In Depth

In 1965 on July 9th the Polish paleobiologist Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska made what would become marked as one of the most fascinating dinosaur discoveries of all time. During a joint Polish-Mongolian expedition into the Gobi desert of �mn�govi Province, Mongolia, she found the partial remains of a then unknown dinosaur, including a complete pair of forearms with some partially preserved vertebrae and ribs. What made everyone stop and pay attention to this find was that these arms measured about 2.4 meters long, and since these arms were formed in such a way that they seemed to come from a theropod dinosaur, they were the largest dinosaur arms of their kind. Eventually in 1970 these arms were described as the basis for a new dinosaur genus which was named Deinocheirus, which translates to English as ‘terrible hand’, a clear reference to the large size of the hands and claws.

After this Deinocheirus became an established part of dinosaur popularity, with near mandatory inclusion in all dinosaur books along with other big names such as Tyrannosaurus, Diplodocus, Stegosaurus and Triceratops. However in these books the arms were always portrayed as a mystery with statements like ‘no one knows what kind of dinosaur Deinocheirus was’, and these statements persisted into the early days of the internet and into the early twenty-first century. Palaeontologists knew that the arms of Deinocheirus were those of a theropod dinosaur, dinosaurs of the saurischian (lizard hipped) evolutionary line that had well developed rear legs to support bipedal (two legged) locomotion. The large arms were seen as a reflection of a large body size, but they did not match up to the known forms of other large theropod types. A 2006 study by Barsbold and Kobayashi however came to a new conclusion; that the arms of Kobayashi show several characteristics that are akin with the ornithomimosaurs.

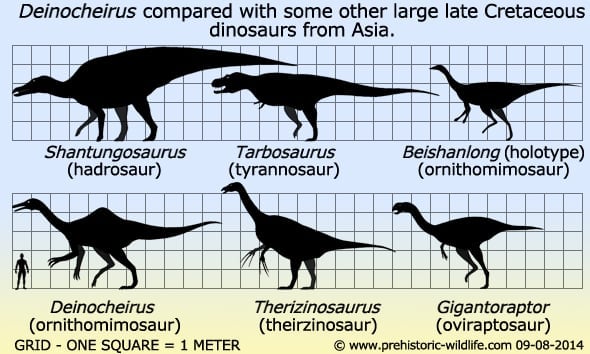

This study raised a few eyebrows, the ornithomimosaurs were theropods, but genera of this group averaged between two and four meters long, with the largest individual genus Gallimimus being up to eight meters long. Even Gallimimus however did not have arms anywhere near as large those of Deinocheirus, which in turn would mean that Deinocheirus would have had to have been the largest known ornithomimosaur and comparable to some of the largest theropods.

Then in 2013, forty-eight years after the first fossils were found in the Gobi desert, two new individuals (discovered in 2006 and 2009) of Deinocheirus were formally presented to the scientific community, and it was confirmed, Deinocheirus was the largest ornithomimosaur. Neither of these individuals was complete, but between them it was possible to get an idea of the complete skeleton. Not only was this the first time that palaeontologists could get a complete idea of what Deinocheirus actually looked like, but the larger of this two individuals actually had arms that were larger than those of the holotype.

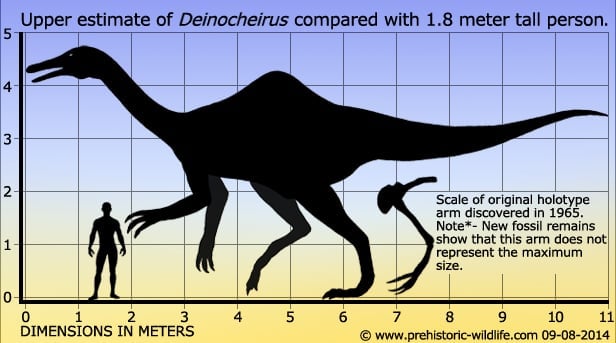

What soured this discovery however is the theft of the skull and feet of these specimens by thieves who stole them so that they could be sold on the fossil black market. Evidently someone or some people were aware of the significance of this find and decided to act to support their own finances as opposed for the good of science. Fortunately at least some of these missing fossils were later found by Francois Eskulie and donated to the Royal Beligian Institute of Natural Sciences. These fossils have now been repatriated to Mongolia with a formal ceremony held on the 1st May, 2014. What we know about Deinocheirus now is that for lack of a better word it was weird. For a start Deinocheirus grew significantly larger than most other ornithomimosaurs, though late cretaceous Asian ornithomimosaurs such as Gallimimus and Beishanlong are both known to have grown up to eight meters long, and these two are also significantly larger than most others. Other types of dinosaurs also seem to have grown unusually large, such as the hadrosaur Shantungosaurus and the oviraptosaur Gigantoraptor. Around 2006 when the second individual of Deinocheirus was found estimates of around ten meters long began to be circulated, but after the 2013 presentation a larger specimen was credited as being as much as eleven meters long.

