In Depth

Wiwaxia was originally described back in 1899 by W. D. Matthew. However this description was based upon just one of the dorsal spines that rise up from the back of Wiwaxia, something that was realised in 1911 when more complete specimens were discovered by Charles Doolittle Walcott. However in Doolittle’s description, Wiwaxia was classed as a polycheate worm, something that would remain until 1985 when Simon Conway Morris published a more detailed description.

Wiwaxia possessed a small squat body that when seen from above looked elliptical, like a slightly squashed circle. When Wiwaxia is viewed in cross section from either the front or the rear however it was distinctly rectangular, with a small protuberance around the bottom. This has resulted in the sides being identified into three portions of upper lateral, lower lateral (where the protuberance meets the upper lateral) and the ventro-lateral where the body meets the ground. From above there is no clear growth that indicates a head, but the direction the sclerites overlap in may indicate which end is the front.

The sclerites are ridged scales that covered the body of Wiwaxia forming basic armour. The root of the sclerite was about the equivalent of forty per cent the external size and anchored into a skin pocket. The way the sclerites overlapped each other meant that the root of an individual sclerite was easily covered by the sclerite that overlapped it. This meant that the sclerites formed a firm yet flexible defence, especially from predators that had suction type mouths intended to work on soft bodied animals.

Most of these sclerites were oval shaped with the exception of the ones on the ventro-lateral edge. Instead of being oval these formed a crescent shape, presumably because of their close contact with the seafloor. The number of sclerites on any given Wiwaxia individual seemed to vary, but the easiest way is to count the number of rows. Dorsal rows (the ones than ran across the back) number between eight and nine. The upper lateral areas (roughly top two thirds of the sides) have between eleven and twelve. The lower lateral area (the thickened base portion that faced slightly upwards) had eight. The ventro-lateral area (which faced slightly downwards and had the crescent shaped sclerites) had between twelve and seventeen rows.

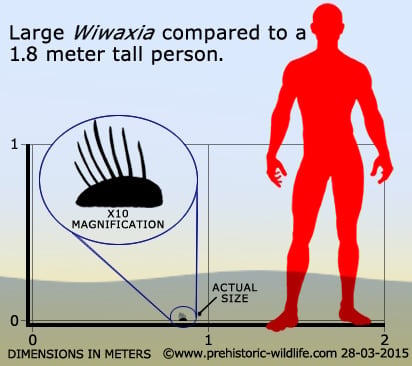

It should be remembered that the number of sclerites was not necessarily determined by the age of the individual, as study of different sized specimen’s revealed sclerites that grew proportionately with the increased size. In essence this means that Wiwaxia simply grew bigger rather than growing extra parts. As for the overall size of Wiwaxia, specimens that are between two and five centimetres long are considered to be adults, with smaller specimens juveniles. Because Wiwaxia had a soft body it is always preserved flat which has made it difficult to determine how tall Wiwaxia was in life. However gauging the height is not just dependent upon the orientation of the fossil, but can be estimated from how large the associated dorsal spines are and where they attach to the body. Height estimates for a Wiwaxia individual of thirty-four millimetres length is often quoted at being ten millimetres high.

The features of Wiwaxia that are most immediately visible are the dorsal spines that run along the back in two rows. While the smaller sclerites provided a closer internal defence these spines seem to have been the front line defence for Wiwaxia. Not only do these spines show signs of damage and irregular growth suggesting predation, Wiwaxia does not seem to have had eyes making it impossible for the spines to have been used for display.

The spines themselves were rooted in pits in the skin like the sclerites, however only about twenty-five per cent of their external length was the root. Usually the spines in the middle of the rows were tallest, but are sometimes smaller through damage and replacement. Like many other animals that lose body parts, the spines were replaced if lost, although also like other animals that have this ability, replacement is faster and more complete in younger individuals, especially juveniles that are still in their active growth stage. On top of this the actual number of spines can vary between individuals, including those that do not appear to have lost any. At up to five centimetres long, the dorsal spines are also the most common fossils of Wiwaxia, being considerably more numerous than complete specimens.

