In Depth

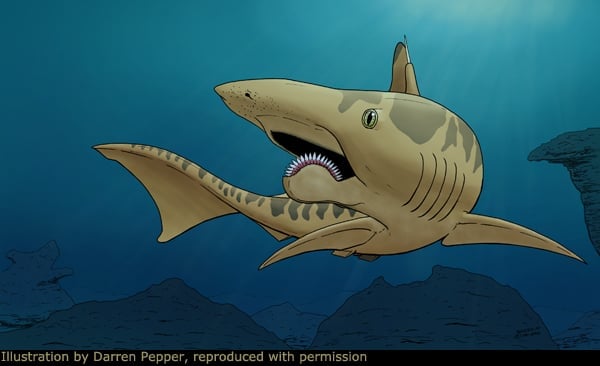

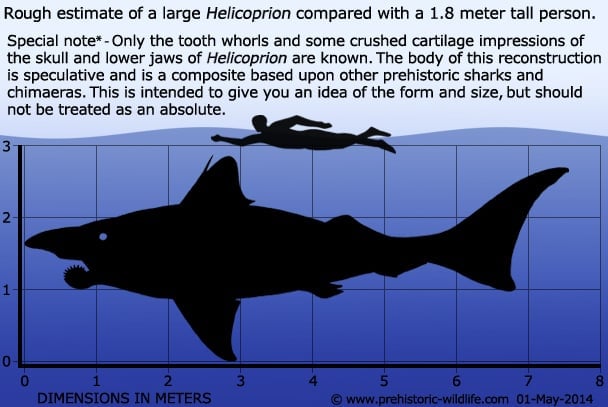

Helicoprion is one of the stranger ‘sharks‘ in the fossil record, although at the time that Helicoprion swam the oceans there were actually many sharks that did not conform to the ‘standard’ form that we know today. The majority of the remains of this shark are the teeth which are fossilised in a spiral pattern like the shell of an ammonite, in fact when first discovered these fossils were actually thought to be some kind of exotic ammonite shell. These arrangements of fossil teeth are today referred to as a ‘tooth-whorl’. How and where the tooth-whorl attached has been a source of puzzlement to palaeoichthyologists ever since it was realised what it was, and while the obvious choice might be to place the tooth-whorl within the mouth, the whorl has on occasion been placed in different parts including the dorsal fin and even the tail. Today the whorl is almost always placed with the lower jaw, though for a long time not everyone agreed with the exact location. If the whorl was mounted on the tip it would significantly increase the drag that Helicoprion experienced as it swam through the water. Not only would it require more effort to swim, the greater water turbulence would have revealed the presence of Helicoprion to its potential prey. This is why many people now consider the whorl to have been further back into the mouth.

Then in 2013 a new study by Tapanila, Pruitt, Pradel, Wilga, Ramsay, Schlader and Didier was published, and this was a watershed moment in the study of Helicorpion as this was the first time that something other than the tooth whorl was studied; crushed cartilage that once formed the head and jaw. Although incomplete, the cartilage which was on a fossil found in Idaho in 1950 and officially described in 1966, was completely revealed by a CT scan which then enabled the researchers to use computer modelling to form a reconstruction of Helicoprion. This study led to a new depiction of Helicoprion with a tooth whorl within a shorter lower jaw. How Helicoprion used its whorl has also been another matter of debate with a variety of theories ranging from the whorl being used as a lash against fish, to a rasp that cut its way through the shells of ammonites with a sawing motion. However even a casual look at the fossil tooth whorls reveals that the teeth have a surprising little amount of wear, and since Helicoprion and relative genera are not thought to have had such a fast replacement of teeth modern day sharks, there is now new speculation that Helicoprion were predators of soft bodied organisms such as molluscs, especially cephalopods such as octopuses.

It may now only be a matter of time before more cartilaginous remains of Helicoprion are discovered, as other creatures with cartilaginous remains from genera such as Cladoselache, Fadenia and Stethacanthus amongst a growing number of many others are being found.

Further Reading

– Ueber die Reste von Edestiden und die neue Gattung Helicoprion. – Verhandlungen der Kaiserlichen Russischen Mineralogischen Gesellschaft zu St. Petersburg, Zweite Series 36:1-111 – A. Karpinsky – 1899. – A new genus and species of fossil shark related to Edestus Leidy. – Science 26(653):22-24 – O. P. Hay – 1907. – Helicoprion ivanovi, n. sp. Bulletin de l’Academie des Sciences de Russie 16:369-378 – A. Karpinsky – 1922. – Helicoprion in the Anthracolithic (Late Paleozoic) of Nevada and California, and its stratigraphic significance. – Journal of Paleontology 13(1):103-114 – Harry E. Wheeler – 1939. – Helicoprion from Elko County, Nevada. – Journal of Paleontology 29 (5): 918–919. – E. R. Larson & J. B. Scott – 1955. – New investigations on Helicoprion from the Phosphoria Formation of South-east Idaho, USA. – Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, Biologiske Skrifter 14(5):1-54 – S. E. Bendix-Almgreen – 1966. – The first record of Helicoprion Karpinsky (Helicoprionidae) from China. – Chinese Science Bulletin 52 (16): 2246–2251. – Xiao-Hong Chen, Long Cheng, Kai-Guo Yin – 2007. – The Orthodonty of Helicoprion. – National Museum of Natural History. Smithsonian Institution. p. 1. – Robert W. Purdy – 2008. – A new specimen of Helicoprion Karpinsky, 1899 from Kazakhstanian Cisurals and a new reconstruction of its tooth whorl position and function. – Acta Zoologica 90: 171–182. – O. A. Lebedev – 2009. – Jaws for a spiral-tooth whorl: CT images reveal novel adaptation and phylogeny in fossil Helicoprion. – Biology Letters 9 (2): 20130057 – L. Tapanila, J. Pruitt, A. Pradel, C. D. Wilga, J. B. Ramsay, R. Schlader & D. A. Didier – 2013. – Unravelling species concepts for the Helicoprion tooth whorl. – Journal of Paleontology. 87 (6): 965–983. – L. Tapanila & J. Pruitt – 2013. – Eating with a saw for a jaw: Functional morphology of the jaws and tooth-whorl in Helicoprion davisii: Jaw and Tooth Function in Helicoprion. – Journal of Morphology. 276 (1): 47–64. – Jason B. Ramsay, Cheryl D. Wilga, Leif Tapanila, Jesse Pruitt, Alan Pradel, Robert Schlader, & Dominique A. Didier – 2014. – Saws, Scissors, and Sharks: Late Paleozoic Experimentation with Symphyseal Dentition. – The Anatomical Record. 303 (2): 363–376. – Leif Tapanila, Jesse Pruitt, Cheryl D. Wilga & Alan Pradel – 2020.