In Depth

Like its close cousin the American lion (Panthera atrox) the Eurasian cave lion currently has a disputed position amongst other members of the Panthera genus.

Once considered a specific species in its own right the Eurasian cave lion was eventually more widely treated as a sub species of the African lion (Panthera leo).

However, a 2016 study (Barnett et al) and a 2020 study (Stanton et al) has now re-established the European cave lion as a distinct species.

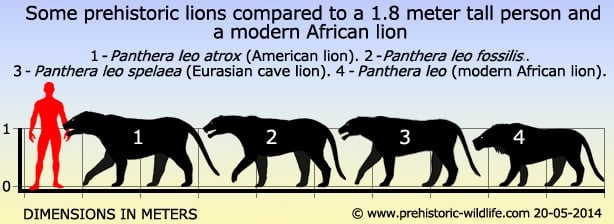

Despite the disputed placement of the Eurasian cave lion, palaeontologists do tend to agree that it evolved from the older Panthera leo fossilis.

Interestingly Panthera leo fossilis was actually larger than the European cave lion (although a touch smaller than the American lion). Usually animals get larger with successive generations unless ecological factors come into play such as reduction of available food or prey for a species.

The Eurasian cave lion got its more common name from the large number of its remains that have been found in caves.

However the result is actually a bit of a misnomer as the Eurasian cave lion is also known from other locations and seems to have been very tolerant of the cold as long as there was sufficient prey to hunt.

However they would also enter caves and its thought that they may have done so to steal away cave bear cubs (Ursus spelaeus) as well as feed on weak hibernating individuals.

Isotope analysis of collagen of the Eurasian cave lion does support the idea that at least some populations regularly ate young cave bears, as well as large amounts of reindeer.

Isotope analysis works upon the principal that herbivorous animals (the cave bear is thought to be primarily herbivorous, occasionally omnivorous) absorb certain isotopes that vary according to what plants they eat, and in turn this isotopes are passed on to the predators that eat them.

Higher amounts of certain isotopes can be corroborated to certain animals indicating a potential prey preference.

This predation may be why so many remains of lions have been found inside caves as inevitably some of the cave bears would fight back, including those woken from their slumber as well as mother bears protecting their cubs.

The Eurasian cave lion was not the only large predator across northern Eurasia with the scimitar-toothed cat Homotherium and the cave hyeana also actively hunting prey. However both Homotherium and Cave hyena were hunters of the open plains that seem to have had a preference for targeting large prey like woolly mammoths and woolly rhinos (such as Coelodonta).

The Eurasian cave lion however seems to have hunted in more densely covered areas like forests which were populated by deer and had increased amounts of cover to allow them to use ambush tactics.

As such while all of these predators were active in these continents at the same time, they operated in different ecosystems which would have reduced competition between them.

While most of the large mammalian predators seem to have disappeared with the sudden absence of large prey at the end of the Pleistocene, it’s harder to be certain about the cave lion. Some evidence suggests that they continued to live in small populations in South-eastern Europe for almost a further ten thousand years, although most of the known remains do not extend past the Pleistocene.

Another argument to suggest late survival is that if reindeer did indeed form a large part of the diet of cave lions, then their prey source did not disappear. Conversely however, the decline in other creatures such as cave bears would suggest that cave lions could have only existed in smaller populations.

Regardless of the actual date that Eurasian cave lions finally disappeared, their final demise probably came about through increased competition with new predators, specifically wolves and early humans.

As the Pleistocene ended, most of the open plains were replaced with forests that the existing megafauna were not adapted to which led to their disappearance. Eurasian cave lions seem to have been at home in this environment so the change should have suited them to become more successful. However wolves were also suited to this habitat, but were previously restricted in their distribution because of the earlier expanse of plains.

No longer facing these barriers they could more easily spread out and hunt the same prey that the cave lions were hunting.

Unless prey is incredibly numerous, no two predators can co-exist by hunting the same prey in the same ecosystem, and eventually one would give. Whereas the Eurasian cave lion was a much larger and more powerful predator, wolves do not require as much food to feed their smaller bodies.

