Classification confusion

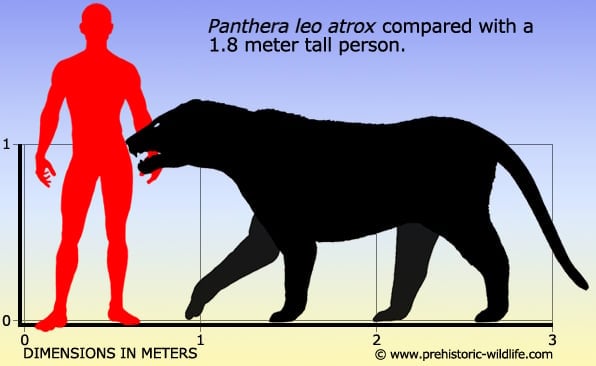

Today the American lion is usually treated as a sub species of the African lion (Panthera leo) which is why it is more commonly credited as Panthera leo atrox.

However there are a large number of researchers who consider the American lion to be different enough from the African lion to give it its own distinct species of Panthera atrox, which is actually the original classification.

However this is just the tip of the iceberg when dealing with the classification of the American lion and it’s easy to become lost amongst the multitude of theories and arguments about its true position amongst other members of the Panthera which includes most modern day big cats.

Early study of the American lion led to it being considered similar to a Jaguar (Panthera onca), and in the mid-1990s it was even considered to be a sub species of tiger (Panthera tigris) based upon similarities to the skull form. The American lion has also been considered to not be a lion at all but a distinct big cat that did not survive into modern times.

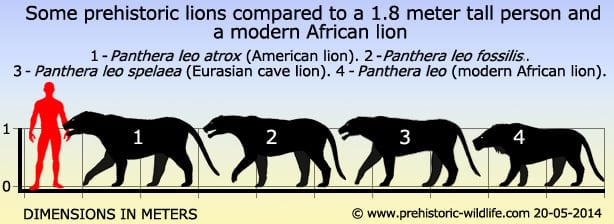

Most palaeontologists however do agree that the American lion is most closely related to the Eurasian cave lion (Panthera spelaea) which is itself is has also been treated as a distinct independent species as well as a sub species of the African lion.

This has been confirmed by mitochondrial DNA analysis which shows that the American lion and Eurasian cave lion were almost identical, although the American does seem to have grown slightly larger.

Current thinking is that Eurasian cave lions crossed over the Bering Strait into North America during the Ionian stage of the Pleistocene only to be cut off from the rest of the world by glacial activity. The resulting small population would have had a limited gene pool where new traits such as growing slightly larger would have been easier to establish, especially if the larger size was of a benefit in the new environment.

A 2016 study (Barnett et al) found that while the American lion is closely related to the modern day African lion, it is genetically different enough to be classed as a distinct species.

Range and ecological role

American lions seem to have been widespread across North America with remains known from Alberta in Canada, past the great lakes to the east coast, all the way back to the Pacific coast in California.

American lions also crossed the Isthmus of Panama to colonise South America, thus taking part in the great American interchange that began during the Pliocene.

This is where animals crossed the land bridge between north and South America to intermix with other animals that were previous isolated. The earlier spread of large North American predators are thought to have been responsible for displacing the phorusrhacid terror birds similar to Kelenken and Phorusrhacos from their positions as top predators from the South American landscape, as they seem to have already disappeared by the time that the American lion reached South America.

African lions can run at high speed but they are not built for prolonged chases, and will often give up the chase if a prey animal quickly outpaces them.

The American lion, although larger than the African still had proportionately short legs that would have enabled it to reach top speed fast, but would have limited its ability to keep pace with longer legged animals like horses which could use their wider striding distance to run even faster.

This means that the only way the American lion could effectively hunt was to use ambush tactics to surprise its prey so that by the time the target realised the danger it was in, the lion was already making its strike.

