In Depth

The Pliocene and Pleistocene periods are well documented as having a large number of big cats roaming all over the world as apex predators of the landscape, however Homotherium is actually quite different to many of the other genera. To begin with, Homotherium is what is termed a scimitar-toothed cat (after the sword), which means that while it had enlarged upper canine teeth they were not so long that they extended past the lower jaw like they do in sabre-toothed cats like Smilodon. These enlarged canines also had a serrated edge which indicates that they were used for cutting through flesh, although this might be to facilitate killing bites that opened up a wide open wound in prey rather than being feeding tools. Because the teeth were also laterally compressed (as in they were flattened and would look thin when viewed from the front) they were quite weak, and Homotherium would not have taken unnecessary chances with them for fear of breakage.

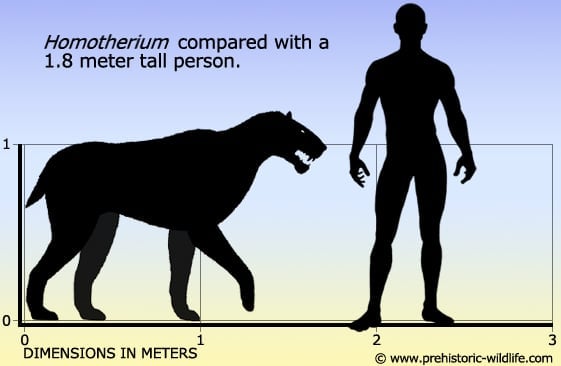

Homotherium is usually associated with higher latitudes like cold steppes which were predominantly colder with large prey animals. One thing that quite literally makes Homotherium stand out as different from other big cats is the shape and proportions of its legs. Homotherium stands tall with especially long fore legs and shoulders that result in its back sloping downwards towards is hindquarters, giving Homotherium a side wards profile similar to that of a hyena (all though it’s fair to bear in mind that hyenas are considered to be closely related to the cats of the Felidae). This means that Homotherium were built for energy efficient travel, and may even have used this advantage to wear prey down in a manner similar to how wolves will constantly harass a prey animal until it collapses with exhaustion. Evidence to support this comes from the enlarged nasal opening that would have allowed for a greater rate of respiration, something that would be necessary for active and energetic hunting.

A further locomotory adaptation seems to be the partially plantigrade feet, which means that Homotherium would have walked with more of the flat of its foot rather than balancing upon its toes. This could be an adaptation to the snowy conditions of the North where Homotherium seems to have been most common, as this would reduce ground pressure from the weight of the body which means that the paws would not have sunk down so much into soft snow, much in the way that snow shoes allow people to walk on snow. This would allow Homotherium extra traction on snowy ground, as well as extra support for dealing with struggling prey.

Homotherium is found in areas that had large amounts of big herbivores like mammoths and rhinos that were suited to open steppe environments. Additionally remains of these herbvivores have been found in association with Homotherium remains, including some deposits that hint towards a specialisation in juvenile mammoths. Large prey like these would be difficult for one individual Homotherium to bring down which supports the theory that Homotherium formed prides similar to modern lions in Africa. This also mirrors behaviour seen in modern lions that will sometimes kill juvenile elephants no more than two to four years old, predatory behaviour that has been both witnessed and documented on film.

Homotherium had both the body and tools to deal with large prey, since the long legs would have also helped it to reach up onto its victim to better use its teeth. The serrations on these teeth could have also allowed them to slice through the preys tough and thick hide to create wounds that bled profusely, weakening the prey until it died from blood loss, perhaps expedited by a bite to neck.

There are collections of juvenile mammoth bones that seem to have been collected by carnivores and hoarded for future consumption, one of the best examples being Friesenhahn cave in Texas, USA where several hundred individual mammoths are associated with the remains of over thirty individual Homotherium. While Homotherium is thought to possibly be one of the predators involved, it is still not known for certain if it was the one doing the hoarding. But if Homotherium was taking body parts from the kill site for later consumption it would infer behaviour that is sometimes seen in modern cats, as well as behaviour of the other key Pleistocene predators such as the cave hyena that was wide spread across Eurasia. Cave hyenas were very similar in body layout to Homotherium, and they seem to have had a preference for killing large prey like woolly rhinos and horses. However cave hyenas were also scavengers, and while most of the remains in their dens were of the aforementioned animals, there are remains for animals that they scavenged. By contrast Homotherium is usually found with mammoths, strongly suggesting that Homotherium was not scavenging them, but hunting them.

