In Depth

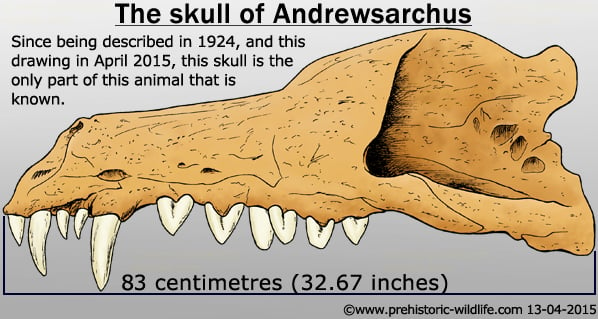

In popular culture, especially at the turn of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, Andrewsarchus has been presented as a huge predator, similar in form to other quadrupedal meat eating mammals, but powerfully built like a big cat or even a bear. However despite this reconstruction becoming very familiar in the public consciousness, palaeontologists are far more cautious as so far only the skull of this animal is known.

The popular reconstruction is based upon the concept that for a long time Andrewsarchus was envisioned as a larger relative of Mesonyx, a meat eating predator that is often described as wolf-like, although it actually appeared long before the emergence of true wolves. Later interpretations of Andrewsarchus however (one of best known being a 2009 study by Michelle Spaulding, Maureen A. O’Leary and John Gatesy) have since concluded that Andrewsarchus probably isn’t that closely related to Mesonyx. In fact today Andrewsarchus has been widely considered to be closer to primitive hippos or even enteledonts due to the long jaws with wide cheek bones.

The exact diet of Andrewsarchus has also been questioned as the previous older apex predator theories don’t carry as much weight as they used to. Although the jaws would have had tremendously powerful muscles (as indicated by the size of the cheek bones), most of the teeth in the mouth are not particularly well adapted for any one purpose. The forward canines are the largest and are most useful for getting a grip on things, or perhaps in the case of a carnivore to deliver a killing bite such as puncturing the cranium of a prey animal. Because the type specimen skull was found in what would have been a coastal environment during the Eocene, Andrewsarchus has been presented as a beach comber. Here Andrewsarchus may have had a durophagus diet that means it ate shellfish that it dug out with its forward teeth, although it may have included animals like turtles as well as washed up carrion. However while this skull proves that Andrewsarchus was active in coastal areas, it would be a mistake to assume that it was limited to them without the evidence of further remains. Aside from the skull being similar in form this has also led to some claiming that the behaviour of Andrewsarchus was similar to what has been proposed for enteledonts. This would see Andrewsarchus living the life of an opportunistic omnivore, as while Andrewsarchus is on paper capable of killing its own prey, it may have scavenged carcasses as well as driven off other predators from their kills. The forward teeth could also have been capable of digging up plant tubers that Andrewsarchus could have then eaten.

Since Andrewsarchus had a large skull it would need strong neck muscles to provide ample support. Although we still do not know for certain, it’s possible that the anterior dorsal vertebrae had enlarged neural spines (bony projections that rise upwards from the individual vertebra) that provided increased areas for muscle attachment. This is similar to how some other creatures with large skulls such as enteledonts supported their heads. If true then Andrewsarchus would in life have powerful powerfully built fore quarters which may have given rise to a small hump above its shoulders from the increased muscle mass from this area.

When Andrewsarchus was first compared to Mesonyx its missing body was estimated by scaling up the skull of Mesonyx to that of Andrewsarchus. This led to early size estimates of up to six meters long, something that saw Andrewsarchus being treated as possibly the largest meat eating mammal to ever walk the earth. However there are a number of problems with this estimate, the most obvious being the general consensus that Andrewsarchus was not like Mesonyx at all which automatically makes this size comparison flawed. Second is that it is impossible to say how heavily built Andrewsarchus was without seeing how things like muscles could attach to the skeleton.

For example the dire wolf (Canis dirus) is skeletally not much larger that the grey wolf (Canis lupus), but the bones are thicker and the muscle attachment points are much more strongly developed which indicates that it had a larger muscle mass making it a bigger animal. Also other large meat eating mammals such as the short faced bear Arctodus are very large, but have comparatively lightweight builds so that their immense size does not weigh them down. This is where the confusion about Andrewsarchus lies, as a terrestrial predator with a physically large skeleton needs some way to reduce its weight otherwise it’s simply too slow to catch anything. This might not be such a problem if Andrewsarchus could hunt large and equally slow prey, but this first needs to be available in sufficient quantities to keep the large body going, as well as a population to continue the species. Another argument that counts against Andrewsarchus being the largest ever carnivore is comparison to similarly large skulled animals like enteledonts. These animals also have large skulls and shoulder areas to support the head, but the main body itself is very gracile so as not to put too much strain upon the intake of food. Of course without more complete remains we will never know how large Andrewsarchus was, but while it is still treated by some as being one of if not the largest mammalian predator, most researchers prefer to consider large bears as the biggest terrestrial mammalian predators.

Like with many mammals the demise of Andrewsarchus may have been brought about by a combination of climate change and new animals appearing on the landscape. The rising Himalaya Mountains resulted in much of Asia becoming a drier expanse of plains which in turn created a shift towards different types of potential prey. Enteledonts also started to become widespread although they were mostly smaller varieties when compared to their giant forms of the early Miocene. New predators such as creodonts like Hyaenodon and the bear-like Sarkastodon were also beginning to fill the top predator niches.Andrewsarchus was named in honour of Roy Chapman Andrews.

Further Reading

– Andrewsarchus, giant mesonychid of Mongolia. – American Museum Novitates 146:1-5. – H. F. Osborn – 1924. – Relationships of Cetacea (Artiodactyla) Among Mammals: Increased Taxon Sampling Alters Interpretations of Key Fossils and Character Evolution. – PLoS ONE. 4 (9): e7062. – M. Spaulding, M. A. O’Leary & J. Gatesy – 2009.