Like with most predators the American lion probably approached its intended victim from downwind which means the prevailing wind would blow the lions body scent away from the prey so that it did not know the lion was there. Lions like other cats typically squat down low and creep towards they prey while staying in long grasses that conceal the lion’s body, but still allow the lion to see the prey animal because it’s standing above the grass.

Once the lion has gauged that it is close enough it will sprint the final distance leaping onto the back or flanks of the prey trying to knock or wrestle the prey so that it loses its footing and collapses to the floor. Here the lion’s retractable claws come into use to gain extra grip upon the prey. When not used for grappling with prey these claws retract back into the paw so that they are prevented from contacting the ground so that they stay sharp.

Lions will typically use one of two methods to dispatch their prey. First is they may try to clamp their jaws around the throat of the prey and crush the windpipe so that the prey asphyxiates (becomes starved of oxygen which causes it to stop breathing, possibly also triggering cardiac arrest).

The second is what is known as the ‘muzzle clamp’, and like the throat bite this prevents the prey from breathing that leads to asphyxiation, but here the lion closes is jaws around the tip of the snout of the animal. The latter method is often used on prey that manages to stay on its feet despite the lion’s strength.

Pack or solitary hunter?

Although African lions can be seen hunting in groups called ‘prides’ today, it is not certain if the American lion did so as well. In fact evidence from the Rancho La Brea tar pits in California, USA may suggest that the American lion was a solitary hunter.

The tar pits at Rancho La Brea have yielded a wealth of different fossil remains with by far the most numerous being dire wolves and Smilodon (better known as the sabre-toothed cat) while other carnivores like Arctodus (short faced bear) and the American lion are in much smaller quantities by comparison.

Dire wolves almost certainly hunted in packs like their surviving modern day counterparts the grey (Canis lupus), and Arctodus was almost certainly a solitary animal like other bears, both ideas supporting the abundance and lack of their associated remains.

Smilodon also seems to have had a preference for large prey like bison which would have been easier to hunt in groups.

Additionally a 2009 study of African predators (By C. Carbone, T. Maddox, P. J. Funston, M. G. L. Mills, G. F. Grether and B. Van Valkenburgh) played the sounds of animals in distress as if they were stuck in mud out to the surrounding landscape.

The team found that while large animals that hunted in packs had the lowest populations in the ecosystem, they were the most likely to respond to the calls. Individual predators however tended to keep their distance, perhaps to stay out of the way of the larger predators that they knew were coming.

Again this observational data corroborates the expanse of some predators at La Brea, while others are in very small numbers.

While the above idea is plausible, there are a few ideas that counter the theory that American lions were solitary hunters. One is that American lions were not that common with competition from Smilodon among other predators reducing the number of American lions active in Pleistocene California.

It may also be that the American lions in La Brea were individuals that had been kicked out of prides and were left with little choice but to try and scavenge the carcasses in the tar pits. Today, prides of African lions are ruled by a dominant male, but periodically this male will have to fight other roaming males that will challenge the male for control of the pride and right to mate with the females.

It is also worth considering that American lions may have had different behaviour in approaching stuck animals at La Brea with perhaps one lion walking ahead of the others to test the ground.

If the lion made it to the stuck animal and seemed to be okay the others would follow, but if the forward lion became stuck the others would stay back, their core survival instincts holding them back from placing themselves in danger.

Although pure conjecture, this strategy is similar to how in the army one soldier walks point in front of the others as they are advancing. The point guard is usually the first to take enemy fire, but this often allows the main group to take cover and respond.

One final note about the possibility of the American lion hunting in packs is actually associated with the Eurasian cave lion. In Europe cave art left behind by early people depicts the Eurasian cave lion as hunting in groups.

With the American lion considered an off shoot of the Eurasian cave lion, it’s reasonable to infer a greater possibility of this lion hunting in prides.

Further Reading

- – Pleistocene remains of the lion-like cat (Panthera atrox) from the Yukon Territory and northern Alaska – Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 6(5) C. R. Harrington – 1969.

