In Depth

Cladoselache is often hailed as the first true shark form to enter the fossil record, and although Cladoselache has a number of features that are different to the sharks that we know today, you can still see a basic fusiform body plan. One thing that makes Cladoselache stand out however is the lack of ‘claspers’. These are two fleshy projections that are present on the underside of modern sharks and serve the purpose of sperm transfer during reproduction. The exact method of reproduction used by Cladoselache is still a matter of debate because no hard evidence exists to show us how it happened. Another thing that separates Cladoselache from other sharks is the overall lack of scales, save for small areas around the mouth, eyes and edges of the fins.

The mouth of Cladoselache was not under slung like in today’s sharks but instead more closely resembled the mouths of other fish. The jaw joint appears to have been quite weak, but was supported by powerful muscles, something that would have enabled Cladoselache to tackle larger prey. The number of gill slits varies between five and seven depending upon the specimen (modern shark forms only have five, with a few late surviving ancient forms having six). The eyes were positioned near the front of the head suggesting that Cladoselache was a visually orientated predator. There were two dorsal fins, also like in modern sharks, with the front dorsal fin being a little bit bigger than the rear one. These dorsal fins were reinforced with fin spines on their front edges to help keep them erect against the flow of water as Cladoselache swam forward. Sharks like the later Hybodus would retain these spikes although they would become quite a bit more developed.

Not only can we see enough to accurately recreate the outside appearance of Cladoselache, but in some fossils the internal workings of the muscles and even some internal organs like the kidneys can also be identified. This has brought valuable insights into the early evolution of sharks with palaeontologists being able to glean some information on their similarity to modern sharks.

The high level of preservation seen in Cladoselache fossils recovered from the Cleveland Shale has even revealed the kind of prey they ate. By far the most popular choice were ray-finned fishes, but Cladoselache also shows signs of being a generalist by also including significant amounts of eel like Conodonts and even arthropods of the extinct Thylacocephala. One specimen of Cladoselache even had the remains of what appear to be another shark inside of it. Cladoselache had an exceptionally streamlined body plan with a broad caudal fin where the epichordal (top) lobe is almost the same size as the hypochordal (bottom) lobe, features that would have provided efficient and fast locomotion through the water. The pectoral fins of Cladoselache were also proportionately large revealing that Cladoselache had to deal with the same problem that sharks do today. Because of their body shape, if the pectoral fins were not present, a shark would nose-dive towards the bottom as it swam. This is why the pectoral fins in sharks act like hydrofoils to counter this effect, and if the fins are proportionately bigger the countering effect is greater. From this it can then be implied that the reasons for this increase in pectoral fin size is to better cope with faster swimming speeds.

These adaptations meant that Cladoselache was a fast and agile predator, a notion that is further supported by the presence of prey that have been preserved inside of Cladoselache fossils. Prey are usually in an orientation that suggests they were swallowed tail first, indicating that Cladoselache actively chased after prey instead of using ambush tactics. The teeth are also adapted for seizing prey instead of slicing through flesh. This is taken from the observation that the teeth are smooth, not sharp, and have the presence of several cusps, or points connected to a single tooth that would have increased the amount of grip Cladoselache had upon its prey. This along with fossil evidence means that prey was swallowed whole.

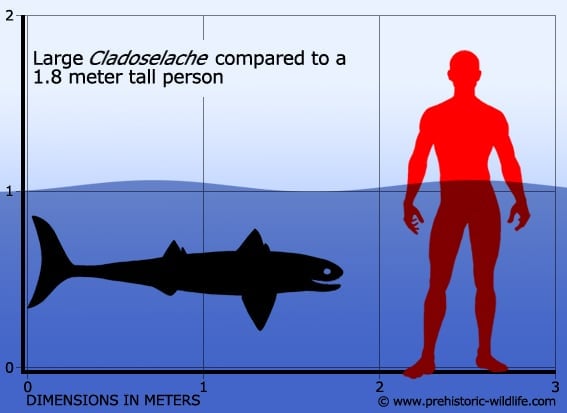

However despite the above adaptations combined with an almost two meter length, Cladoselache was no way near being close to the top of the food chain. That place was reserved by the bony arthrodire placoderms like the ten meter long Dunkleosteus, which were the top predators of the Devonian seas. However Cladoselache had an edge over these potential predators in being both faster and more agile, making it easier for it to stay out of the way.

Further Reading

– Contributions to the morphology of Cladoselache (Cladodus). Journal of Morphology 9:87–114. – B. Dean – 1894. – The dermal tubercles of the Upper Devonian shark Cladosclache. – Annals and Magazine of Natural History 11: 367–368. – A. S. Woodward & E. J. White – 1938. – The paired fins and shoulder girdle in Cladoselache, their morphology and phyletic significance; pp. 111–123 in J. P. Lehman (ed.), Probl�mes Actuels de Pal�ontologie: �volution des Vert�br�s. Colloque international du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 218, Paris. – S. E. Bendix-Almgreen – 1975.