In Depth

Massospondylus was one amongst the first dinosaurs to be named with a taxonomic history going back as far as the mid nineteenth century. Yet when Richard Owen described the first fossils, he thought that he was dealing with an ancient ancestor to more familiar lizards such as iguanas chameleons. In actuality Massospondylus represents a genus of sauropodomorph dinosaur, a group of dinosaurs that links the later sauropods to their bipedal saurischian ancestors.

Partly due to its long age and also a lack of understanding about dinosaurs in the early years of palaeontology, Massospondylus ended up with more fossil material than was necessary, resulting in a large number of species being established for the genus. Studies by later palaeontologists however have now found that many of these species actually represent other genera, leaving only the type species M. carinatus, as well as one other species M. kaalae being valid as of 2014. Some other genera of sauropodomorph dinosaurs have also been considered to be synonyms to Massospondylus, though opinions as to which are correct varies between different palaeontologists.

As stated above, Massospondylus was a sauropodomoprh dinosaur, though older texts may reference the genus as a prosauropod, the old name for describing the sauropodomoprhs that has now fallen out of favour by palaeontologists. The sauropodomorph dinosaur like Massospondylus are somewhere between early theropod dinosaurs and later sauropods, and exactly which side they are closer to depends more upon the genus. Massospondylus is currently thought to have been more bipedal (mostly walking on two legs), though many other sauropodomorphs were more quadrupedal. The neck of Massospondylus was quite long, even when compared to other sauropodomorphs.

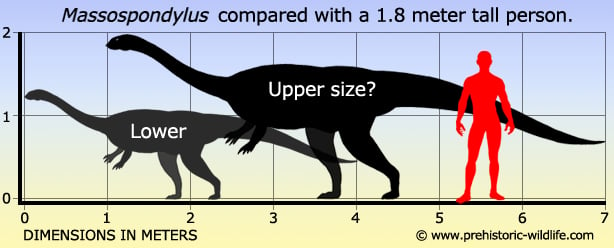

Size estimates for Massospondylus range between four and six meters long, and depending upon the validity of the fossils being measured, may indicate that the size of Massospondylus was highly variable. Size variation is not that unusual in sauropodomorph dinosaurs though, with the genus Thecodontosaurus being estimated between one and two and a half meters long, and Anchisaurus being two meters long, but possibly as much as four meters if the genus Ammosaurus is a synonym to it. If Massospondylus grew mostly to around 4 meters long then the genus would be comparable to others like Seitaad and Sarahsaurus. However other genera such as Aardonyx and Efraasia are estimated to have been around six meters long, meaning that larger sauropodomorph dinosaurs were not uncommon.

Massospondylus has been considered to have grown in relation to food availability, a theory that has also been proposed for its more famous relative Plateosaurus. What this means is that when food was plentiful, more energy was available for growth, and so individual Massospondylus grew larger during these times. When food was scarce however, growth may have been stunted through lack of nutrients and energy that supported bone growth. What is known to us though is that Massospondylus grew for a long time with one studied specimen being revealed in a 2001 study by Erickson et al to have come from an individual Massospondylus that was fifteen years old, and yet was still growing at the time of death.

Massospondylus is noted for having two kinds of teeth, small pointed teeth similar to those of the theropods in the anterior (front) part of the mouth, and spatulate teeth in the posterior (rear) of the mouth. This mix of teeth are the main cause of contention in determining the diet of Massospondylus, and indeed many other sauropodomorph dinosaurs, as the two forms would have enabled them eat anything from meat to plants. The spatulate teeth of Massospondylus at least show a shift towards a more herbivorous diet, and studies of the skull and jaw mechanics of Massospondylus and other sauropodomorphs indicate that these dinosaurs were better adapted to a herbivorous diet. There continues to be speculation however that sauropodomorphs like Massospondylus may have still fed upon carrion and possibly even small vertebrates like lizards, especially if alternative plant sources were scarce. The number of teeth varies between Massospondylus, with those that have larger skulls having more teeth.

There has frequently been questions as to whether sauropodomoprhs and even sauropods used gastroliths to aid digestion, and for Massospondylus rounded stones that may have been used as gastroliths have been found with at least one specimen. A 2007 study by Wings and Sander however came to the conclusion that gastroliths were not used by sauropod dinosaurs. Gastroliths however do seem to have been used by some dinosaur genera however, with the theropod Lourinhanosaurus being one.

The skulls of Massospondylus have the revealed the placement of large blood vessels that quite likely supplied oxygenated blood to cheeks. These cheeks would have covered the sides of the mouth much like your own, and prevented food from falling out while it was being processed by the teeth. This also supports a more herbivorous diet as plant material usually needs to be chewed before eaten, especially if there were now gastroliths present.

Massospondylus is believed to have had at least a partially avian-like respiratory system, however, like other sauropodomorphs, Massospondylus does not show pneumatic opening in the bones, openings which are more clearly visible within theropods and sauropods. Instead air sacs in Massospondylus are believed to have been more within the body. Despite the lack of bone evidence for this system, Massospondylus and other sauropodomorphs almost certainly had an avian-like system. More intensive studies of such systems dating back to the late twentieth and early twenty-first century have now revealed that the avian style system of respiration goes as far back as dinosauromorphs and possibly even earlier archosaurs.

Clutches of Massospondylus eggs are known and study of these have revealed the embryos that were inside of them. From this we now know that newly hatched Massospondylus would have been quadrupedal and not bipedal until older. Newly hatched Massospondylus also lacked teeth. The arrangement of the eggs also shows that the eggs were thin shelled and pushed together by the parent Massospondylus. Beyond this there is no evidence for extensive nest building.