It might seem an unnecessary expense of energy for a predator to kill an animal and then carry off large portions of the body away from the kill site, but it actually makes good sense as it helps ensure that the predator that killed the prey gets at least an equal return of energy from feeding from the carcass. Today in Africa leopards are very capable predators, but are small compared to lions, and easily overwhelmed by packs of hyena. To this end they drag their kills up into trees where these other predators cannot follow them, so that they can eat their fill without having it stolen away, or even getting injured in the process. Back in the Pleistocene the rules were no different, Homotherium would have had to hold its own against other big cats like the Eurasian cave lion, cave hyena, wolves, and perhaps most dangerous of all giant bears like Arctodus (better known as the short faced bear) that seem to be best adapted for stealing the kills of other predators. Homotherium, even if hunting in small groups could not fend off these other carnivores indefinitely, and would only be able to eat so much at the first sitting. So by carrying off parts like legs and even heads, Homotherium could have had a chance of a second later feed while abandoning the rest of the carcass to other meat eaters that may have been willing to use force to claim dominance over the carcass.

Like with so many of the Pleistocene predators, Homotherium disappeared completely at a time when much of the other mammalian megafauna that it preyed upon also largely disappeared from the face of the planet. The reasons for this disappearance are still debated, but theories include climate change, human hunting to even diseases spread by new animals migrating into the lands, and of course any combination of the above. The first populations of Homotherium to disappear were in Africa during the early Calabrian stage of the Pleistocene approximately one and a half million years ago. Most of the Eurasian populations however survived to as recently as thirty thousand years ago (late Tarantian) when the landscape was shifting towards a greater coverage of forests that favoured herbivores that Homotherium was not as well suited to hunting.

The very last Homotherium are known from North America and are dated to around ten thousand years ago. Again this coincides with the disappearance of the native megafauna, but also the appearance of the first human settlers that are called Clovis people who are known to have hunted mammoths. There is not sufficient enough evidence to say that human hunting was the sole cause of the disappearance of the megafauna here, but it may well have been a contributing factor in a land that like the rest of the world was experiencing a shift towards a different climate that proved too much for the megafauna to adapt to.

Further Reading

– The saber-toothed cat Dinobastis serus. – Bulletin of the Texas Memorial Museum 2(II), 23–60. – G. E. Meade – 1961. – The scimitar cat Homotherium serum (Cope). – Report of Investigations (Illinois State Museum) (47): pp. 1–80. – V. Rawn-Schatzinger – 1992. – Late Pleistocene survival of the saber-toothed cat Homotherium in northwestern Europe. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 23: 260 – J.W.F. Reumer, L. Rook, K. Van Der Borg, K. Post, D. Mol & J. De Vos – 2003. – Co-existence of scimitar-toothed cats, lions and hominins in the European Pleistocene. Implications of the post-cranial anatomy of Homotherium latidens (Owen) for comparative palaeoecology. – Quaternary Science Reviews 24. -Mauricio Ant�na, Angel Galobart & Alan Turner – 2004. – New saber-toothed cat records (Felidae: Machairodontinae) for the Pleistocene of Venezuela, and the Great American Biotic Interchange – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 31 (2), 468-478 – A. Rinc�n, F. Prevosti & G. Parra – 2011. – New saber-toothed cat records (Felidae: Machairodontinae) for the Pleistocene of Venezuela, and the Great American Biotic Interchange. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 31 (2), 468-478. – Johanna L.A. Paijmans, Ross Barnett, M. Thomas, P. Gilbert, Michael V. Westbury, Axel Barlow & Michael Hofreiter – 2017. – Distinct Predatory Behaviors in Scimitar- and Dirk-Toothed Sabertooth Cats. – Current Biology. 28 (20): 3260–3266.e3. – Borja Figueirido, Stephan Lautenschlager, Alejandro Perez-Ramos & Blaire Van Valkenburgh – 2018.