Additionally wolves use completely different hunting tactics to hunt food. Lions hunt by ambush because they cannot outrun a fast animal like a deer in a straight race, they are just not built for it as while their proportionately shorter legs are better at acceleration, their top speed is capped at a lower velocity due to the limits of their leg stride. As such lion hunting behaviour is more about conserving energy, whereas wolves are all about the expenditure of energy.

A pack of wolves will deliberately force a herd of deer to run so that they can pick out the slower and weaker individuals. They will then use their numbers and greater endurance to keep harassing their target until it becomes too weak to go on.

With wolves counting on energetic tactics like this, they could afford to be reckless, and still get a greater gain when they were successful, both advantages that the cave lion did not have.

The third element to this predatory equation is human hunters that also would have been hunting the same animals that both cave lions and wolves were going after. Human hunters had the best advantages of all which included tailor made weapons, the intelligence to use them, and most of all, adaptability to different problems.

The inclusion of cave lions in cave art proves that early humans had contact with them, and just like in Africa today this contact may have at times been a life and death struggle between humans and lions.

In terms of physical ability a lion can easily kill an unarmed person, but when there are several people armed with weapons and working together the lion has no chance.

How much conflict occurred between the Eurasian cave lion and early humans remains a controversial subject as fossil material of both lions and humans together can be interpreted in more than one way.

However early people do seem to have held cave lions in high regard from their inclusion in cave art and like the cave bear, they may have formed a part of early rituals.

It is also thanks to the early humans that we know a little bit more about the life appearance of the Eurasian cave lion that would be impossible to ascertain from just the bones.

These features include the presence of manes in what are presumably males, tufts on the end of the tails and round fluffy ears, the latter likely an adaptation to protect these extremities to the cold conditions.

The art has also been interpreted as having faint stripes running down the body which actually would have been a good adaptation since cave lions would have likely been using trees and shrubs more for cover rather than skulking in long grass like their African relatives.

Additionally cave art has shown several lions hunting together which suggests that the people who created the art observed cave lions hunting in prides.

Further Reading

- The Pleistocene cave lion, Panthera spelaea (Carnivora, Felidae) from Yakutia, Russia. – Cranium 18, 7–24. – G. F. Baryshnikov & G. Boeskorov – 2001.

- Molecular phylogeny of the extinct cave lion Panthera leo spelaea – Molecular Phylogenetics and EvolutionVolume 30, Issue 3 – Joachim Burgera, Wilfried Rosendahl, Odile Loreillea, Helmut Hemmer, Torsten Eriksson, Anders Götherström, Jennifer Hiller, Matthew J. Collins, Timothy Wessg & Kurt W. Alt – 2004.

- Evolution of the mane and group-living in the lion (Panthera leo): a review – Journal of Zoology Volume 263, Issue 4, pages 329–342. – Nobuyuki Yamaguchi, Alan Cooper, Lars Werdelin & David W. Macdonald – 2004.

- Upper Pleistocene Panthera leo spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810) skeleton remains from Praha-Podbaba and other lion finds from loess and river terrace sites in Central Bohemia (Czech Republic). – Bulletin of Geosciences 82 (2) – Cajus G. Diedrich – 2007.

- Phylogeny of the great cats (Felidae: Pantherinae), and the influence of fossil taxa and missing characters. – Cladistics Vol.24, No.6,pp. 977-992 – Per Christiansen – 2008.

- Upper Pleistocene Panthera leo spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810) remains from the Bilstein Caves (Sauerland Karst) and contribution to the steppe lion taphonomy, palaeobiology and sexual dimorphism – Annales de Paléontologie Volume 95, Issue 3 – Cajus G. Diedrich – 2009.

- Phylogeography of lions (Panthera leo ssp.) reveals three distinct taxa and a late Pleistocene reduction in genetic diversity. – Molecular Ecology 18 (8): 1668–1677 – Ross Barnett, Beth Shapiro, Ian Barnes, Simony W. Ho, Joachim Burger, Nobuyuki Yamaguchi, Thomas F. G. Highham, H. Todd Wheeler, Wilfred Rosendahl, Andrei V. Sher, Marina Sotnikova, tatiana Kuznetsova, Gennady F. Baryshnikov, Larry D. Martin, C. Richard Burns & Alan Cooper – 2009.

