In Depth

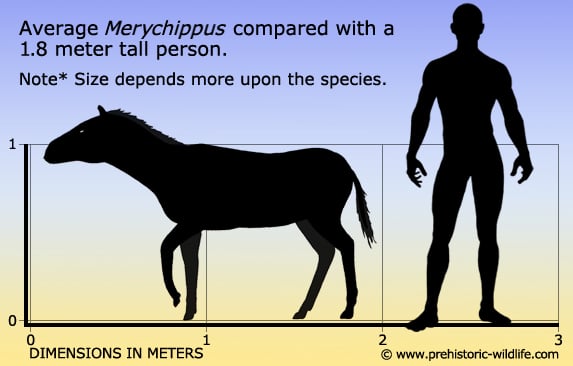

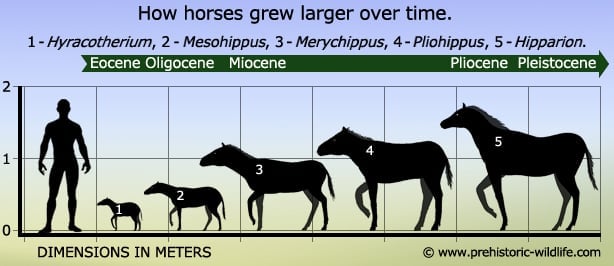

Merychippus is one of the best known occurrences of the appearance of the modern horse form that is much better adapted to running. Whereas the earlier forms such as Hyracotherium and Mesohippus had more than one weight bearing toe, Merychippus supported its body weight with feet that ended with a single well adapted toe that ended in a hoof. Two toes were still present upon either side of this enlarged toe, but they were already reduced to the point of being vestigial (present but not fulfilling any purpose) and in modern horses these cannot be seen at all. The leg muscles had also become more developed and concentrated, with articulation in the lower leg relying more upon the attachment of long tendons that allowed for more spring in its motion.

Merychippus also represents one of the first grazing horses and was able to take much better advantage of the grassy plains ecosystems than its ancestors that were browsers. This dietary adaptation can be established from the observation that the incisors at the front of the mouth were better for cropping off mouthfuls of grass, and the crowns of the molar teeth which ground it together were much higher. These teeth also led to a more developed jaw to house them and cope with the increased grinding motion, leading towards a more recognisable horse-like head shape. Related to the head shape is a larger brain cavity which denotes a higher level of intelligence and/or awareness of its surroundings. A further adaptation to a grazing lifestyle is a proportionately longer neck than its browsing ancestors which allowed Merychippus to more easily reach the ground.

There is some confusion about how Merychippus digested food since its name literally translates as ‘ruminating horse’. An animal than ruminates essentially chews its food before swallowing and passes it into a forward stomach where bacteria break down the food further. It is then later regurgitated back into the mouth in a form we call ‘cud’ where it is chewed further before being swallowed again, this time into the main stomach for full digestion. The problem is that while this method is known in some ungulates (hoofed mammals) like cows, it is completely unknown in horses, and other animals like rhinos and tapirs that horses share a common ancestor with. Unless soft tissue remains, or impressions of them in rock can be found to support this, palaeontologists are of the opinion that Merychippus digested grass by the fermentation method like all other horses are known to do today.

Merychippus marks the continuing shift in horses towards being able to cope with the emerging plains dominated environment of Miocene North America, a change that began at the end of the Eocene period. Aside from the changing landscape, this change towards a faster running body was also driven by the appearance of faster running predators like Amphicyon and Epicyon which were considerably better adapted than earlier creodonts like Hyaenodon. This represents one aspect of an evolutionary arms race where predators have to adapt to catch faster prey, which in turn has to adapt to run even faster to escape the faster predators.

Further Reading

– The evolution of Oligocene horses. In D. R. Prothero and R. M. Schoch (eds.) – The Evolution of Perissodactyls 142-175. – D. R. Prothero & N. Shubin – 1989. – Merychippus (Mammalia, Perissodactyla, Equidae) from the Middle Miocene of state of Oaxaca, southeastern Mexico. – G�obios 39:771-784 – V. M. Bravo-Cuevas & I. Ferrusqu�a-Villafranca – 2006. – Estimating the body mass of extinct ungulates: a study on the use of multiple regression. – Journal of Zoology 270(1):90-101. – M. Mendoza, C. M. Janis & P. Palmqvist – 2006.