In Depth

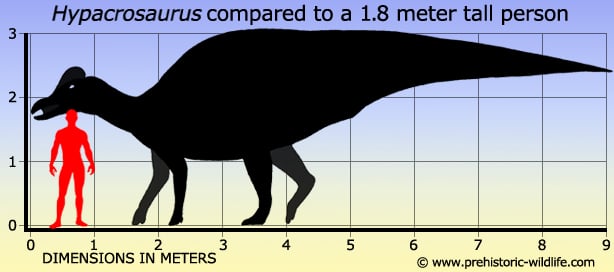

Hypacrosaurus means ‘near the highest lizard’, and in this context the ‘lizard’ was actually the dinosaur Tyrannosaurus, one of the largest dinosaurs in the ecosystems of late Cretaceous North America, but only about a third larger than Hypacrosaurus in the largest individuals (twelve meters for large individual Tyrannosaurus compared to nine meters for Hypacrosaurus). Interestingly Hypacrosaurus and other dinosaurs like it may have actually been prey to Tyrannosaurus and other related genera such as Albertosaurus. Evidence for this comes from a huge bite wound inflicted to the back of an Edmontosaurus that closely matches the shape of a Tyrannosaurus mouth. Because the bones in the wound actually healed afterwards, this proves that the Edmontosaurus in question was alive when it happened, and not a case of a tyrannosaur simply scavenging an existing carcass.

The type species name of H. altispinus is a reference to the tall neural spines of the vertebrae. These tall spines would have significantly increased the height of the body and may have been to facilitate a display function, fat storage for leaner times, to perhaps being to help with activities for swimming (as has been proposed for Magnapaulia). H. stebingeri is significantly important since this is so far made up from the remains of juveniles and eggs that when combined with data from other hadrosaurid genera such as Maiasaura, allows for a serious insight into how these kinds of dinosaurs reproduced and grew up.

Juvenile fossils display growth rings when examined in cross section (similar to what you can see in a tree stump) that indicate Hypacrosaurus achieved reproductive maturity in as little as two to three years while reaching full size in ten. This is significantly faster than in their potential predators the tyrannosaurs. Studies of these dinosaurs show that for the first ten years of a tyrannosaurs life growth would be pretty slow with the individual remaining small. Then in years ten to twenty, growth would rapidly accelerate until the individual reached almost full size and reproductive maturity, before a further ten years of slow and steady growth. To put this in perspective, in the twenty years it took for one generation of Tyrannosaurus to potentially pass, at least six generations of Hypacrosaurus could have happened.

When you compare this to the twenty of so eggs in each Hypacrosaurus nest, you get the conclusion that Hypacrosaurus were breeding at a rate to compensate for high mortality levels. Assuming that environmental conditions were not so much of a factor, this could be because Hypacrosaurus was a viable and common prey species of the time, and tyrannosaurs withstanding, other predators of Hypacrosaurus may have included troodontids like Troodon. These small predators would have been a particular threat to the smaller individuals of Hypacrosaurus, reducing the numbers growing to adult hood.

The crest of Hypacrosaurus is similar to that of its relative Corythosaurus, though wider and not as high. This crest was also hollow which confirms its establishment as a lambeosaurine hadrosaurid (the group typified by Lambeosaurus). Several theories have been made about the function of lambeosaurine head crests, though the one with the most support concerns visual display so that different species of hadrosaur can tell each other apart, probably in a similar fashion to how the differences in the forms of horns and neck frills allow different genera of ceratopsian dinosaurs to be identified.

A theory more specific to lambeosaurine hadrosaurids however concerns the possibility that the hollowness of the crest may in fact be a resonating chamber for amplifying calls. Again the differences in crest form between different lambeosaurine genera could have produced different levels of amplification, and hence different sounding call specific to a distinct species. Although the resonating chamber theory is not supported by all palaeontologists, it is one that is still interesting in itself.

It has already been said that Hypacrosaurus was similar in form to Corythosaurus, but other genera such as Olorotitan and Nipponosaurus are also thought to be closely related.

Further Reading

- A new trachodont dinosaur, Hypacrosaurus, from the Edmonton Cretaceous of Alberta, Barnum Brown - 1913. - On Cheneosaurus tolmanensis, a new genus and species of trachodont dinosaur from the Edmonton Cretaceous of Alberta, Lawrence M. Lambe - 1917. - Taxonomic implications of relative growth in lambeosaurine dinosaurs, Peter Dodson - 1975. - Growth rate of Hypacrosaurus stebingeri as hypothesized from lines of arrested growth and whole femur circumference, L. N. Cooper & J. R . Horner - 1999. - First Evidence of Dinosaurian Secondary Cartilage in the Post-Hatching Skull of Hypacrosaurus stebingeri (Dinosauria, Ornithischia), A. M. Bailleul, B. K. Hall & J. R. Horner - 2012.- Evidence of proteins, chromosomes and chemical markers of DNA in exceptionally preserved dinosaur cartilage. – National Science Review. 7 (4): 815−822. – Alida M Bailleul, Wenxia Zheng, John R Horner, Brian K Hall, Casey M Holliday & Mary H Schweitzer – 2020.