In Depth

When it comes to popularity Triceratops is only eclipsed by Tyrannosaurus, and even then there are a considerable portion of people who actually prefer Triceratops over the aforementioned apex predator. Yet despite its frequent depiction from toys to dinosaur books, films and other media, there is still a lot of controversy and misconception surrounding this much loved dinosaur.How Triceratops looked in life

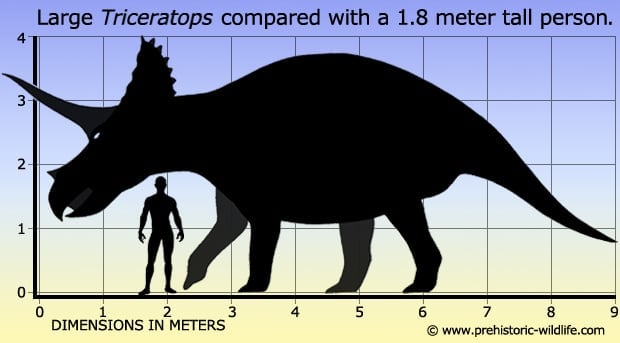

Triceratops is one of the few dinosaurs that hardly need a description. Like with other large ceratopsian dinosaurs it was a quadrupedal (four legged) herbivore that had a proportionately large skull in relation to its total body size, just under a third of the total length. The skull was adorned with a short neck frill that rose up from the back, and three horns. The largest horns were the two that rose up from above the eyes and reached up to one meter long, while the nasal horn that pointed up from the snout was much smaller. Some specimens of Triceratops sometimes have epoccipitals (small pointed bones) that are attached to the edge of the frill. Triceratops was once classed as a centrosaurine ceratopsian dinosaur because of this small frill, but today it is considered to be a chasmosaurine (often alternatively referred to as ceratopsine) on the basis of the well-developed brow horns that are usually greatly reduced or absent in centrosaurines. The frill itself is still interesting because its short and solid which makes it very different from other known genera that usually have long frills with holes in them. However this feature may yet have greater ramifications for Triceratops and some other ceratopsian dinosaur genera (click to skip down to this).

Like with other ceratopsian dinosaurs there has been some confusion as to how Triceratops stood and walked. Earlier reconstructions took into account the large skulls with the idea that the fore legs would have to sprawl out to the sides to support the bulk. Track ways suggested different however, that the fore legs were not sprawled which led to the question of ‘did Triceratops have sprawling or upright legs?’. The simple answer is a little of both as modern reconstructions including computer modelling have revealed that the fore legs were upright but with the elbows bowed out to the sides.

Another interesting feature is the way the fore feet (equivalent to your hands) rested on the ground. Unlike thereophorans (stegosaurs and ankylosaurs) and sauropods (quadrupedal long necked dinosaurs) the fingers pointed out to the sides rather than facing forwards. Although a primitive trait this actually reveals that the direct ancestors of the large late Cretaceous ceratopsian dinosaurs were actually bipedal (walked upon two legs) with their hands more for grasping and support rather than weight bearing.

One of the most exciting discoveries associated with Triceratops is a skin impression which also reveals the presence of bristle like fibres. Although this may appear strange, especially to those who have grown up with images of Triceratops being a relatively smooth skinned creature, earlier ceratopsians are thought to have had bristle like extensions on areas like the tail. This has been confirmed by some fossils from China and is especially poignant considering that the popular consensus is that primitive ceratopsian dinosaurs first appeared here towards the end of the Jurassic period. If these bristle structures were indeed present upon Triceratops, then it’s also plausible that other ceratopsian dinosaur genera between it and the primitive forms may have also had them.Ecological niche

The large number of Triceratops remains has led to speculation that this dinosaur was the dominant herbivore of Late Cretaceous North America. Other plant eating dinosaurs did exist however, including the much smaller ceratopsian Leptoceratops. Triceratops would have been a browser of low growing vegetation although there has been speculation that it may have brought down larger plants to feed up vegetation that would otherwise have been out of reach. Although destructive, this would have been quite an easy feat for such a large and presumably heavy animal.

The front of the mouth was arranged in the form of a beak, although the idea that it was used to shear off plant parts has fallen out of favour with most considering that it was most likely used for gripping and pulling. The teeth at the back of the mouth were arranged in shearing batteries. Like with other dinosaurs (including meat eaters) there were always replacement teeth growing in columns beneath the tooth that was exposed and processing food in the mouth. Once a tooth had become damaged or worn, the one beneath it would push it out and replace it, eventually being replaced itself when it to became worn. This constant replacement is why dinosaur teeth are some of the most common fossils available to buy on the market.

