In Depth

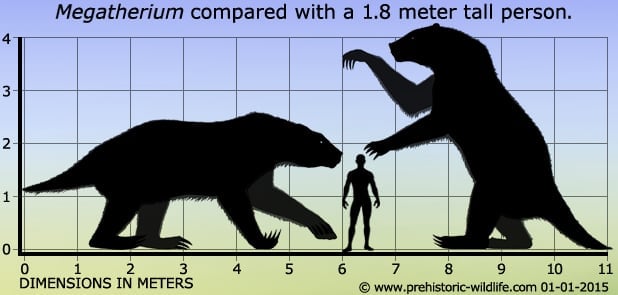

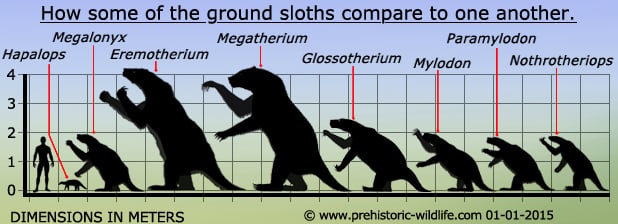

With the possible exception of the woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius), Megatherium is arguably the most famous of the giant mammals that once roamed this planet after the decline of the dinosaurs. Megatherium was also one of the last to disappear with remains appearing in the fossil record until as recently as the start of the Hologene, the period that has seen the rise of mankind and the dawn of civilisation.

Aside from its large size, Megatherium’s skeleton is extremely robust in its construction, and seems to be built not just to support its large body but to provide the maximum amount of stability. The lower bones of the short hind legs are comparable to the femur in thickness and development.

Combined with a short but thick tail and a broad pelvis, the lower body effective becomes a seat for which the upper body can rest on. The price of this lower body development is that Megatherium certainly would not have broken any records for speed, and may have been one of the slowest animals in its ecosystem. However this would not be a problem as Megatherium probably would not have had to run to or from anything.

The upper body construction is along similar lines in its robust build, but has more of a focus upon flexibility. The arms are still built solid and strong for weight bearing, but they are also much longer to provide additional reach.

This reach would have also been increased even further by the large claws on its hands, allowing taller branches and foliage to be brought down to the level of the mouth. The strong jaw is an adaptation more suited for mashing plant material though a combination of strong muscle attachment and robust molar teeth.

The most classic posture that fossil remains and artistic renderings of Megatherium are posed in is of a large shaggy coated sloth that is rearing up on its hind legs.

However, even though Megatherium was certainly capable of shifting its weight to its hind legs, and even walking on just the hind legs as indicated by fossil footprints, Megatherium probably adopted a quadrupedal posture when resting and normally walking extended distances.

Aside from Megatherium’s large body making a quadrupedal posture more stable for weight distribution, the large claws on its hands and feet meant that it had to walk on the sides, and not the flats of its feet.

What did Megatherium eat?

Continuing studies about Megatherium and giant ground sloths in general, have yielded a number of theories as to its diet. One thing which is absolute is that Megatherium would have eaten plants like other giant ground sloths and would have used its large size to reach up into trees to pick out vegetation that was beyond the scope of smaller herbivores.

This meant that competition for food between giant ground sloths like Megatherium and other herbivores was comparatively low, and is one of the reasons why giant ground sloths were able to spread upwards into North America when it became connected to South America during the Pliocene.

Megatherium would have used its ability to walk on just its hind legs to reach further up, where it could use its large claws to pull down branches towards its mouth. Megatherium is also thought to have had a long tongue which it could then use to wrap around the branches, stripping off leaves and soft fresh growth.

However, just because Megatherium could reach up high to feed, it does not mean that it only fed this way. Megatherium would have been quite capable of feeding upon lower vegetation, and here it may have used its claws for digging at plant roots.

The strong teeth and robust jaw suggest that Megatherium was quite capable of chewing tough vegetation, and this adaptation further suggests that Megatherium was capable of adapting to different plant types.

A more controversial theory about Megatherium’s diet is the inclusion of meat. Although generally considered a herbivore, Megatherium has also been portrayed as an occasional scavenger of carcasses, even driving off predators from their kills.

