In Depth

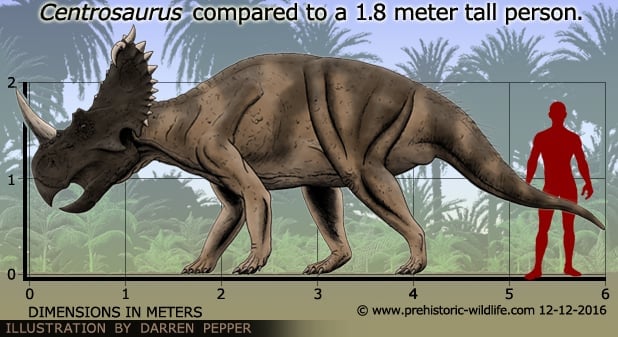

Centrosaurus acquired its named from the numerous bony projections that run along the edges of its frill. Aside from these a large nasal horn extends upwards from the top of the snout, and a pair of small horns project from the eyebrow. Two more hornlets hook down from the top of the frill, although how developed they are depends upon the species, being most pronounced in C. apertus. The nasal horn is also known to curve either forwards or backwards, and may be indicative of species.

Even though it was not large for a ceratopsian, Centrosaurus was not small either. Remains of numerous individuals including the remains of several hundred dinosaurs in a bone bed indicate that Centrosaurus was one of the most common dinosaurs of the time and location, and may have moved around in herds numbering hundreds of individuals. However, the herding theory is but one interpretation of the site ait may also indicate a doomed watering hole that vanished during a drought. Study of the bone bed has also revealed Styracosaurus remains on top of the Centrosaurus remains, leaving some to believe that Styracosaurus may have displaced Centrosaurus as the main herbivore of the area.

Centrosaurus has been used as the base of the ceratopsian group centrosaurinae. The ceratopsian dinosaurs of this group are noted for having short neck frills and single nasal horn, although some members do have brow horns, as well as further spikes that can and often do extend from the edges of the frill. Other ceratopsains of the centrosaurinae include Einiosaurus, Styracosaurus, Diabloceratops and Pachyrhinosaurus among others.

Centrosaurus was also at the centre of a naming controversy in 1915 with the discovery and naming of the stegosaurid Kentrosaurus. Although alternative names for Kentrosaurus were created, they were not needed as it was still spelled differently to Centrosaurus. On top of this they are also pronounced differently, Kentrosaurus with a kicking ‘K’, and Centrosaurus with a soft ‘C’ pronounced as ‘See’.

Further Reading

– On the squamoso-parietal crest of the horned dinosaurs Centrosaurus apertus and Monoclonius canadensis from the Cretaceous of Alberta – Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada, series 2 10(4):1-9 – 1904. – On the status of the ceratopsids Monoclonius and Centrosaurus – P. Dodson – 1990 – In K. Carpenter & P. J. Currie (eds.). Dinosaur Systematics: Perspectives and Approaches. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 231–243. – Taphonomy of three dinosaur bone beds in the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation, northwestern Montana: Evidence for drought-related mortality – PALAIOS (SEPM Society for Sedimentary Geology) 5 (5): 394–41 – R. R. Rogers – 1990. – Craniofacial ontogeny in centrosaurine dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Ceratopsidae): taphonomic and behavioral phylogenetic implications – Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 121 (3): 293–337 – S. D. Sampson, M. J. Ryan & D. H. Tanke – 1997. – Ceratopsian bonebeds: occurrence, origins, and significance – David A. Eberth & Michael A. Getty – 2005 – In Dinosaur Provincial Park: A Spectacular Ancient Ecosystem Revealed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 501–536 – Phillip J. Currie & Eva Koppelhus. – A new centrosaurine ceratopsid from the Oldman Formation of Alberta and its implications for centrosaurine taxonomy and systematics – Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 42 (7): 1369–1387 – M. J. Ryan & A. P. Russel – 2005. – Craniofacial ontogeny in Centrosaurus apertus. – PeerJ – J. A. Frederickson & A. R. Tumarkin-Deratzian – 2014. – First case of osteosarcoma in a dinosaur: a multimodal diagnosis”. The Lancet Oncology. 21 (8): 1021−1022. – Seper Ekhtiari, Kentaro Chiba, Snezana Popovic, Rhianne Crowther, Gregory Wohl, Andy Kin On Wong, Darren H Tanke, Danielle M Dufault, Olivia D Geen, Naveen Parasu, Mark A Crowther & David C Evans – 2020.