In Depth

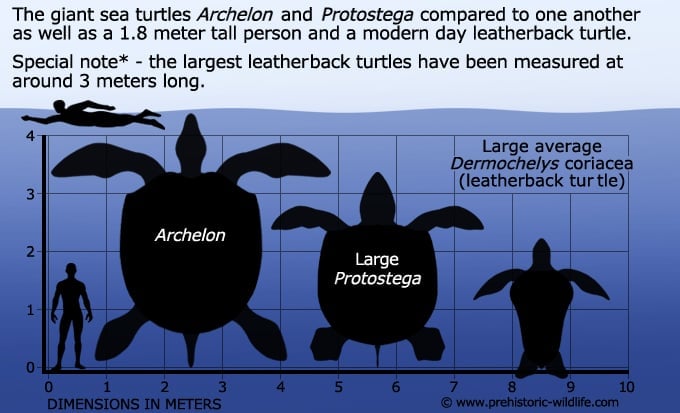

Although a turtle, Archelon has become a staple species that appears in almost every book about dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals. This almost mandatory inclusion comes from the fact that Archelon is the largest turtle ever known to exist and it lived at the end of the Cretaceous. For the most part dinosaurs were probably not a threat, as assuming Archelon laid eggs like turtles do today, it would only ever venture onto land to lay eggs. Conversely however these eggs would eventually hatch and the young may have had to run a gauntlet of predators on their way to the ocean. Back in the Cretaceous this could mean everything from small beach combing dinosaurs, primitive seabirds similar to Ichthyornis to even pterosaurs. Archelon is usually envisioned as being very similar to the leatherback turtle, and likely had a similar preference for eating jellyfish and cephalopods. The horned beak of the mouth which had a clear overbite would have been very effective at snipping soft bodied animals like these into bite sized portions that could be swallowed. Another similarity between these two turtles is that neither one has a solid shell. Instead a series of bony struts, that in Archelon are actually the ribs, create a framework of bone that an outer and relatively thin carapace sits on top of.

Perhaps the easiest explanation for Archelon’s shell design is that of neutral buoyancy. This is where a marine animal’s body adapts so that it neither floats to the surface, nor sinks to the bottom. In order to achieve this effect the body changes along such lines as denser thick bones that counter the lifting effect of the air in the lungs so that the animal does not bob around on the surface. Good examples for marine adaptation in reptiles can be seen in the placodonts from the Triassic which were actually negatively buoyant so that they could sink to the bottom where their preferred food was.

Archelon however was not a bottom feeder, it had to stay active in the mid to upper surface areas where its prey was most abundant, and as such it needed to be neutrally buoyant so that it could adapt to different depths wherever its prey was. As a large turtle Archelon obviously had a large shell, but if this shell was solid bone with a horn covering like in smaller turtles it would be extremely heavy. It’s feasible that a heavy solid shell would have tipped the scale into negative buoyancy so that Archelon would have had to spend a greater amount of energy just to stay up in the areas its food supply was, as well as rising up to breathe. This would not suit any animal, especially large ones like Archelon.

A shell composed of a framework with a relatively thin covering however would actually be very lightweight as well as reducing the body density so that Archelon did not readily sink as well as a more solid creature. This in turn would allow Archelon to cruise the oceans at a more leisurely pace and conserve energy so that it would not need as high a calorie intake as it would have done if the shell were solid.

The presence of large mosasaurs such as Tylosaurus as well as possibly even sharks like Cretoxyrhina suggest that Archelon probably was not invulnerable to predators, particular from attacks to the flippers. Despite this the sheer physical size of the shell may have still been enough to prevent some predators from being able to close their jaws around the body. At the very least this would have made a fully grown Archelon a difficult prey item compared to other softer bodied marine reptiles. Aside from this large size four star-shaped plates are found on the underside of the shell which seems to reinforce it. These may appear on the underside as a form of additional defence from predators that hit it from below. It’s perhaps not implausible that such attacks may have been initiated by mistake by predators that confused Archelon for a different kind of animal, possibly explaining the presence of these plates only on the underside.

Further Reading

– Archelon ischyros: a new gigantic cryptodire testudinate from the Fort Pierre Cretaceous of South Dakota. American Journal of Science – 4th Series 2(12):399-412, pl. v. – G. R. Wieland – 1896. – Notes on the Cretaceous turtles, Toxochelys and Archelon, with a classification of the marine Testudinata. – American Journal of Science, Series 4, 14:95-108, 2 text-figs. – G. R. Wieland – 1902. – Revision of the Protostegidae. – American Journal of Science, Series 4. 27(158):101-130, pls. ii-iv, 12 text-figs. – G. R. Wieland – 1909. – Vertebrate Biostratigraphy of the Smoky Hill Chalk (Niobrara Formation) and the Sharon Springs Member (Pierre Shale). – High-Resolution Approaches in Stratigraphic Paleontology, 21: 421-437 – K. Carpenter – 2003. – Skeleton of the Rare Giant Sea Turtle, Archelon, Recovered from the Cretaceous DeGrey Member of the Pierre Shale near Cooperstown, Griggs County, North Dakota. – North Dakota Geological Society Newsletter. 32 (1): 1–4. – J. W. Hoganson & B. Woodward – 2004.