Because of its large size Triceratops would have been fairly safe from attack by the smaller predators of the time such as Troodon. Therefore the only creatures that could feasibly be a threat to it were equally large predators such as Tyrannosaurus and Albertosaurus, although even these would have probably preferred to take a smaller juvenile or a sick or injured individual that could not defend themselves as easily.Behaviour and social interaction

The features that Triceratops is most famous for are the horns and frill, as well as the possibility that they may have been weapons so that rather than running away from predators it could hold its ground and fight. Although this is by far the most popular notion it is not actually universally accepted amongst palaeontologists as the sole reason. The problem comes from the fact that while all ceratopsians have neck frills, and many of them had horns as well, they were very different amongst different genera. Logic would dictate that if they were just for fighting predators, the design would become standardised to its most effective form.

There is but one theory that explains the variance in frill shapes and horns: display. By having different frill and head shapes a certain genus of ceratopsian dinosaur could identify others of its species rather than get confused and try to mate with a different species. Many frills also bear the impressions of blood vessels that may have allowed Triceratops and other ceratopsian dinosaurs to flush blood into the soft tissue that covered their bony frills to produce vivid colour displays. The horns may have still been used in fighting, but rather than goring an attacking predator, they may have been locked with a rival Triceratops in a form of ‘fencing’. Holes in some Triceratops frills have been interpreted as being caused by the points of another Triceratops, and while alternative interpretations have suggested that they may have been caused by a parasitic infection or disease, further study has found them to be quite localised and unlikely to be caused by the randomness of an ailment. As such while the potential of the horns being turned against a predator is there, the horns were more likely used for display and intraspecific combat with rivals.

Triceratops has been frequently depicted as being a herding animal despite the fact that to date there is no definitive evidence to prove this. Other ceratopsians such as Centrosaurus and Styracosaurus have been found in bone beds that number hundreds of individuals which has been taken to some to be a sign of living in herds (although there are alternative arguments to this idea). With a noted exception of three juvenile Triceratops being found together all other remains seem to have come from solitary individuals. Another thing to consider against the large herd idea is the fact that Triceratops were not small creatures, and would have needed a substantial amount of plant matter to fuel their bodies. Multiply this by several hundred individuals in a herd and it’s easy to appreciate that Triceratops would have had a massive impact upon the ecosystems of Late Cretaceous North America.

However the idea that Triceratops lived mostly solitary lives is also unlikely when you look at the evidence and think about ecosystems in general. First is that Triceratops appears to have been the most common ceratopsian, and possible even most common large herbivorous dinosaur during the Late Cretaceous of North America which would suggest that Triceratops frequently stumbled upon one another in their travels. Second is that the largest herbivores today such as elephants can be seen to travel in both groups (of females and juveniles) and singles (mature males). Finally is the recognition that large predatory dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus were potentially capable of taking down a fully grown Triceratops, but would themselves have a near impossible time of attacking a group of Triceratops that had clustered together for defence.

It is not inconceivable that Triceratops may have formed small groups perhaps where a harem of females were watched over by a single male that held dominance over a group. Periodically roaming males may have challenged this male for control of the harem, using their frills and horns to gesture and display their strength to each other, perhaps even locking horns and fighting. The dominant male would win the right to mate with the harem females and pass on its genes, while the loser would have to wander alone where it would also be at greater risk of attack from predators. This is of course speculation, but this and similar systems can be observed in other animals today.Early discovery and the many species of Triceratops

Triceratops was actually first named as Bison alticornis because Othniel Charles Marsh thought that he was dealing with a Pliocene era species of Bison. Two years later with the advent of more fossils including a more complete skull, Marsh created the genus Triceratops. The horns referred to as Bison alticornis were referred to the earlier Ceratops genus that had also been established by Marsh, but later these too would be included with Triceratops.

Throughout the twentieth century more and more remains of Triceratops were recovered to the point where the genus became one of the most common ceratopsian dinosaurs from North America. However many of these remains showed variation between the skulls of individuals which led to the establishment of lots of species to the genus. Towards the end of the twentieth century however, palaeontologists had grown suspicious over the validity of these species and a 1986 paper by Ostrom and Wellnhofer concluded that only the type species of T. horridus was valid. The popular notion was that the variations between skull specimens were all down to individual variation as well as distortion during preservation (remembering that fossils are often formed during exposure to immense subterranean pressures).

