In Depth

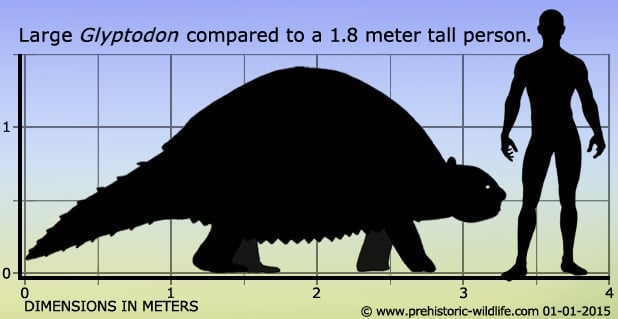

Along with Doedicurus, Glyptodon is one of the better known members of the Glyptodontidae, and as you may have already guessed, is the type genus of this group since this was the first genus to be named. Unlike Doedicurus however, Glyptodon did not possess a spiked club on the end of its tail. Instead Glyptodon had a stubby tail with a rounded end, although as an exposed extremity, it was likely covered with scutes of its own for defence. The presence of Glyptodon in North America as well as South America is proof that this genus took part in the Great American Interchange.

Glyptodon acquired its name (which means carved tooth) from the form of the molar teeth at the back of the mouth, which were also the only teeth present. Glyptodon instead relied upon shearing and pulling plants with the front of its mouth before moving the mouthful back to the rear teeth for processing. Like its relatives, Glyptodon also had a covering of bony armoured scutes that combined to form a protective shell around the body which would have provided quite substantial protection from the teeth of predators that may not have even been able to close their jaws around the shell properly due to the shells immense size.

Glyptodon seems to have gone extinct around eleven thousand years ago, which coincidentally is not long after the very first humans arrived in South America. While the armour of Glyptodon would have provided a powerful blanket defence against most predators, human hunters could use their intelligence to identify weak and vulnerable areas of the body and then use specially crafted tools to strike at them. This hunting is considered to be the most likely cause of the extinction of Glyptodon, though the human hunters of old were anything but wasteful. Aside from eating the meat of the body, the armoured shells of Glyptodon also seem to have been used as shelters by early human settlers.

Further Reading

– Description of a New Specimen of Glyptodon, Recently Acquired by the Royal College of Surgeons of England. – Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 12: 316–326. – Thomas Henry Huxley – 1862. – On the Osteology of the Genus Glyptodon. – Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 1865: The Royal Society Publishing. pp. 31–70. – Thomas H. Huxley – 1865. – Gliptodontes y Cazadores-Recolectores de la Region Pampeana (Argentina) [Glyptodonts and Hunter-Gatherers in the Pampas Region (Argentina)] – Latin American Antiquity 9(2): pp.111-134. – Gustavo G. Politis & Maria A. Gutierrez – 1998. – The diversity of Glyptodontidae (Xenarthra, Cingulata) in the Tarija Valley (Bolivia): systematic, biostratigraphic and paleobiogeographic aspects of a particular assemblage. – Neues Jahrbuch f�r Geologie und Pal�ontologie, Abhandlungen. 251 (2): 225–237. – A. E. Zurita, �. R. Mi�o-Boilini, E. Soibelzon, A. A. Carlini & F. P. R�os – 2009. – Accessory protection structures in Glyptodon Owen (Xenarthra, Cingulata, Glyptodontidae). – Annales de Pal�ontologie. 96 (1): 1–11. – A. E. Zurita, L. H. Soibelzon, E. Soibelzon, G. M. Gasparini, M. M. Cenizo & H. Arzani – 2010. – Evaluating Habitats and Feeding Habits Through Ecomorphological Features in Glyptodonts (Mammalia, Xenarthra). – Ameghiniana: 305–319. – Sergio F. Vizca�no, Guillermo H. Cassini, Juan C. Fernicola & M. Susana Bargo – 2011. – About the occurrence of Glyptodon sp. in the Brazilian intertropical region. – Quaternary International. 305: 206–208. – M. A. T. Dantas, L. M. Franca, M. A. Cozzuol & A. D. Rinc�n – 2013. – A new species of glyptodontine (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Glyptodontidae) from the Quaternary of the Eastern Cordillera, Bolivia: phylogeny and palaeobiogeography. – Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 18 (18): 1543–1566. – Francisco Cuadrelli, Alfredo E. Zurita, Pablo Tori�o, �ngel R. Mi�o-Boilini, Daniel Perea, Carlos A. Luna, David D. Gillette & Omar Medina – 2020.