In Depth

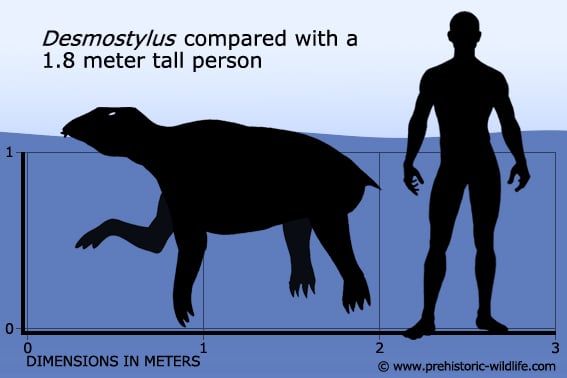

Often described as hippopotamus-like because of its heavily built quadrupedal body, Desmostylus is a peculiar mammal. Palaeontologists are still unsure how Desmostylus is related to other mammals with theories covering a wide range of options from being related to elephants, to hippopotamuses to just being a separate side branch of mammals that left no modern descendants.

Desmostylus is widely believed to have been a semi aquatic animal in that it regularly entered the water, but would return to land to rest. The remains of Desmostylus are known from across most of the northern Pacific Rim from Japan and Russia to the west coast of the United States. This pattern of fossils led to the idea that Desmostylus followed the coastlines to spread out into new territories, however a 2003 study has cast serious doubt upon this. The study in question conducted by Mark T. Clementz, Kathryn A. Hoppe and Paul L. Koch used isotope analysis (of oxygen, carbon and strontium) of tooth enamel from Desmostylus and concluded that it actually lived in freshwater systems. This reveals a picture of Desmostylus living around estuaries and the immediate freshwater systems, however it does not explain the fossil distribution as rivers tend to run into the ocean not run parallel to it. It is perhaps possible that early on Desmostylus was a marine creature that spent more time on the coast, but once a range was established and new mammals such as sirenians (sea cows) began to become more common during the Miocene, Desmostylus were outcompeted and pushed into freshwater ecosystems.

Desmostylus is believed to have fed upon soft aquatic plants that it may have rooted up with its specialised teeth. The anterior lower jaw teeth were also enlarged into tusks and grew into a shovel-shaped arrangement similar to the prehistoric gomphothere elephants (think Gomphotherium). Two more tusk-like teeth grew down from the upper jaw. The back teeth have a cylindrical arrangement which was the inspiration for the name Desmostylus which means ‘chain pillar’ The lower foreleg was also adapted to work best in the water since the bones were fused together to make a rigid appendage. Although this would have been cumbersome on land, since the entire leg would have to be turned to turn the foot, this would have made it easier for Desmostylus to push itself along while in the water.

Further Reading

– Notice of a new fossil sirenian, from California. – American Journal of Science 25 (8): 94–96. – O. C. Marsh – 1888. – Notes on a New Fossil Mammal. – Journal of the College of Science, Imperial University, Tokyo, Japan 16. – S. Yoshiwara & J. Iwasaki – 1902. – Notes on Desmostylus japonicus – S. Tokunaga & C. Iwasaki – 1914. – A review of the Sirenia and Desmostylia. – University of California Publications in Geological Sciences 36 (1): 1–146. – Roy Herbert Reinhart – 1959. – Summary of taxa and morphological adaptations of the Desmostylia. – Island Arc 3 (4): 522–537. – Norihisa Inuzuka, Daryl P. Domning & Clayton E. Ray – 1984. – A paleoecological paradox: the habitat and dietary preferences of the extinct tethythere Desmostylus, inferred from stable isotope analysis. – Paleobiology 29 (4): 506–519. – Mark T. Clementz, Kathryn A. Hoppe, Paul L. Koch – 2003. – Discovery of a desmostylian tooth from Kitami City, northeastern Hokkaido, Japan. – Memoir of the Fukui Prefectural Dinosaur Museum 6: 57–61. – Yukimitsu Tomida & Toshikazu Ohta – 2007. – Habitat preferences of the enigmatic Miocene tethythere Desmostylus and Paleoparadoxia (Desmostylia; Mammalia) inferred from the depositional depth of fossil occurrences in the Northwestern Pacific realm. – Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 471: 254–265 – 2017.