Later study by Catherine Forster found clear difference between T. horridus and T. prorsus, as well as another species T. hatcheri being a different genus that was named Nedoceratops (as Nedoceratops hatcheri based from the original species). Although the differences have been taken to represent possible sexual dimorphism, palaeontologists Denver Fowler and John Scannella have noted that while these two species have been found in the same locations as one another, they are found in different levels of strata. This means that they were active at different times to one another and are therefore more likely to be different species.

Other ceratopsian genera such as Ojoceratops, Eotriceratops and Tatankaceratops amongst others have been assigned by some palaeontologists as potential synonyms to Triceratops. This is dubiously accepted as not all palaeontologists are in agreement to the validity of these genera, although most famous and controversial is the theory regarding the connection of Triceratops to Torosaurus.The Triceratops/Torosaurus debate

In 2010 news channels on the internet as well as some printed newspapers were abuzz with a newly proposed theory that was put forward by John Scannella (first proposed in 2009) which stated that Triceratops was the same as another dinosaur named Torosaurus. Although most reported on the facts of the case, but some news sources that couldn’t be bothered with accurate reporting decided to over sensationalise the story with headlines such as ‘Triceratops never existed’ and ‘Triceratops not real’.

The theory that was co-authored by the palaeontologist Jack Horner is relatively simple to understand. Triceratops and Torosaurus are both known from many of the same fossils sites as one another (although there are some exceptions), and from the same time periods. Triceratops has a short solid frill that is unusual for such a large ceratopsian dinosaur, especially an adult. Torosaurus has a more standard frill which is elongated and has fenestrae (holes) to reduce the weight of the growth. The conclusion is therefore that the skulls named as Triceratops represent the juvenile form, while the Torosaurus skulls represent the mature adult form of the same horned dinosaur.

Needless to say this is a very controversial proposal but one that is grounded in a lot of research and observational study of available fossils. The first thing that needs to be considered is that fact that ceratopsian dinosaur frills are made up of what is called metaplastic bone which changes in shape and form as the dinosaur reaches maturity. Another fact is that genera of ceratopsian dinosaurs which are known by both juvenile and mature adult forms all indicate that juveniles have shorter solid frills that develop into larger and longer frills with fenestra in later life. This is the key point in that as far as Triceratops is concerned if adults only had a short solid frill then the genus would actually be the exception to other known forms. An extension of the theory concerns sexual dimorphism, were the solid short frilled skulls are of females and immature males, and the large frilled skulls are of mature males that developed the frill to display to and attract females.

Other palaeontologists have so far had a hard time accepting this theory however, with one of the better documented arguments against coming from Andrew A. Farke in 2011. As part of the original theory Scannella and Horner not only proposed that Torosaurus was a synonym to Triceratops but another genus named Nedoceratops was also a synonym. Additionally they suggested that the single skull that had been attributed to Nedoceratops had a skull that was intermediate in development of the shorter Triceratops form, and the larger fenestrated Torosaurus form. Farke however in a re-study of the Nedoceratops remains not only concluded that the skull represented a single genus, but that the theory that Triceratops skulls could morph into Torosaurus skulls with age was simply unknown amongst ceratopsians as too much change was required.

A more recent report (at least at the time of writing) is a 2012 study by Daniel Field and Nicholas Longrich of Yale University. Field and Longrich studied thirty-five specimens and found that the skulls represented juvenile Torosaurus and mature Triceratops, and that there is a distinct lack of transitional forms that show a short frilled Triceratops maturing into a long frilled Torosaurus. Field and Longrich have acknowledged the existence of fossils that have been interpreted as being transitional forms, but explained them as being the products being caused by other factors. It has also been noted again that there are some locations where only one of the genera have been found, although this neither supports nor disproves the theory that Triceratops and Torosaurus are the same. Scannella has responded in news reports that this study does not disprove the idea that Triceratops and Torosaurus are the same, again citing fossils that could be seen as being transitional.

What this all comes down to is a matter of interpretation of the fossils by different individuals who all have their own ideas. The history of palaeontology has seen many theories developed by individual interpretations, some being confirmed by future discoveries and techniques, some being completely discredited. With a large amount of Triceratops and Torosaurus remains being known and presumably many more waiting to be dug from the ground, it may be only a matter of time before this theory is conclusively proven one way or the other. Other palaeontologists have been more cautious in their approach on the subject, but continue to watch and study the proceedings intensely to take on board future developments.