The only unarmoured part of Wiwaxia was the underside and this is also where the mouth was located. The mouth was located roughly one fifth of the total body length from the front of Wiwaxia and usually housed two rows of teeth, although large specimens are known to have three rows. The teeth in these rows were conical and faced backwards. The teeth were also packed tightly together in their rows together forming a single scraper that seemed to be folded in a ‘V’ shape when at rest, but extended out into a straight edge when used for feeding.

It is possible that Wiwaxia used this mouth to feed upon the microbial mats that covered the sea floors at the Beginning of the Cambrian. As the Cambrian period continued a process that is referred to as the Cambrian substrate revolution occurred. This was basically newly evolving animals burrowing beneath the microbial mats and slowly exposing the anoxic sediment underneath to a combination of water and oxygen. This resulted in the underlying sediment becoming habitable to more animals which in turn increased the process further which resulted in the eventual loss of the microbial mats. The loss of the microbial mats towards the end of the Cambrian may explain why Wiwaxia is so far only known from the early and middle stages of the Cambrian.

Further Reading

– The Middle Cambrian metazoan Wiwaxia corrugata (Matthew) from the Burgess Shale and Ogygopsis Shale, British Columbia, Canada. – Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 307 (1134): 507–582. – S. Comway Morris – 1985. – A reassessment of the enigmatic Burgess Shale fossil Wiwaxia corrugata (Matthew) and its relationship to the polychaete Canadia spinosa. Walcott. – Paleobiology 16 (3): 287–303. – N. J. Butterfield – 1990. – Wiwaxia from Early-Middle Cambrian Kaili Formation in Taijiang, Guizhou. – Acta Palaeontologica Sinica 33 (3). – Y. L. Zhao, Y. Qian & X. S. Li – 1994. – Original Molluscan Radula: Comparisons Among Aplacophora, Polyplacophora, Gastropoda, and the Cambrian Fossil Wiwaxia corrugata. – Journal of Morphology 257 (2). – A. H. Scheltema, K. Kerth & A. M. Kuzirian – 2003. – A reevaluation of Wiwaxia and the polychaetes of the Burgess Shale. – Lethaia 37: 317. D. Eibye-Jacobsen – 2004. – Mouthparts of the Burgess Shale fossils Odontogriphus and Wiwaxia: Implications for the ancestral molluscan radula. – Proceedings of the Royal Society B 279 (1745): 4287–4295. – M. R. Smith – 2012. – Ontogeny, morphology and taxonomy of the soft-bodied Cambrian ‘mollusc’ Wiwaxia. – Palaeontology vol 57, issue 1. – Martin R. Smith – 2013. – New Wiwaxia material from the Tsinghsutung Formation (Cambrian Series 2) of Eastern Guizhou, China. – Geological Magazine 151 (02): 339–348. – H. J. Sun, Y. L. Zhao, J. Peng & Y. N. Yang – 2014. – Articulated Wiwaxia from the Cambrian Stage 3 Xiaoshiba Lagerst�tte. – Scientific Reports 4:4643. – J. Yang, M. R. Smith, T. Lan, J.-B. Hou & X.-G. Zhang – 2014. – Ontogeny, morphology and taxonomy of the soft-bodied Cambrian ‘mollusc’ Wiwaxia. – Palaeontology 57 (1). – M. R. Smith – 2014. – First report of Wiwaxia from the Cambrian Chengjiang Lagerst�tte. – Geological Magazine 152 (2): 378–382. – F. C. Zhao, M. R. Smith, Z. -J. Yin, H. Zeng, S. -X Hu, G. -X Li & M. – Y. Zhu – 2015. – New reconstruction of the Wiwaxia scleritome, with data from Chengjiang juveniles. – Scientific Reports. 5. – Zhifei Zhang, Martin R. Smith & Degan Shu – 2015.