This idea is centred around the theory that Megatherium, and possibly other giant ground sloths, may have needed to supplement their diet with meat in order to obtain nutrients that were lacking in their usual herbivorous diet.

By approaching carcasses they could feed out of opportunity rather than actively aggressing against other animals.

The massive size and power of its body would have also worked in Megatherium’s favour, making it virtually immune to attack from the much smaller predators of the time.

However, some have gone even further than just the scavenger theory and have even suggested that Megatherium could actively hunt and attack other animals if it was so inclined.

The idea for this has been based upon the possibility of Megatherium attacking glyptodonts (armadillo like herbivores such as Doedicurus), flipping them over and then killing them with its claws.

While the mechanics of this scenario are quite easy to imagine, the actual motivation for it has been too much for most palaeontologists to believe. Unless new fossil evidence and/ or new study proves otherwise, Megatherium continues to be regarded as an exclusively, or at the very least primarily herbivorous animal.

Further Reading

- – Nuevos restos de mam�feros f�siles Oligocenos recogidos por el Profesor Pedro Scalabrini y pertenecientes al Museo Provincial de la ciudad del Parana. – Bolet�n de la Academia Nacional de Ciencias de C�rdoba 8:1-205. – F. Ameghino – 1885.

- – Juan Bautista Bru (1740–1799) and the description of the genus Megatherium. – Journal of the History of Biology 21 (1): 147–163. – J. M. L. Pi�ero – 1988.

- – Bipedalism and quadrupedalism in Megatherium: An attempt at biomechanical reconstruction. – Lethaia 29: 87–96. – A. Casinos – 1996.

- – Megatherium, the stabber. – Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 263 (1377): 1725–1729. – R. A. Fari�a & R. E. Blanco – 1996.

- – The smallest and most ancient representative of the genus Megatherium Cuvier, 1796 (Xenarthra, Tardigrada, Megatheriidae), from the Pliocene of the Bolivian Altiplano. – Geodiversitas 23(4):625-645. – P. A. Saint-Andre & G. De Iuliis – 2001.

- – The ground sloth Megatherium americanum: Skull shape, bite forces, and diet. – Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 46 (2): 173–192. – M. S. Bargo – 2001.

- – Mam�feros extintos del Cuaternario de la Provincia del Chaco (Argentina) y su relaci�n con aqu�llos del este de la regi�n pampeana y de Chile. – Revista geol�gica de Chile 31(1):65-87. – A. E. Zurita, A. A. Carlini, G. J. Scillato-Yan� & E. P. Tonni – 2004.

- – A new species of Megatherium (Mammalia: Xenarthra: Megatheriidae) from the Pleistocene of Sacaco and Tres Ventanas, Peru. – Palaeontology 47(3):579-604. – F. Pujos and R. Salas – 2004.

- – Megatherium celendinense sp. nov. from the pleistocene of the Peruvian Andes and the phylogenetic relationships of Megatheriines. – Palaeontology 49(2):285-306. – F. Pujos – 2006.

- – Systematic and taxonomic revision of the Pleistocene ground sloth Megatherium (Pseudomegatherium) tarijense (Xenarthra: Megatheriidae). – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29 (4): 1244. – G. De Iuliis, F. O. Pujos & G. Tito – 2009.

- – Morphology and Function of the Hyoid Apparatus of Xenarthran Fossils (Mammalia). – Journal of Morphology. Vol: 271. Issue: 9, 1119-1133.- L. M. Perez, N. Toledo, G. De Lullis, M. S. bargo & S. F. Vizcaino – 2010.

- – New Pleistocene remains of Megatherium filholi Moreno, 1888 (Mammalia, Xenarthra) from the Pampean Region: Implications for the diversity of Megatheriinae of the Quaternary of South America. – Neues Jahrbuch f�r Geologie und Pal�ontologie – Abhandlungen. 289 (3): 339–348. – Federico L. Agnolin, Nicol�s R. Chimento, Diego Brandoni, Daniel Boh, Denise H. Campo, Mariano Magnussen & Francisco De Cianni – 2018.

- – Campo Laborde: A Late Pleistocene giant ground sloth kill and butchering site in the Pampas. – Science Advances. 5 (3): eaau4546. – Gustavo G. Politis, Pablo G. Messineo, Thomas W. Stafford & Emily L. Lindsey – 2019.