Interactive Mosasaurus Fossil Map & Timeline Chart

Discover Mosasaurus with our interactive fossil map and geographical timeline chart.

The fossil map pinpoints discovery sites worldwide, click each marker to see fossil ages and detailed references..

The interactive bar chart reveals how many Mosasaurus fossils were found across different geological ages, helping you visualize its prehistoric history and global distribution.

Discovery, classification and naming

Like with the dinosaur Megalosaurus, the official naming date for Mosasaurus actually belies its history of study.

Scientific Classification of Mosasaurus

- Squamata (Order)

- Mosasauridae (Family)

- Mosasaurinae (Subfamily)

- Mosasaurini (Tribe)

- Mosasaurus ((Genus))

- Mosasaurini (Tribe)

- Mosasaurinae (Subfamily)

- Mosasauridae (Family)

The first fragmentary skull material was found in the Netherlands in 1764, with subsequent study by Martinus van Marum concluding that the remains were those of a fish (To be fair to him no one at the time knew of the prior existence of giant marine reptiles).

In the early 1770‘s a canon named Theodorus Joannes Godding found a second incomplete skull.

It was a retired army physician named Johann Leonard Hoffmann however that would raise the profile of the creature with his discovery of further remains and correspondence with scientists about them.

The true nature of the creature still remained elusive however as Hoffman thought he had the remains of a crocodile, and even the Dutch professor Petrus Camper also misidentified them as an ancient sperm whale in 1786.

Still it is quite easy to understand where Camper was coming from as even today these remains can be taken as bearing a superficial resemblance to toothed whales like Acrophyseter.

The fossils also form a part of French revolutionary history in that French forces seized them from the Fortress of Maastricht in the Netherlands where they were then transported to France.

An additional bit of trivia: the Maastrichtian age of the Cretaceous (which Mosasaurus is known from) is named after the Maastricht region.

The story of how the remains were captured and the resulting legal challenges in the later years of the eighteenth century is often mentioned but exact details are hard to verify, and the story seems to have developed through a combination of ideas about what happened coming together to form a sequence of events that may not have happened exactly as told.

When the fossils were in France they were studied by Barth�lemy Faujas de Saint-Fond, who also thought the earlier crocodile identification was the correct one.

Study of them continued elsewhere however when Petrus Camper’s son, Adriaan Gilles Camper reviewed his father’s original notes.

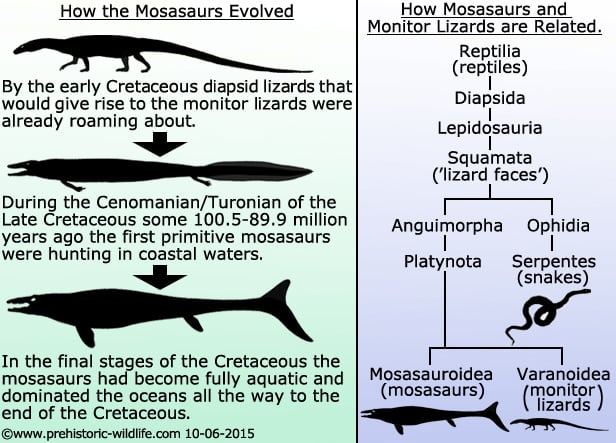

Adriaan Camper disagreed with both the crocodile and whale hypothesis and thought the remains were those of a giant monitor lizard.

Although not quite on the mark, he was still pretty close as monitor lizards are members of the diapsid group of reptiles, the earliest members of which are thought to be the ancestors of the marine reptiles that included the later mosasaurs.

Other later finds such as the 2005 discovery of Dallasaurus lend further weight to the idea that mosasaurs evolved from monitor lizards.

Confirmation for this idea came in 1808 when Georges Cuvier, a leading naturalist who used comparative anatomy to identify unknown bones also agreed with the analysis.

William Daniel Conybeare formerly named the creature Mosasaurus in 1822 with the second skull used for the holotype.

However Conybeare only came up with the genus name, something that happened surprisingly often in the early years of palaeontology.

Mosasaurus did not get a specific type species name until 1829 when Gideon Mantell provided one (something that he also had to do for the first known dinosaur Megalosaurus).

Despite the advancement in its identification, the suggestion that Mosasaurus was an aquatic creature did not happen until 1854 when Hermann Schlegel proposed that the limbs of Mosasaurus where flippers, not feet.

