. – Paleontological Journal. 53 (4) – A. V. Lavrov -2019.