In Depth

Alioramus has stirred a lot of interest and controversy since its discovery, and even though Alioramus has earned worldwide popularity it was for a long time only known from a partial skull and three metatarsals (foot bones). Another problem was the fact that when reconstructed, the skull was narrow and low like in some juvenile forms of other better known tyrannosauroids. This led to Alioramus being considered for a long time to be a juvenile of the larger Tarbosaurus by many palaeontologists until the discovery of the second species A. altai in 2009. This specimen is thought to represent a sub-adult because the skull bones had begun fusing together, indicating that the individual was approaching maximum size but still not even close to Tarbosaurus. Further support for keeping Alioramus its own separate genus comes from the fact that Alioramus had many more teeth in its mouth than Tarbosaurus individuals that were both juvenile and fully grown. Also Alioramus has a series of five crests on the top of its snout which so far remain unknown in Tarbosaurus.

There has in the past been a proposed synonymy between Alioramus and the genus Qianzhousaurus. However later study of Qianzhousaurus fossils have cast doubt upon this idea, and the two genera are generally regarded as very similar but different, The two genera are now more often placed in their own group within the Tyrannosauroidea, known as the Alioramini..Hunting and potential prey specialisation

The legs of Alioramus had proportionately longer lower limb segments, an arrangement that is reminiscent of the fast running ornithomimid dinosaurs like Gallimimus. Bearing in mind that the Alioramus specimen in question was a sub adult, the longer legs do fit in with the tyrannosauroid body morphs for younger individuals. Tyranosauroid genera where the juvenile as well as adult individuals are known, such as Albertosaurus, consistently shows that tyrannosauroids had proportionately longer legs when young that proportionately shortened as the individual grew to adult size. This is a simple adaptation that allowed small tyrannosauroids to hunt small and fast prey until they grew larger when they would need to hunt larger but slower prey to maintain an adequate food intake. However, the only currently known limb remains for Alioramus come from the second species A. altai, and this individual is thought to be a subadult.

Without further remains attributable to a younger juvenile or even better a full grown adult, it is impossible to say how short the legs of Alioramus became. But the fact that the legs still retain fast running proportions at a stage when its overall growth would be slowing down suggests that Alioramus was relatively quick and nimble when compared to other medium to large members of the Tyrannosauroidea. Combined with its more gracile build and it may well be that Alioramus was a niche specialist that hunted dinosaurs that were too swift for the larger Tarbosaurus to catch.

The large number of moderately sized and relatively evenly spaced and arranged teeth also suggests a specialisation for fast but unarmoured prey as these would provide a greater area for seizing prey. The narrow skull also meant proportionately weaker biting muscles than other tyrannosauroids suggesting that Alioramus went to work on softer and unarmoured flesh. Large tyrannosauroids like Daspletosaurus and Tyrannosaurus by comparison have fewer but larger teeth, and deep snouts to house powerful biting muscles to drive those teeth through bone, feeding behaviour which is also confirmed by fossil evidence.

The fact that Alioramus was present in the same location as Tarbosaurus also follows a trend of a robust and gracile morph split between two tyrannosauroid genera per area that seems to have repeated itself. Such a niche split can also be seen in North America during the Campanian with Daspletosaurus (robust) and Gorgosaurus (gracile) crossing territories, and during the Maastrichtian with Tyrannosaurus (robust) and Albertosaurus (gracile) also having similar approximate areas.Body shape and form

The name Alioramus translates as ‘different branch’ and is in reference to Alioramus’s different head and body shape to other tyrannosauroids. The head shape of Alioramus is more like the earlier basal members of the Tyrannosauroidea that were generally smaller theropods that focused on smaller and less powerful prey. The fact that Alioramus still has this overall shape suggests that while Alioramus was related to other tyrannosauroids it was actually passing along a different evolutionary path that allowed the retention of this more basal feature.

The most distinctive features of Alioramus are five one centimetre high ridges that run across the top of its snout. Head ornamentation is virtually unknown in the later and larger tyrannosauroids, although some earlier members such as Guanlong did actually have quite elaborate head crests. It could be that the head ornamentation of Alioramus is a throwback to these earlier forms and its retention is actually a sexually selected characteristic with the most developed ridges being the most attractive to others of their kind. It’s also possible that the ridges may have allowed Alioramus to differentiate between members of its own genera and juvenile Tarbosaurus that may have looked roughly similar.

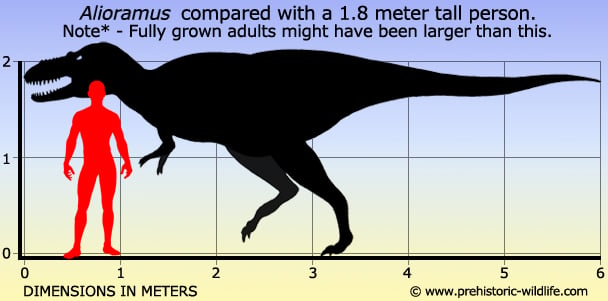

Another area of contention is the estimated size of Alioramus. When the first specimen was discovered the individuals size had to be estimated by comparison of the incomplete skull of the holotype to other more complete examples. This yielded an estimated length of between five and six meters, however the skull material was slightly deformed during the fossilisation process, a result of the extreme pressure the bones were subjected to with increasing layers of sediment being deposited on top of the bones. This led to the original length being considered an overestimate of the actual living animal, however the discovery of A. altai has since confirmed that six meters was probably easily possible for a full grown adult Alioramus, if not a conservative estimate. Unfortunately without fossil material from a confirmed fully grown adult Alioramus, it remains impossible to say for certain.

Further Reading

– A new carnosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Nogon-Tsav, Mongolia – The Joint Soviet-Mongolian Paleontological Expedition Transactions (in Russian) 3: 93–104. – Sergei M. Kurzanov – 1976. – Theropods from the Cretaceous of Mongolia – The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 434–455. ISBN 978-0-521-54582-2. – Philip J. Currie – 2000. – A long-snouted, multihorned tyrannosaurid from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia – Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. online preprint (41): 17261–6. – Stephen L. Bursatte, Thomas D. Carr, Gregory M. Erickson, Gabe S. Bever & Mark A. Norell – 2009. – Variation, Variability, and the Origin of the Avian Endocranium: Insights from the Anatomy of Alioramus altai (Theropoda: Tyrannosauroidea) – PLOS Collections. – Gabe S. Bever, Stephen L. Brusatte, Amy M. Balanoff & Mark A. Norell – 2011. – The osteology of Alioramus, a gracile and long-snouted tyrannosaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the late Cretaceous of Mongolia. – American Museum Novitates (366): 1−197. – Stephen L. Brusatte, Thomas D. Carr & Mark A. Norell – 2012.