In Depth

Yutyrannus is a good example of a tyrannosaur that had feathers, although it is not the first or only known tyrannosaur to have had feathers like some news reports claimed at the time of its discovery.

The first tyrannosaur to be feathered was actually Dilong which was named in 2004 and is actually also known from the Yixian Formation of China.

The feather covering of Yutyrannus is on different parts of the three specimens recovered, but when pieced together it seems that Yutyrannus had a covering of feathers all over its body.

The feathers themselves were most likely simple in structure and provided insulation, but palaeontologists have not yet ruled out the possibility that some of these feathers might have had a display purpose.

Although the discovery of Yutyrannus has once again raised the question of ‘were all tyrannosaurs feathered?’ Skin impressions of Tyrannosaurus reveal a scaly skin, suggesting that this genus at least did not.

It needs to be remembered that since feathers initially evolved for insulation, the development and presence of feathers depends more upon environmental conditions rather than just the size of the dinosaur.

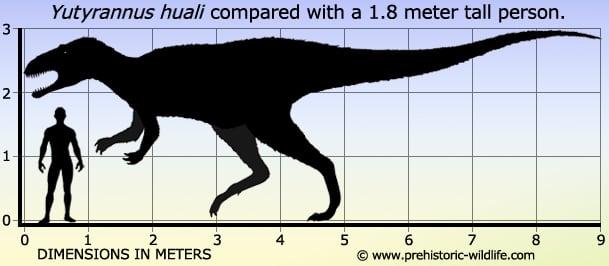

Currently Yutyrannus is regarded as being the biggest feathered dinosaur, being forty times heavier than the previous record holder, a therizinosaur named Beipiaosaurus.

Yutyrannus is considered to be a basal tyrannosauroid, one feature revealing this being the foot which is non-arctometatarsalian.

This means that Yutyrannus lacks the specially adapted middle toe that helped support the weight of the body and absorb stresses when running.

Yutyrannus also had a three fingered hand rather than the two fingered forms of late Cretaceous tyrannosaurs like Tyrannosaurus and Tarbosaurus.

When compared to other basal tyrannosaurs, Yutyrannus is placed at being more advanced than Guanlong which is also known from China, but not as advanced as Eotyrannus from England.

Yutyrannus also has a high midline crest on top of its snout that may have been for display and identification like the crest of Guanlong or the ridges of Alioramus.

Yutyrannus has not just raised more attention for large feathered dinosaurs, it has also raised other questions regarding tyrannosaur behaviour, specifically, ‘did tyrannosaurs hunt in packs?’ and/or ‘did they live in family groups?’

The fact that two juveniles were found with an adult does lend some support to the latter question, and it’s not the first time that juveniles have been found near adult tyrannosaurs.

The pack hunting theory however is a little harder to establish.

Some palaeontologists recognise that tyrannosaurs might have formed mixed groups where the smaller more agile juveniles would drive prey towards the jaws of an adult tyrannosaur that was better able to make a kill.

Others however have hypothesised that they may have been like komodo dragons and killed each other in competition over a carcass.

The latter theory would require the body of another dinosaur, assuming the carcass was not one of the tyrannosaurs to begin with.

However there is a massive concentration of Albertosaurus remains in Canada from many individuals and so far no other types of dinosaur are known from this bone bed.

An unrelated theropod from South America called Mapusaurus that is also known from a bone bed of many individuals but no other dinosaurs.

Slightly less weighty evidence is the discovery of three Daspletosaurus with the remains of five hadrosaurs.

Assuming that the collection of three individuals is not some freak random occurrence such as a flood washing together only three Yutyrannus and no other dinosaurs together, this may yet indicate further evidence for the support of pack hunting in dinosaurs, particularly the large theropods.

If you would like to know more about the arguments for and against pack hunting in dinosaurs in greater detail, then read the article ‘Pack Hunting Dinosaurs’.

Further Reading

– A gigantic feathered dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of China. – Nature 484 (7392): 92–95. – Xing Xu, Kebai Wang, Ke Zhang, Qingyu Ma, Lida Xing, Corwin Sullivan, Dongyu Hu, Shuqing Cheng & Shuo Wang – 2012.