Mosasaurus the marine reptile

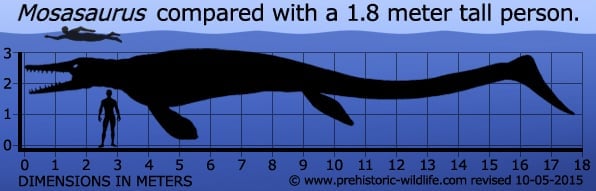

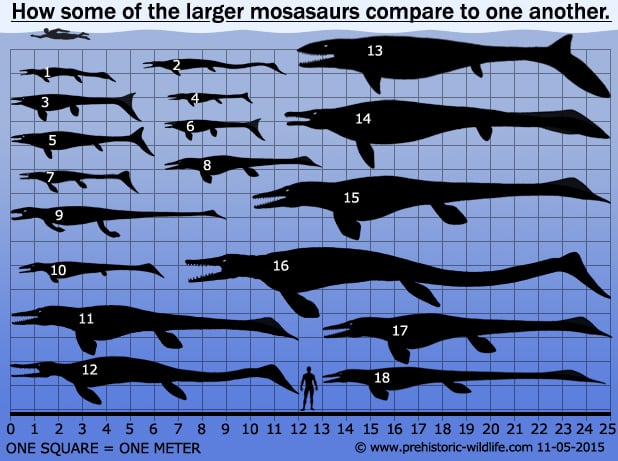

Although probably not quite as long as some of the larger mosasaurs, Mosasaurus seems to have been one of the more heavily built.

In fact Mosasaurus was so robust that a skull discovered in 1998 was mistakenly classed as belonging to Prognathodon, a mosasaur that specialised in eating armoured prey.

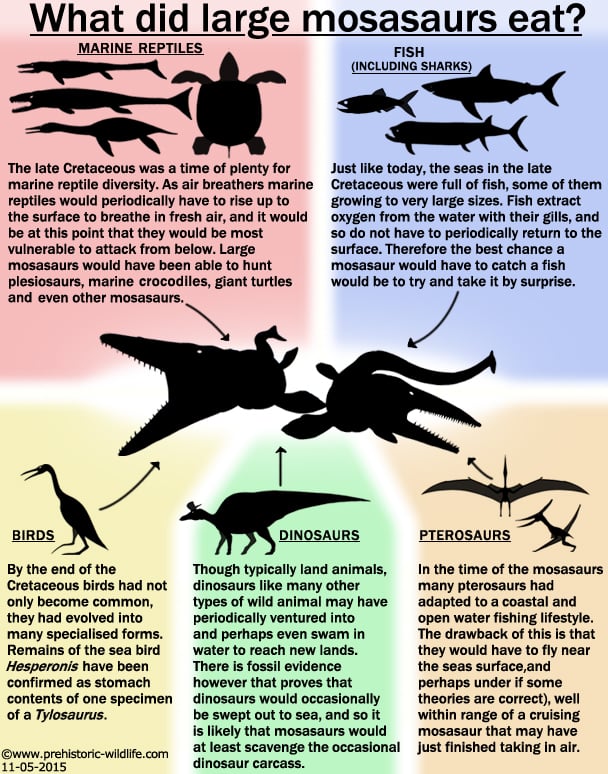

Being such a large creature with a heavy build suggests that Mosasaurus had a preference for larger slower prey, quite probably other marine reptiles.

Further support for this specialisation and behaviour comes from the side wards facing eyes that meant Mosasaurus had poor stereoscopic vision.

A lack of this ability strongly suggests that Mosasaurus did not rely heavily upon gauging distances between itself and prey and as such probably did not rely upon speed to chase down prey over distance.

While some would envision Mosasaurus as a scavenger the fossil evidence also contradicts this as the olfactory bulb (the part that processes smells) is one of the most poorly developed areas. While many oceanic predators use smell to detect injured prey for an easy meal,

Mosasaurus would have been at a disadvantage to most of these. Perhaps the most likely scenario for Mosasaurus hunting behaviour is one that saw it hanging around the upper ocean and waiting for other marine reptiles to surface for air.

At this time they would be at their most vulnerable as they would be in the most lit portion of the water (and silhouetted against the light if Mosasaurus was looking up from below), and unable to dive back down as they would drown without a fresh supply of air in their body.

Using its tail to provide a quick burst of speed Mosasaurus could launch a sudden attack that if it did not kill the prey, would at least injure it so that Mosasaurus could follow and hound it until it tired.

By being a predator of the upper ocean Mosasaurus probably did not have much cause to dive deep.

