In Depth

During the Pleistocene there was an island called Santa Rosae off the southern coast of California between the areas that are today known as Point Conception and Ventura.

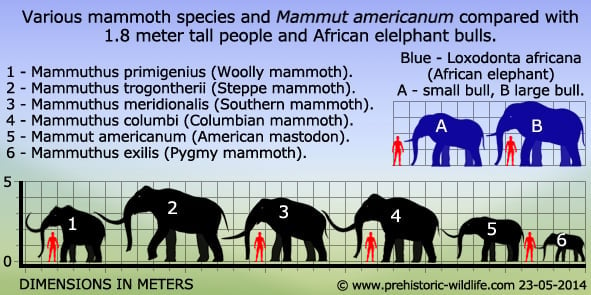

At some point, perhaps when the sea levels were particularly low, Columbian mammoths (M. columbi) crossed over from the mainland to colonise Santa Rosae.

Although large and heavy animals, it’s quite possible that mammoths like their elephant cousins were actually capable swimmers.

Towards the end of the Pleistocene the climate became warmer which caused a rise in sea levels from the melting of the ice sheets that had previously covered much of the northern hemisphere.

As a low lying island, Santa Rosae began to disappear beneath the waves which saw a reduction in the available space for the mammoths to live upon.

Here is where an interesting but often observed survival mechanism kicked in which saw the mammoths progressively growing smaller over successive generations.

Termed ‘insular dwarfism’, the mammoths could not reduce in numbers to the point where the survival of the population was in danger.

But by growing smaller over each generation, the mammoths would not need so much food to fuel their bodies and so could make do with the limited food resources as Santa Rosae grew smaller and smaller.

This progression towards smaller sizes was also helped by the fact that mainland predators such as Dire wolves, Smilodon and the American lion all seem to have been absent from Santa Rosae.

Eventually the smaller body form became stabilised and the smaller forms are now treated as distinct pygmy or dwarf species called Mammuthus exilis.

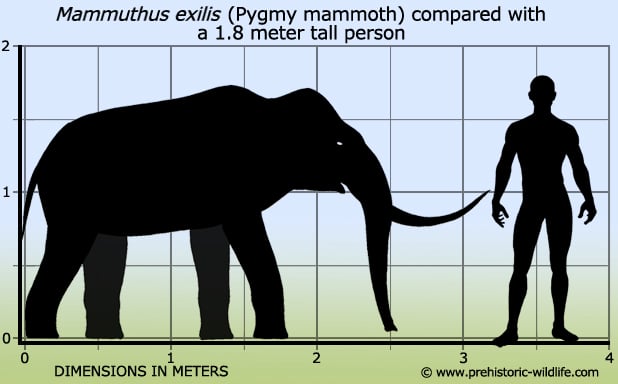

Smaller individuals of M. exilis were as small as one hundred and forty centimetres high at the shoulder, while larger specimens were up to two hundred and ten centimetres high at the shoulder.

This is marked difference from their Columbian mammoth ancestors which are known to have grown well over four meters high at the shoulder.

Today all that remains of Santa Rosae are the Channel Islands of California which are named Anacapa, Santa Cruz, San Miguel and Santa Rosa and with the exception of Anacapa, pygmy mammoth remains have been found on all of these islands.

The disappearance of pygmy mammoths from the fossil record coincides with the arrival of the first people on the Channel Islands which has led to the suggestion that pygmy mammoths were hunted to extinction.

Although plausible, especially for a small population on a limited and isolated land mass, this period also has a marked change in overall climate conditions, and on the mainland at least, it seems that a combination of events was most likely for the disappearance of the North American megafauna as opposed to a single root cause.

Further Reading

- – The Pleistocene elephants of Santa Rosa Island, California. – Science 68 (1754): 140–141. – Chester Stock & E. L. Furlong – 1928.

- – Giant Island/Pygmy Mammoths:The Late Pleistocene Prehistory of Channel Islands National Park. – National Park Service Paleontological Research 4: 35–39. – Larry D. Agenbroad & Don P. Morris – 1999.

- – Mammoths and Humans as Late Pleistocene Contemporaries on Santa Rosa Island. – American Geophysical Union. – L. D. Agenbroad, J. Johnson, D. Morris, T. W. Stafford – 2007.

- – Mammuthus exilis from the California Channel Islands: Height, Mass and Geologic Age. – Proceedings of the 7th California Islands Symposium. p. 17. – Larry D. Agenbroad – 2010.

- – Flightless ducks, giant mice and pygmy mammoths: Late Quaternary extinctions on California’s Channel Islands. – World Archaeology 44: 3–20. – T. C. Rick, C. A. Hoffman, T. J. Braje, J. E. Maldonado, T. S. Sillett, K. Danchisko, J. M. Erlandson – 2012.