- – Mandibular and dental abnormalities of two Pleistocene American lions (Panthera leo atrox) from Yukon Territory. – B. F. Beebe & T. J. Hulland – 1988.

- – Evolution of the mane and group-living in the lion (Panthera leo): a review – Journal of Zoology Volume 263, Issue 4, pages 329–342. – Nobuyuki Yamaguchi, Alan Cooper, Lars Werdelin & David W. Macdonald – 2004.

- – Phylogeography of lions (Panthera leo ssp.) reveals three distinct taxa and a late Pleistocene reduction in genetic diversity. – Molecular Ecology 18 (8): 1668–1677 – Ross Barnett, Beth Shapiro, Ian Barnes, Simony W. Ho, Joachim Burger, Nobuyuki Yamaguchi, Thomas F. G. Highham, H. Todd Wheeler, Wilfred Rosendahl, Andrei V. Sher, Marina Sotnikova, tatiana Kuznetsova, Gennady F. Baryshnikov, Larry D. Martin, C. Richard Burns & Alan Cooper – 2009.

- – Panthera leo atrox (Mammalia: Carnivora: Felidae) in Chiapas, Mexico. – The Southwestern Naturalist 54 (2): 217–222. – Marisol Montellano-Ballesteros & Gerardo Carbot-Chanona – 2009.

- – Craniomandibular Morphology and Phylogenetic Affinities of Panthera atrox: Implications for the Evolution and Paleobiology of the Lion Lineage. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29 (3): 934–945. – Per Christiansen & John M. Harris – 2009.

- – Phylogenetics of Panthera, including Panthera atrox, based on craniodental characters. – Historical Biology: 1. – L. M. King & S. C. Wallace – 2014.

- – Mitogenomics of the Extinct Cave Lion, Panthera spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810), Resolve its Position within the Panthera Cats. – Open Quaternary. 2: 4. – Ross Barnett, Marie Lisandra Zepeda, Mendoza, André Elias Rodrigues Soares, Simon Y W Ho, Grant Zazula, Nobuyuki Yamaguchi, Beth Shapiro, Irina V Kirillova, Greger Larson, M Thomas & P Gilbert – 2016.

- – The fossil American lion (Panthera atrox) in South America: Palaeobiogeographical implications. – Comptes Rendus Palevol. 16 (8): 850–864. – N. R. Chimento & F. L. Agnolin – 2017.

- – Early Pleistocene origin and extensive intra-species diversity of the extinct cave lion. – Scientific Reports. 10: 12621. – David W. G. Stanton, Federica Alberti, Valery Plotnikov, Semyon Androsov, Semyon Grigoriev, Sergey Fedorov, Pavel Kosintsev, Doris Nagel, Sergey Vartanyan, Ian Barnes, Ross Barnett, Erik Ersmark, Doris Döppes, Mietje Germonpré, Michael Hofreiter, Wilfried Rosendahl, Pontus Skoglund & Love Dalén – 2020.

- – The evolutionary history of extinct and living lions. – PNAS. 117 (20): 10927–10934. – Marc de Manuel, Ross Barnett, Marcela Sandoval-Velasco, Nobuyuki Yamaguchi, Filipe Garrett Vieira, M. Lisandra Zepeda Mendoza, Shiping Liu, Michael D. Martin, Mikkel-Holger S. Sinding, Sarah S. T. Mak, Christian Carře, Shanlin Liu, Chunxue Guo, Jiao Zheng, Grant Zazula, Gennady Baryshnikov, Eduardo Eizirik, Klaus-Peter Koepfli, Warren E. Johnson, Agostinho Antunes, Thomas Sicheritz-Ponten, Shyam Gopalakrishnan, Greger Larson, Huanming Yang, Stephen J. O’Brien, Anders J. Hansen, Guojie Zhang, Tomas Marques-Bonet & M. Thomas P. Gilbert – 2020.