In Depth

Ichthyornis - A brief history of the discovery and classification.

Ever since its first description in 1872, Ichthyornis has been one of the most important prehistoric birds known to us, but one that has been frequently mired in controversy. The very first specimen of Ichthyornis was first recovered in 1870 by Benjamin Franklin Mudge. Those who know their paleontological history will already know that at this time in North America the Bone Wars were in full swing. The Bone Wars were basically just the rivalry between two palaeontologists of the time named Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh, and while they resulted in a great many discoveries, the period is usually held as an example of how not to conduct palaeontology.

In 1870 Mudge was supplying his fossil discoveries to Cope but then things changed. Mudge had been a friend of Marsh in his younger years and Marsh decided to take advantage of this. This was always Marsh’s advantage over Cope in that he knew people in the right places to secure positions and work, and when he wrote to Mudge he asked him to send anything that he thought was significant to him instead of Cope. To sweeten the deal Marsh offered to do this for free and promised to give Mudge sole credit for the discovery. When Mudge received Marsh’s letter the first Ichthyornis specimen was already prepared for shipping to Cope; it ended up going to Marsh instead.

In their eagerness to outdo one another both Cope and Marsh missed several key things, and here Marsh failed to realise the importance of his bird specimen. Upon first study, Marsh thought that he had the remains of two creatures. The skeleton he thought belonged to a bird, no doubt about that, but there were long jaws had sharp teeth included with the pot cranial skeleton. At this time Marsh thought that these belonged to some reptile, possibly something like a small mosasaur. Marsh noted the unusual vertebrae of the bird skeleton and noted that they were concave (curved inwards) at both ends like those of fish. This yielded the rather simple name of Ichthyornis which means ‘fish bird’. The jaws were attributed to their own genus, Colonosaurus mudgei. By early 1873 Marsh had realised that he had made a big mistake. Further preparation of the rock that held the bones resulted in further exposure of the remains that yielded a very startling discovery; the toothed jaws were not those of a reptile, they belonged to the bird. Marsh immediately created the Odontornithes (toothed birds) and Ichthyornithes groups to classify his new discovery which was already sending shockwaves through the paleontological world. Ichthyornis became the first bird known to have had teeth within its jaws. For clarity, while Archaeopteryx was named in 1861 and was the first bird to be known from the Mesozoic age, the genus was not known to have had teeth as well until a specimen with a skull was described in 1884.

Ichthyornis was controversial. Charles Darwin’s Upon the Origin of Species had been first printed in 1859 and had upset a lot of people, particularly those with strong religious views who saw it as a challenge to the teachings of the Christian bible. Marsh’s specimen of Ichthyornis was a clear indicator that birds had a reptilian origin (today we now know this to be the theropod dinosaurs), and some people actually asked Marsh to hide the specimen away because it was such strong proof of evolution in action.

Others were less kind and instead accused Marsh of making a deliberate attempt at a hoax, and these claims have been as recent as 1967. As always however, time has allowed the truth to be determined without doubt. Ichthyornis is now known by many specimens; in fact it is one of the best represented fossil birds currently known. Other toothed birds of varying degrees of primitiveness are now also known, including Hesperornis, a genus of toothed bird that was different but lived in the same time and locations as Ichthyornis. Darwin himself considered both Hesperornis and Ichthyornis to represent important links in our understanding of evolution.

Due to the large number of fossil remains, Ichthyornis now has many synonyms accredited to it. Obviously Colonosaurus mudgei, the name given to just the jaws in 1872 is a synonym but so is Angelinornis and two species of Graculavus, G. anceps and G. agilis. Ichthyornis was one broken down into many species but today only the type species is universally considered as valid. Older species are either synonyms to the type species or have been moved to other genera. Remains from Uzbekistan once thought to belong to the genus were later named as Austinornis.Ichthyornis - The bird.

In the simplest terms, Ichthyornis was a sea bird that was probably very similar to modern gulls in terms of ecological niche. As already mentioned, remains from Uzbekistan are no longer thought to belong to the genus, so the distribution of Ichthyornis is now the central portion of North America. This indicates that Ichthyornis lived along the coastline of the old Western Interior Seaway. This was a shallow sea that submerged most of central North America during the late Cretaceous.

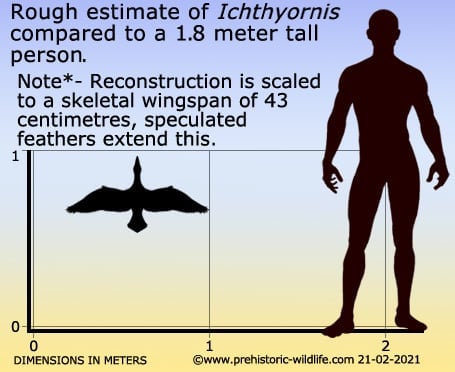

By the time of Ichthyornis birds had become competent flyers. The wing structure of Ichthyornis is more or less the same as in modern bird forms meaning that the wings were capable of performing efficient flight strokes. The skeletal wingspan of Ichthyornis is about forty-three centimetres long, but in life this would have been extended by the presence of flight feathers. The exact size of the wing is still uncertain because the flight feathers are still unknown.

The sternum of Ichthyornis also display a strongly developed keel-like growth that projects forward. This bone would have been the main attachment point for strong pectoral muscles that would have enabled repetitive flapping of the wings to keep the bird in the air. The addition of fused metacarpals in the wings and presence of a pygostyle also indicate that Ichthyornis could make finer flight controls while in the air than far more primitive forms earlier in the Cretaceous and Jurassic. These features would have allowed Ichthyornis to fly out over the open sea for extended periods as well as possibly exploit air currents over the water’s surface.

Rather than being a single sheet of keratin, the beak of Ichthyornis was composed of several segments that formed a whole, the beak of the albatross would be a modern analogy to this. The teeth of Ichthyornis were laterally compressed (flattened to the sides) and the tips were recurved so that they pointed towards the rear of the mouth. A key note about the teeth is that they were only present in the middle portion of the mouth, the front portion is completely lacking. The teeth themselves likely facilitated prey capture of marine organisms such as late Cretaceous fish that swam too close to the surface.

Further Reading

- Notice of a new reptile from the Cretaceous - Othniel Charles Marsh - 1872. - Notice of a new and remarkable fossil bird - Othniel Charles Marsh - 1872b. - On a new sub-class of fossil birds (Odontornithes) - Othniel Charles Marsh - 1873. - The jaws of the Cretaceous toothed birds, Ichthyornis and Hesperornis - J. T. Gregory - 1952. - Marsh was right: Ichthyornis had a beak - J. P. Lamb Jr - 1997. - Bone microstructure of the diving Hesperornis and the volant Ichthyornis from the Niobrara Chalk of western Kansas - A. Chinsamy, L. D. Martin & P. Dobson -1998. - Vertebrate Biostratigraphy of the Smoky Hill Chalk (Niobrara Formation) and the Sharon Springs Member (Pierre Shale) - K. Carpenter - 2003. - Morphology, phylogenetic taxonomy, and systematics of Ichthyornis and Apatornis (Avialae: Ornithurae) - J. A. Clarke - 2004. - Ichthyornis sp. (Aves: Ichthyornithiformes) from the lower Turonian (Upper Cretaceous) of western Kansas - K. Shimada & M. V. Fernandes - 2006.