In Depth

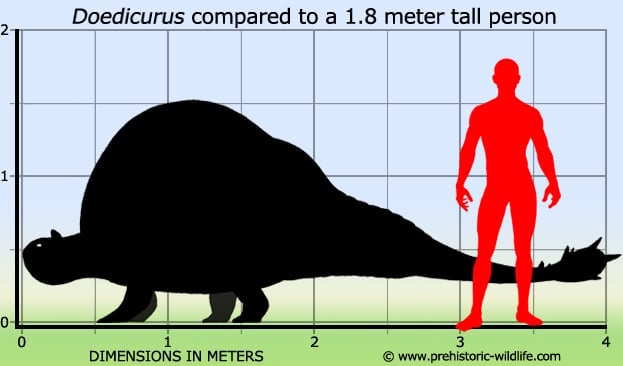

With a length of four meters Doedicurus is easily one of the larger members of the glyptodonts, armoured herbivores that are related to modern day armadillos. Like other glyptodonts, Doedicurus had an armoured shell made from osteoderms that grew to surround its body. This shell was most strongly fixed around the pelvis, with the shoulders retaining a degree of independent mobility while still being covered by the shell. A secondary hump is also present on top of Doedicurus’s back, and this has been suggested by palaeontologists as a fat reserve similar to a camels. While Doedicurus could not withdraw its head into this shell, the head still had bony armour growths that afforded Doedicurus additional protection from predators.

The tail of Doedicurus also had an additional covering of bone that was more flexible than the main shell. The really special adaptation of the tail however was the spiked club on the end, with the flexible armour covering of the upper tail allowing Doedicurus to to swing this club from side to side. It is the removal of these spikes that led to the name Doedicurus, or ‘pestle tail’, as without them, the club seems to be covered in pestles.

The tail club of Doedicurus seems to have been for intra-specific combat between two competing individuals, possibly males looking to attain mating rights over a female. Strong evidence for this behaviour comes from damage on the body shells of some Doedicurus specimens that match the general size and structure of Doedicurus tail club spikes. The scenario would see two Doedicurus squaring off against each other in a side by side head to tail orientation, and then hitting each other in the sides of their bodies with their spiked clubs.

An additional theory for the tail club has been that of predator defence, although when examined in more detail it seems unlikely that a single Doedicurus could have effectively used this club against a predator. The main problem here is that because of the large body shell, Doedicurus could not see behind itself to target an attacking predator. An alternative could be if Doedicurus lived in groups and when attacked clustered facing together and all sweeping their tails in unison to create an intimidating living wall of armour and swinging clubs.

Further Reading

Contributions to a knowledge of the Fossil Vertebrates of Argentina. Part II. 2. The extinct edentates of Argentina. Anales del Museo de La Plata. – Paleontolog�a Argentina 3:1-118 [C. Jaramillo/J. Carrillo] – R. Lydekker – 1894. – Tail blow energy and carapace fractures in a large glyptodont (Mammalia, Xenarthra). – Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society – 126(1): 41–49. – R. McNeill Alexander, R. A. Farin & S. F. Vizca�no – 1999. – The sweet spot of a biological hammer: the centre of percussion of glyptodont (Mammalia: Xenarthra) tail clubs. – Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 276 (1675): 3971–3978. – R. E. Blanco, W. J. Washington & A. Rinderknecht – 2009. – Ancient DNA from the extinct South American giant glyptodont Doedicurus sp. (Xenarthra: Glyptodontidae) reveals that glyptodonts evolved from Eocene armadillos. – Molecular Ecology. 25 (14): 3499–3508. – K. J. Mitchell, A. Scanferla, E. Soibelzon, R. Bonini, J. Ochoa & A. Cooper – 2016. – The phylogenetic affinities of the extinct glyptodonts. – Current Biology. 26 (4): R155–R156. – F. Delsuc, G. C. Gibb, M. Kuch, G. Billet, L. Hautier, J. Southon, J.-M. Rouillard, J. C. Fernicola, S. F. Vizca�no, R. D. E. MacPhee & H. N. Poinar – 2016.