- Isotopic evidence for dietary ecology of cave lion (Panthera spelaea) in North-Western Europe: Prey choice, competition and implications for extinction. – Quaternary International 245 (2): 249–261. – Hervé Bocherens, Dorothée G. Drucker, Dominique Bonjean, Anne Bridault, Nicholas J. Conard, Christophe Cupillard, Mietje Germonpré, Markus Höneisen, Susanne C. Münzel, Hannes Napierala, Marylène Patou-Mathis, Elisabeth Stephan, Hans-Peter Uerpmann, Reinhard Ziegler – 2011.

- Late Pleistocene steppe lion Panthera leo spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810) footprints and bone records from open air sites in northern Germany – Evidence of hyena-lion antagonism and scavenging in Europe – Quaternary Science Reviews Volume 30, Issues 15–16 – Cajus G. Diedrich – 2011.

- The largest European lion Panthera leo spelaea (Goldfuss 1810) population from the Zoolithen Cave, Germany: specialised cave bear predators of Europe – Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology Volume 23, Issue 2-3 Cajus G. Diedrich – 2011.

- Late Pleistocene steppe lion Panthera leo spelaea (Goldfuss 1810) skeleton remains of the Upper Rhine Valley (SW Germany) and contributions to their sexual dimorphism, taphonomy and habitus – Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology vol 24, issue 1. – Cajus G. Diedrich & Thomas Rathgeber – 2011.

- Palaeopopulations of Late Pleistocene Top Predators in Europe: Ice Age Spotted Hyenas and Steppe Lions in Battle and Competition about Prey. – Paleontology Journal. 2014: 1–34. – C. G. Diedrich – 2014.

- Population Demography and Genetic Diversity in the Pleistocene Cave Lion. – Open Quaternary. 1 (1): Art. 4. – E. Ersmark, L. Orlando, E. Sandoval-Castellanos, I. Barnes, R. Barnett, A. Stuart, A. Lister & L. Dalén – 2015.

- On the discovery of a cave lion from the Malyi Anyui River (Chukotka, Russia). – Quaternary Science Reviews. 117: 135–151. – I. Kirillova, A. V. Tiunov, V. A. Levchenko, O. F. Chernova, V. G. Yudin, F. Bertuch & F. K. Shidlovskiy – 2015.

- Mitogenomics of the Extinct Cave Lion, Panthera spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810), Resolve its Position within the Panthera Cats. – Open Quaternary. 2: 4. – Ross Barnett, Marie Lisandra Zepeda, Mendoza, André Elias Rodrigues Soares, Simon Y W Ho, Grant Zazula, Nobuyuki Yamaguchi, Beth Shapiro, Irina V Kirillova, Greger Larson, M Thomas & P Gilbert – 2016.

- Morphological and genetic identification and isotopic study of the hair of a cave lion (Panthera spelaea Goldfuss, 1810) from the Malyi Anyui River (Chukotka, Russia). – Quaternary Science Reviews. 142: 61–73. – O. F. Chernova, I. V. Kirillova, B. Shapiro, F. K. Shidlovskiy, A. E. R. Soares, V. A. Levchenko & F. Bertuch – 2016.

- Under the Skin of a Lion: Unique Evidence of Upper Paleolithic Exploitation and Use of Cave Lion (Panthera spelaea) from the Lower Gallery of La Garma (Spain). – PLOS ONE. 11 (10): e0163591. – M. Cueto, E. Camarós, P. Castaños, R. Ontañón & P. Arias – 2017.

- Early Pleistocene origin and extensive intra-species diversity of the extinct cave lion. – Scientific Reports. 10: 12621. – David W. G. Stanton, Federica Alberti, Valery Plotnikov, Semyon Androsov, Semyon Grigoriev, Sergey Fedorov, Pavel Kosintsev, Doris Nagel, Sergey Vartanyan, Ian Barnes, Ross Barnett, Erik Ersmark, Doris Döppes, Mietje Germonpré, Michael Hofreiter, Wilfried Rosendahl, Pontus Skoglund & Love Dalén – 2020.