The mid-sized theropod Dracovenator lived at the same approximate time and location as Massospondylus, and may have been a predator. If this is true, then this would mean that the early Jurassic of Southern Africa resembled the early Jurassic of North America where predators like Dilophosaurus, a relative to Dracovenator, probably hunted sauropodomorph dinosaurs too.

Further Reading

- Descriptive catalogue of the Fossil organic remains of Reptilia and Pisces contained in the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. - London 1-184 - Richard Owen - 1854. - Note on certain vertebrate remains from the Nagpur district - Records of the Geological Survey of India 23 (1): 21–24. - Richard Lydekker - 1890. - On the type of the genus Massospondylus and on some Vertebrae and limb-bone of M. (?) browni - Annals and Magazine of Natural History 15: 102–125. - H. G. Seeley - 1895. - On the dinosaurs of the Stormberg, South Africa - Annals of the South African Museum 7 (4): 291–308. - Robert Broom - 1911. - The fauna and stratigraphy of the Stormberg Series - Annals of the South African Museum 12: 323–497. - Sydney H. Haughton - 1924. - The prosauropod dinosaur Massospondylus carinatus Owen from Zimbabwe: its biology, mode of life and phylogenetic significance - Occasional Papers of the National Museums and Monuments of Rhodesia, Series B, Natural Sciences 6 (10): 689–840. - M. R. Cooper - 1980. - The southern Liassic prosauropod Massospondylus discovered in North America - Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 5 (2): 128–132. - J. Attridge, A. W. Crompton & F. A. Jenkins Jr.- 1985. - Skulls of the prosauropod dinosaur Massospondylus carinatus Owen in the collections of the Bernard Price Institute for Palaeontological Research - Palaeontologia Africana 27: 45–58. - C. E. Gow, J. W. Kitching & M. K. Raath - 1990. – Morphology and growth of the Massospondylus braincase (Dinosauria, Prosauropoda) - Palaeontologia Africana 27: 59–75. - C. E. Gow - 1990. - Ontogenetic growth of the dinosaurs Massospondylus carinatus and Syntarsus rhodesiensis”. In: Abstracts of papers. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, fifty-second annual meeting. Royal Ontario Museum Toronto, Ontario - Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 12 (3): 23A. - A. Chinsamy - 1992. - The first South American record of Massospondylus (Dinosauria: Sauropodomorpha) - Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Abstracts of papers. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, 20–23 October, 19, Suppl. 3, 61A. - R. Martinez - 1999. - Massospondylus (Dinosauria: Sauropodomorpha) in northwestern Argentina - Abstracts VII International Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems, Buenos Aires, 40. - R. N. Martinez - 1999. - Dinosaurian growth patterns and rapid avian growth rates - Nature 412 (6845): 429–433. - Gregory M. Erickson, Kristina Curry Rogers & Scott A. Yerby - 2001. - The cranial anatomy of Massospondylus carinatus Owen, 1854 and its implications for prosauropod phylogeny - Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Abstracts of papers. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, 22, Supplement to number 3, 65A. - S. Hinic - 2002. - On the skull of Massospondylus carinatus Owen, 1854 (Dinosauria: Sauropodomorpha) from the Elliot and Clarens formations (Lower Jurassic) of South Africa - Annals of Carnegie Museum 73 (4): 239–257. - H. -D. Sues, R. R. Reisz, S. Hinic & M. Raath - 2004. - Furcula-like clavicles in the prosauropod dinosaur Massospondylus - Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25 (2): 466–468. - Adam M. Yates & Cecilio C. Vasconcelos - 2005. - Developmental plasticity in the life history of a prosauropod dinosaur - Science 310 (5755): 1800–1802. - Martin P. Sander & Nicole Klein - 2005. - Basic avian pulmonary design and flow-through ventilation in non-avian theropod dinosaurs - Nature 436 (7048): 253–256. - Patrick M. O’Connor & Leon P. A. M. Claessens - 2006. - Were the basal sauropodomorph dinosaurs Plateosaurus and Massospondylus habitual quadrupeds? - In Paul M. Barrett & D. J. Batten (eds.). Evolution and Palaeobiology of Early Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Special Papers in Palaeontology 77. London: The Palaeontological Association. pp. 139–155. - Matthew S. Bonnan & Phil Senter - 2007. - No gastric mill in sauropod dinosaurs: new evidence from analysis of gastrolith mass and function in ostriches - Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 274 (1610): 635–640. - O. Wings & P. Martin Sander - 2007. - What pneumaticity tells us about ‘prosauropods’, and vice versa. - Special Papers in Palaeontology 77: 207–222. - Mathew Wedel - 2007. - A new basal sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Upper Elliot Formation (Lower Jurassic) of South Africa - Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29 (4): 1032–1045. - P. M. Barret - 2009. - Embryonic Skeletal Anatomy of the Sauropodomorph Dinosaur Massospondylus from the Lower Jurassic of South Africa - Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30 (6): 1653, 1664 - Robert R. Reisz, David C. Evans, Hans-Dieter Sues & Diane Scott - 2010. - Massospondylus carinatus Owen 1854 (Dinosauria: Sauropodomorpha) from the Lower Jurassic of South Africa: Proposed conservation of usage by designation of a neotype - Palaeontologia Africana 45: 7–10. - Adam M. Yates & Paul M. Barret - 2010. Reassessment of the Evidence for Postcranial Skeletal Pneumaticity in Triassic Archosaurs, and the Early Evolution of the Avian Respiratory System - Plosone - Richard J. Butler, Paul M. Barret, David J. Gower - 2012.