In Depth

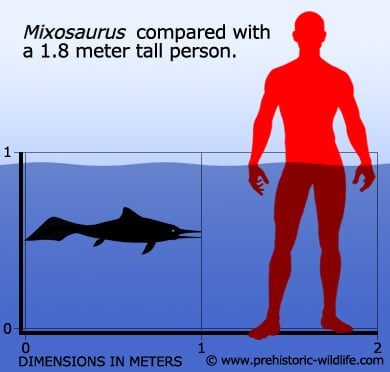

Although very small by ichthyosaur standards, Mixosaurus is one of the most important entries in the fossil record regarding the evolution of the ichthyosaur group of marine reptiles. This is because it is seen as a transitory form between what are termed the eel-like primitive forms like Cymbospondylus and dolphin-like advanced ichthyosaurs like Ichthyosaurus, a mixed combination that has led to a quite obvious name that means ‘mixed lizard’. At a glance this is exhibited by the long slender tail (a primitive trait) combined with a presence of the dorsal fin (advanced trait). Mixosaurus features are also mixed in its paddle-like limbs which are composed of the bones that would have formed all five toes in land animals. This is a primitive feature as later and more advance ichthyosaurs would see the number of ‘toes’ reduced to three. Other key features are the front limbs that reveal Mixosaurus’s path to advanced ichthyosaurs in that the front limbs are longer than those of the rear. This extra size was not the result of the bones already inside the limb growing larger however, but additional bones being added onto the ends of those that already formed the flipper. The development of larger front limbs can actually be taken as an adaptation to a more active and faster swimming lifestyle. This principal is the same for all aquatic creatures that swim by a tail and is particularly noted in fish.

Because the tail pushes rather than pulls the animal through the water it doesn’t counter the weight of the body which means the creature can end up sinking and nose diving into the oceanic depths. To counter this problem the front fins are used like hydroplanes to constantly keep the creature nose level, or at least pointed in the direction that it wants to swim in. The faster an animal like this swims the greater the downwards effect and the larger the front fins need to be to counter it. This can be seen in today’s ocean fauna with some of the fastest swimming fish having some of the proportionately largest pectoral fins. In the case of Mixosaurus these fins could also lead to a proposal of hunting behaviour where Mixosaurus used its newly developed adaptations gain an edge in chasing down more active prey.

The body design of Mixosaurus seems to have been a highly successful one with fossils of Mixosaurus being recovered from all over the world. These widespread fossil sites suggest that Mixosaurus had a cosmopolitan distribution, but all though it seems to have been known all over the world its small size might suggest that it frequented shallow coastal waters over pelagic life in the open ocean. This ecological preference can also be interpreted by looking at the fossil locations. Back in the Triassic the worlds land masses were breaking up but still close together. Both the West coast of North America as well as Asia and Indonesia would have formed parts of the coastlines of the supercontinent once known as Pangaea. The breakup of the continents however also resulted in the creation of new waters with Europe being a shallow sea of island chains, possibly a perfect environment for smaller ichthyosaurs like Mixosaurus.

Mixosaurus has a long taxonomic history which has resulted in many fossil specimens being attributed to it. Closer analysis of some of these fossils has however resulted in the discovery that some of them actually represent similar but different ichthyosaurs. One example is the discovery of Barracudasaurus that was initially thought to have been another Mixosaurus.

Further Reading

– Sui fossili e sull’et� degli schisti bituminosi triasici di Besano in Lombardia. – Atti Della Societ� Italiana di Scienze Naturali 29:15-72 – F. Bassani – 1886. – Eel like swimming in the earliest ichthyosaurs – Nature 382: 347–388. – R. Motani, H. You & C. McGowan – 1996. – Sangiorgiosaurus n. g. – a new mixosaur genus (Mixosauridae, Ichthyosauria) with crushing teeth from the Grenzbitumenzone (Middle Triassic) of Monte San Giorgio (Switzerland, Canton Ticino). – Neues Jahrbuch fur Geologie und Palaontologie Abhandlungen 207(1):125-144 – W. Brinkmann – 1998. – The skull and Taxonomy of Mixosaurus (Ichthyoptergia) – Journal of Paleontology 73: 924–935. – Ryosuke Motani – 1999. – Observations on Triassic ichthyosaurs. Part VIII. A redescription of Phalarodon mahor (von Huene, 1916) and the composition and phylogeny of the Mixosauridae. – Neues Jahrbuch fur Geologie und Palaontologie, Abhandlungen 220(3):431-447 – M. W. Maisch & A. T. Matzke – 2001. – A new mixosaurid ichthyosaur from the Middle Triassic of China. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26(1):60-69 – D. -Y. Jiang, L. Schmitz, W. -C. Hao & Y. -L. Hao – 2006.- A New Look at Ichthyosaur Long Bone Microanatomy and Histology: Implications for Their Adaption to an Aquatic Life. – PLOS ONE. 9 (4): 1–10. – Alexandra Houssaye, Torsten M. Scheyer, Christian Kolb, Valentin Fischer & P. Martin Sander – 2014.