Regardless, of what may happen in the future, Triceratops will not cease to exist for one simple reason. Triceratops was named as a genus in 1889, while Torosaurus was not named until 1891. Under international rules governing the naming of animals, the first name always has priority over any subsequent naming. This famously happened with Brontosaurus and Apatosaurus, the former being raised in popular culture despite palaeontologists of the time already treating it as a synonym to Apatosaurus. The only chance that an exception could be made for this is if it can be proven that Triceratops has rarely appeared in print while Torosaurus was the vastly better known dinosaur, which quite frankly would be impossible to establish since most people do actually know what a Triceratops actually is, but would probably draw a blank when asked about a Torosaurus.

Further Reading

– Notice of new fossil mammals – American Journal of Science 34: 323–331 – Othniel Charles Marsh – 1887. – A new family of horned Dinosauria, from the Cretaceous – American Journal of Science 36: 477–478 – Othniel Charles Marsh – 1888. – Notice of new American Dinosauria – American Journal of Science 37: 331–336 – Othniel Charles Marsh – 1889a. – Notice of gigantic horned Dinosauria from the Cretaceous – Othniel Charles Marsh – 1889b. – Mounted skeleton of Triceratops prorsus in the Science Museum – Scientific Publications of the Science Museum 1: 1–16 – B. R. Erisckdon – 1966. – The behavioral significance of frill and horn morphology in ceratopsian dinosaurs – Evolution 29 (2) – J. O. Farlow & P. Dodson – 1975. – Mechanics of posture and gait of some large dinosaurs – Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 83: 1–25 – R. M. Alexander – 1985. – The Munich specimen of Triceratops with a revision of the genus – Zitteliana 14: 111–158 – J. H. Ostrom & P. Wellnhofer – 1986. – Late Maastrichtian paleoenvironments and dinosaur biogeography in the Western Interior of North America – Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology and Palaeoecology 60 (3): 290 – T. M. Lehman – 1987. – The cranial morphology and systematics of Triceratops, with a preliminary analysis of ceratopsian phylogeny. – Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. 227 pp. – C. A. Forster – 1990. – Bite marks attributable to Tyrannosaurus rex: preliminary description and implications – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 16 (1): 175–178. – G. M. Erickson & K. H. Olsen – 1996. – Species resolution in Triceratops: cladistic and morphometric approaches – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology – C. A. Forster – 1996. – Limb bone scaling, limb proportions, and bone strength in neoceratopsian dinosaurs – Gaia 16: 13–29 – P. Christiansen & G. S. Paul – 2001. – Horn Use in Triceratops (Dinosauria: Ceratopsidae): Testing Behavioral Hypotheses Using Scale Models – Palaeo-electronica 7 (1): 1–10 – A. A. Farke – 2004. – The smallest known Triceratops skull: new observations on ceratopsid cranial anatomy and ontogeny – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26 (1) – M. B. Goodwin, W. A. Clemens, J. R. Horner & K. Padian – 2006. – Evidence of Combat in Triceratops – In Paul Sereno. PLoS ONE 4 (1) – A. A. Farke, E. D. S. Wolfe, D. H. Tanke & P. Sereno – 2009. – The first Triceratops bonebed and its implications for gregarious behavior – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29 (1): 286–290 – Joshua C. Mathews, Stephen L. Brusatte, Scott A. Williams & Michael D. Henderson – 2009. – Triceratops and Torosaurus dinosaurs ‘two species, not one – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29 (4): 1136–1147 – S. -I. Fujiwara – 2009. – Anagenesis in Triceratops: evidence from a newly resolved stratigraphic framework for the Hell Creek Formation – 9th North American Paleontological Convention Abstracts. Cincinnati Museum Center Scientific Contributions 3. Pp. 148–149 – J. B. Scanella & D. W. Fowler – 2009. – Torosaurus Marsh, 1891, is Triceratops Marsh, 1889 (Ceratopsidae: Chasmosaurinae): synonymy through ontogeny – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30 (4): 1157–1168 – J. Scannella & J. R. Horner – 2010. – Ontogeny of the parietal frill of Triceratops: a preliminary histological analysis – Comptes Rendus Palevol 10: 439–452 – J. R. Horner & E. Lamm – 2011. – Torosaurus Is Not Triceratops: Ontogeny in Chasmosaurine Ceratopsids as a Case Study in Dinosaur Taxonomy – PLoS ONE 7(2) – N. R. Longrich & D. J. Field – 2012. – Evolutionary trends in Triceratops from the Hell Creek Formation, Montana. – Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (28): 10245–10250. – John B. Scannella, Denver W. Fowler, Mark B. Goodwin & John R. Horner – 2014.