In Depth

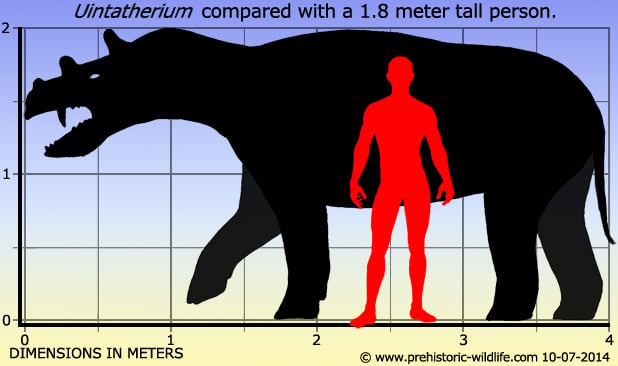

Imagine a rhinoceros with several smaller horns on top of its head and forward teeth similar to a sabre-toothed cat and you have a rough idea to what Uintatherium looked like. Although first named by Joseph Leidy in 1872, Uintatherium would become involved in the ‘bone wars’, a well-publicised feud between the palaeontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope. These two palaeontologists were constantly trying to outdo one another in terms of discoveries and the naming of new prehistoric animals, but often each would end up with the remains of the same type of animal, but each would give it their own name of choice and refuse to acknowledge the validity of the others name.

As far as Uintatherium is concerned Leidy was the first to name it, but both Marsh and Cope came into possession of further remains and subsequently provided their own names. Because both Marsh and Cope were both blinded by their desire to outdo one another, neither recognised the reality that they had described a creature that had already been named. As time progressed however, the true realisation of this mess was found by the wider palaeontological community, and Marsh’s and Cope’s names today exist only as synonyms to Uintatherium. One further element of confusion however is that a lot of species have been assigned to the Uintatherium genus in the past, partly because of this. Even further study has since found these species only represent a single species and while some of these are still very occasionally mentioned as recently as the early twenty-first century, only the type species of U. anceps is universally recognised by all. U. robustum is sometimes mentioned as valid, and an additional species, U. insperatus, is known from China.

Although Uintatherium is quite well known in terms of fossils, there continues to be uncertainty as to which mammals it is more closely related to. In terms of form Uintatherium is similar to a rhino, but it is not considered to be related because other primitive rhinos of the early and mid-Eocene were typically very small and different to the rhinos we know today. A recurring theory that is not widely accepted however is that Uintatherium, as well as the other dinoceratans, is related to the Anagaloidea group of mammals which are thought to be the ancestors of the lagomorphs (rabbits, hares) and rodents (mice, rats). Most however today consider Uintatherium to be an ungulate, or hoofed mammal, but exactly how it fits in to other ungulates is still not certain. Uintatherium will continue to be studied in the future, and possibly further discoveries of similar animals may yet help to provide further information for palaeontologists to work from.

The most instantly recognisable features of Uintatherium are the three pairs of horns that project upwards from on top of its head. The first pair were on the tip of the snout, the second between the eyes and the nostrils, and the third almost on the back of the skull. Palaeontologists are confident in ascertaining that these horns were for display in attracting mates as they are only present on the males. A further suggestion has been made that the horns may have been used in contests between two males in a similar manner to how male deer use their antlers. It is certainly feasible since a larger number of smaller horns would be more capable of locking with an opposing animal, and a mature and proven individual with possibly slightly larger horns would have an advantage over a younger and less well developed individual.

A further sign of sexual dimorphism are the enlarged upper canine teeth which appear to have been larger in the males, something that has led some to the conclusion that Uintatherium males may have bitten each other in dominance contests, although it’s possible that it could have been additional display. In life these enlarged teeth are thought to have been used in feeding, either for rooting up buried plant parts, or perhaps even for pulling out large amounts of aquatic plants. The other teeth in the mouth were relatively small and not suited for processing tough vegetation, something which implies that Uintatherium had to specialise in eating soft vegetation that could have been eaten without extensive processing in the mouth. One interesting feature about Uintatherium is that it had a concave skull, which means that it dipped inwards instead of outwards like in most other animals. Combined with the thick walls of the skull, this would have reduced the cranial cavity that resulted in a smaller brain size. By today’s standards of mammalian intelligence, Uintatherium didn’t even come close, and was probably restricted to certain set patterns of behaviour. However Uintatherium like other animals would only need to be intelligent enough to adapt to its environment, and with a temporal range of approximately fifteen million years, it was more successful than many other animals in this.

As the Eocene period progressed, large brontotheres such as Megacerops and primitive rhinos like Metamynodon began to appear on the landscape. In time these similar herbivores seem to have displaced dinoceratans like Uintatherium from their ecological niche, as so far no remains of Uintatherium have been found in late Eocene deposits.

Further Reading

– The problem of the Uintatherium molars. – Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History ; v. 48, article 18. – Horace Elmer Wood – 1923. – A Skull of Uintatherium from Henan – Vertebrata Palasiatica XIX (3): 208–214. – Yongsheng Tong & Wang Jingwen – 1981.