However the optimum angle of approach for an ocean predator is from below as not only does this make prey easier to spot against the surface light, the murk of the deeper water can conceal some if not all of the body of the hunter until it is ready to strike.

This does not mean descending into the abyssal zone (the part of the ocean so deep sunlight can’t penetrate) as the effect of an animal beginning to disappear into the depths can be seen after just a few meters down.

Mosasaurus probably never had to go further than the maximum depth that its prey commonly frequented which realistically was probably near the surface as well as this provides the greatest abundance of large scale prey species like fish.

It also should be remembered that Mosasaurus is best associated with Europe, much of which was submerged under a shallow sea during the Cretaceous.

Such a marine environment would have made permanent deep water living physically impossible as the depth was just not there.

Mosasaurus has suffered from the wastebasket taxon effect which is where any remains that remotely resemble it automatically get included into the genus.

Over the years a long list of species names has grown as a result, although modern analysis of the remains only recognises the four species above.

Other long held species names are now considered dubious and probably synonymous with other older species.

Further Reading

- – Notes on remains of fossil reptiles discovered by Prof Henry Rogers of Pennsylvania, US, in Greensand Formations of New Jersey. – Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London 5(1):380-383. – Richard Owen – 1849.

- – On the reptilian orders Pythonomorpha and Streptosauria. – Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History 12:250-266. – Edward Drinker Cope – 1869.

- – A new Clidastes from New Jersey. – American Naturalist 15:587-588. – E. D. Cope – 1881.

- – Late Cretaceous marine reptiles of New Zealand. – Records of the Canterbury Museum 9(1):1-111. – S. P. Welles & D. R. Gregg – 1971.

- – Mosasaurus hoffmanni, le ‘Grand Animal fossile des Carri�res de Maestricht’: deux si�cles d’histoire. – Bulletin du Mus�um national d’Histoire naturelle Paris (4) 18 (C4): 569–593. – N. Bardet & J. W. M. Jagt – 1996.

- – Transatlantic latest Cretaceous mosasaurs (Reptilia, Lacertilia) from the Maastrichtian type area and New Jersey. – Geologie en Mijnbouw 78: 281–300 – Eric W. A. Mulder – 1999.

- – Danish mosasaurs. – Netherlands Journal of Geosciences — Geologie en Mijnbouw 84(3): 315-320. – J. Lindgren & J. W. M. Jagt – 2005.

- – Reassessment of Turonian mosasaur material from the ‘Middle Chalk’ (England, U.K.), and the status of Mosasaurus gracilis Owen, 1849. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 34 (5): 1072–1079. – Hallie P. Street & Michael J. Caldwell – 2014.

- – Osteology and taxonomy of Mosasaurus conodon Cope 1881 from the Late Cretaceous of North America. – Netherlands Journal of Geosciences. 94 (1): 39–54. – T. Ikejiri & S. G. Lucas – 2014.

- – A mosasaur from the Maastrichtian Fox Hills Formation of the northern Western Interior Seaway of the United States and the synonymy of Mosasaurus maximus with Mosasaurus hoffmanni (Reptilia: Mosasauridae). – Netherlands Journal of Geosciences. 94 (1): 23–37. – T. L. Harrell Jr. & J. E. Martin – 2014.

- – A small, exquisitely preserved specimen of Mosasaurus missouriensis (Squamata, Mosasauridae) from the upper Campanian of the Bearpaw Formation, western Canada, and the first stomach contents for the genus. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 34 (4): 802–819. – Takuya Konishi, Michael Newbrey & Michael Caldwell – 2014.

- – Rediagnosis and redescription of Mosasaurus hoffmannii (Squamata: Mosasauridae) and an assessment of species assigned to the genus Mosasaurus. – Geological Magazine. 154 (3): 521–557. – Halle P. Street & Michael W. Caldwell – 2017.

- – Dental variability and distinguishability in Mosasaurus lemonnieri (Mosasauridae) from the Campanian and Maastrichtian of Belgium, and implications for taxonomic assessments of mosasaurid dentitions. – Historical Biology. 32 (10): 1–15. – Daniel Madzia – 2019.

- – A new Plotosaurini mosasaur skull from the upper Maastrichtian of Antarctica. Plotosaurini paleogeographic occurrences”. Cretaceous Research. 103 (2019): 104166. – PabloGonz�lez Ruiz, Marta S.Fern�ndez, MarianellaTalevi, Juan M.Leardi & Marcelo A.Reguero – 2019.