In Depth

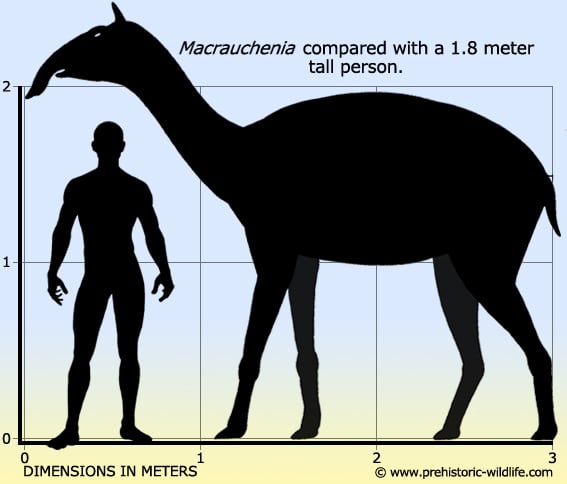

Every now and then in palaeontology an animal comes along that just doesn’t seem like it should have existed at all. Macrauchenia is one such individual creature due to a very bizarre mix body features that have ended up in a mix-match of different creature parts.

To begin first imagine a four legged creature with similar body proportions to a camel, but the first thing you do is lose the hump. The front legs of this creature have short upper portions and long lower portions which indicate a runner. The back legs however have much more developed upper portions and proportionately shorter lower leg areas resulting in back legs that are not suited to fast running at all. At the ends of these legs are feet that are more like what you might expect on a rhinoceros, not especially good for running, but good for traction. A final feature at this point is what could have either been a small trunk or well developed prehensile lip that grew from the tip of the snout like a tapir or elephant. Now consider that as a litoptern Macrauchenia was related to none of these other animals and you are on the tip of the proverbial iceberg in trying to understand this creature.

Fortunately science has helped answer some of the questions about Macrauchenia with carbon isotope analysis of tooth enamel from Macrauchenia teeth revealing that it ate both plants and grasses. This helps clear up the dietary confusion because the prehensile lip/trunk is typically seen as a feeding adaptation stripping leaves from shrubs and low growing trees, whereas the high crown teeth are more indicative of chewing on grasses. The fact that carbon isotopes from both types of plants have been found reveals that Macrauchenia was an opportunistic herbivore that both browsed and grazed, a foraging strategy which could explain its expansion across South America which has been revealed by its broad geographic distribution of remains.

The legs and feet are much harder to explain because of the great difference in form between rear and fore legs. One idea though is that rather than relying upon speed for survival, Macrauchenia might have opted for greater manoeuvrability. This would have been of particular benefit if Macrauchenia lived in areas which had difficult terrain that was hazardous for fast running animals that were not as steady on their feet.

Macrauchenia was one of if not the last of litoptern mammals and may have survived long enough to see the early Holocene period. In the early stages of its existence it would have probably been hunted by South America’s apex predators of the time, the phorusrhacid terror birds. Some of the larger members of this group such as Brontornis, Kelenken and Phorusrhacos itself would have all been capable hunters with the size, reach, power and speed to be a threat to even fully grown Macrauchenia. An additional threat, particularly to smaller juvenile Macrauchenia was the sabre-toothed marsupial Thylacosmilus.

Even with all of these predators however this was still the golden time for Macrauchenia as this was before the event called the Great American interchange. With the creation of the Isthmus of Panama, a permanent land bridge between North and South America, North American animals began to spread into the same habitats as Macrauchenia. Not only were these new herbivores which provided increased competition for existing food resources, but new predators such as proper sabre-toothed cats like Smilodon populator as well as other predators like the dire wolf. Even if Macrauchenia did rely upon manoeuvrability for predator escape, Smilodon likely hunted by ambush and was supremely well adapted for grappling with large and powerful prey. Macrauchenia would have had even less chance dealing with wolves since they hunt by packs and rely more upon forcing their prey to exhaust themselves by overexertion before they go in for the kill. By running around all over trying to evade many predators at once, Macrauchenia would simply make it even easier for the wolves.

As the other litopterns vanished, Macrauchenia held out until the arrival of the first people in South America who also crossed over the Isthmus of Panama towards the end of the Pleistocene. Although early humans often get the blame for wiping out the Pleistocene megafauna like Macrauchenia, this previously ‘catch all’ theory is not as widely accepted as it once was. Climatic shifts during the closing stages of the Pleistocene are now also thought to have been a contributing factor to the demise of much of the megafauna and with Macrauchenia populations already weakened by increased competition, Macrauchenia was even more susceptible to the events of a world changing around it.

Further Reading

– Description of Parts of the Skeleton of Macrauchenia patachonica. – In Darwin, C. R. Fossil Mammalia Part 1 No. 1. The zoology of the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle. London: Smith Elder and Co. – Ricahrd owen – 1838. – Informe preliminar de los progresos del Museo La Plata, durante el primer semestre de 1888. – Boletim del Museo de La Plata II:1-35 – F. P. Moreno – 1888. – Ancient feeding ecology and niche differentiation of Pleistocene mammalian herbivores from Tarija, Bolivia: morphological and isotopic evidence. – Paleobiology (Paleontological Society) 23 (1): 77–100 – B. J. McFadden & B. J. Shockey – 1997. – Ancient collagen reveals evolutionary history of the endemic South American ‘ungulates’. – Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 282. – M. Buckley – 2015. – Ancient proteins resolve the evolutionary history of Darwin’s South American ungulates. – Nature. 522 (7554): 81–84. – F. Welker, M. J. Collins, J. A. Thomas, M. Wadsley, S. Brace, E. Cappellini, S. T. Turvey, M. Reguero, J. N. Gelfo, A. Kramarz, J. Burger, J. Thomas-Oates, D. A. Ashford, P. D. Ashton, K. Rowsell, D. M. Porter, B. Kessler, R. Fischer, C. Baessmann, S. Kasper, J. V. Olsen, P. Kiley, J. A. Elliot, C. D. Kelstrup, V. Mullin, M. Hofreiter, E. Willerslev, J.-J. Hublin, L. Orlando, I. Barnes & R. D. E. MacPhee – 2015. – A mitogenomic timetree for Darwin’s enigmatic South American mammal Macrauchenia patachonica. – Nature Communications. 8: 15951. – M. Westbury, S. Baleka, A. Barlow, S. Hartmann, J. L. A. Paijmans, A. Kramarz, A. M. Forasiepi, M. Bond, J. N. Gelfo, M. A.Reguero, P. L�pez-Mendoza, M. Taglioretti, F. Scaglia, A. Rinderknecht, W. Jones, F. Mena, G. Billet, C. de Muizon, J. L. Aguilar, R. D. E. MacPhee & M. Hofreiter – 2017. – Fantastic beasts and what they ate: Revealing feeding habits and ecological niche of late Quaternary Macraucheniidae from South America. – Quaternary Science Reviews. 231: 106178. – Karoliny de Oliveira, Tha�sa Ara�jo, Alline Rotti, Dimila Moth�, Florent Rivals & Leonardo S. Avilla – 2020.