Whereas Deinocheirus had been famous for the large arms, it is now known that Deinocheirus actually had growths rising up from their backs which may have formed either a heavily built sail or indeed a fatty hump. Once again the same theories regarding the formations of back growths are circulating and this time in reference to Deinocheirus, with the two most common being thermoregulation and fat storage for surviving droughts and times of little food availability. Another is display for interspecies recognition and even signalling members to the opposite sex with a well formed hump indicating a healthy and well fed individual. What is known is that at the time of this discovery, Deinocheirus was the only ornithomimosaur known to have had a growth on its back, something that still stands at the time of writing. In general the diets of ornithomimosaurs are unknown except for a few genera such as Pelecanimimus where we can get a fairly good idea from fossil evidence. Other ornithomimosaurs have been interpreted as being herbivores, predators of small vertebrates like primitive mammals, lizards and snakes, to omnivores that ate both plants and flesh to even egg thieves that raided unguarded nests. When only the arms of Deinocheirus were known, the large claws on the ends of the fingers were interpreted by many to be for rending the flesh of any dinosaur that had been unfortunate to have been caught by them, however we now know that large claws are not always killing weapons.

The wider understanding of therizinosaurs gathered during the latter half of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries is proof that some large clawed theropods were herbivores. This observation coupled with a large concentration of smooth rounded stones discovered near what would have been the digestive area of one of the Deinocheirus specimens, indicating that they may be gastroliths, has been taken as evidence that supports a more herbivorous lifestyle, with the large claws possibly being used to hook around and pull down branches. However, the herbivorous diet theory may not be the only possibility.

With the recovery of the stolen skull, we also know that Deinocheirus had a ‘spoonbill’, upper and lower jaws that widened out to form a rounded spoon-shape. This begs the question, was Deinocheirus similar to modern spoonbill birds that are known to snatch out invertebrates and small fish from water systems. Here the widened bill increases the catch area making it easy to snatch prey from the water. A comparison to the spinosaurs could also be in order. Some genera of spinosaur such as Ichthyovenator and of course Spinosaurus itself are known to have had growths on their backs as well as well-developed and long arms and claws, both features that can now be seen in Deinocheirus. In addition, the possible gastroliths of Deinocheirus could have just as easily have been used to strip off the scales from fish making them easier to digest. It may be that Deinocheirus waited for seasonal rains to swell rivers and water systems which then brought in a greater amount and variety of fish, which they then gorged themselves upon in times of plenty to build up there fat reserves stored in a hump, which they then relied upon to see them through the remainder of the year in leaner times. If true then Deinocheirus may have been in a comparative evolutionary niche as the spinosaurs that were common in earlier in the Cretaceous. Finally one should consider that as a saurischian theropod, Deinocheirus as an ornithomimosaur would have been descended from predatory ancestors and even some earlier ornithomimids such as Pelecanimimus are perceived to have been more predatory in their dietary needs. This is only speculation however, it remains to be seen to just what other surprises Deinocheirus may have in for us.

As one of the larger dinosaurs in its environment Deinocheirus probably only had to worry about other large theropod dinosaurs when fully grown, as late Cretaceous Asia seems to have been dominated by large tyrannosaurs such as Tarbosaurus and Zhuchengtyrannus. Tarbosaurus in particular may have been a particular threat given that a least one of the ribs discovered at the fossil site of the original arms shows tooth marks that were likely caused by a tyrannosaur, with Tarbosaurus also being known from that approximate location. If this was active predation or more imply a case of scavenging however is simply impossible to say. Aside from tyrannosaurs, Deinocheirus likely came into contact with other types of dinosaurs such as hadrosaurs, ceratopsians, dromaeosaurs, oviraptorids, therizinosaurs, pachycephalosaurs as well as the occasional titanosaur, all while early birds and pterosaurs flew on overhead.

Further Reading

- Third (1965) Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expedition to the Gobi Desert and western Mongolia. - Bulletin de l’Acad�mie Polonaise des Sciences, C1. II 14 (4): 249–252. - Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska - 1966. - Giant claws of enigmatic Mesozoic reptiles. - Paleontological Journal, 1970(1): 117-125. - A. K. Rozdestvensky - 1970. - Ornithomimids from the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia. - Journal of the Paleontological Society of Korea, 22(1): 195-207. - Y. Kobayashi & R. Barsbold - 2010. - Hip heights of the gigantic theropod dinosaurs Deinocheirus mirificus and Therizinosaurus cheloniformis, and implications for museum mounting and paleoecology. Bulletin of the Gunma Museum of Natural History, 14: 1-10. - P. Senter & H. J. Robins - 2010. - Tyrannosaur feeding traces on Deinocheirus (Theropoda:?Ornithomimosauria) remains from the Nemegt Formation (Late Cretaceous), Mongolia. - Cretaceous Research - Phil R. bell, Philip J. Currie & Young-Nam Lee – 2012. – New specimens of Deinocheirus mirificus from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia. – Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Abstracts of Papers: 161. – Y. N. Lee, R. Barsbold, P. J. Currie, Y. Kobayashi & H. J. Lee – 2013. – Resolving the long-standing enigmas of a giant ornithomimosaur Deinocheirus mirificus. – Nature. 515 (7526): 257–260. – Y. N. Lee, R. Barsbold, P. J. Currie, Y. Kobayashi, H. J. Lee – 2014. – First insights into the bone microstructure of Deinocheirus mirificus. – 13th Annual Meeting of the European Association of Vertebrate Palaeontologists: 25. – M. Kundr�t & Y. N. Lee – 2015. – Histological analysis of the gastralia of Deinocheirus mirificus from the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia. – 6th Annual Meeting Canadian Society of Vertebrate Palaeontology Ottawa, Ontario. Ottawa. p. 46. – B. Roy, M. J Ryan, P. J. Currie, E. B. Koppelhus & K. Tsogtbaatar – 2018.