In Depth

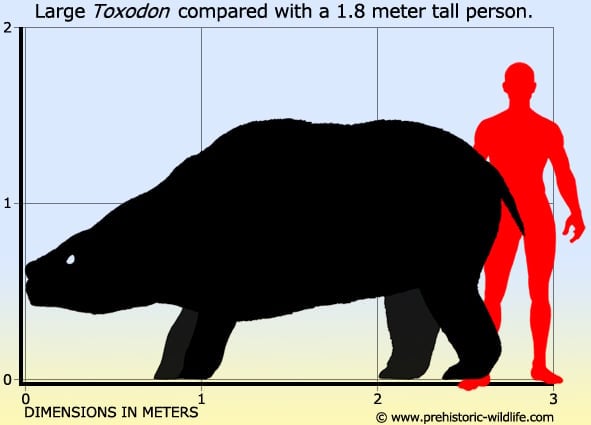

Toxodon was a large herbivorous mammal that was similar in proportion to a rhinoceros, but also possessed other features that were similar to hippopotamuses and possibly even elephants. The post cranial skeleton has a very robust construction which suggests that in life Toxodon was a very heavy animal. The feet were plantigrade which means that Toxodon walked with the flat of its foot so that it could better support its body weight. The body was wide which suggests that Toxodon had an extensive digestive system for processing plant matter. The hind legs were much longer than the fore legs which meant that the main body sloped down towards the front. This also meant that the head was carried closer to the ground where Toxodon could feed upon low growing vegetation. The neural spines of the anterior dorsal vertebrae were enlarged, either providing anchor points for neck muscles that supported the heavy skull, or supported the formation of a fatty hump that served as storage for leaner times.

Toxodon has been envisioned as both a grazer, an animal that eats grasses, and as a browser, an animal that feeds on the foliage of shrubs and low growing trees. It’s quite possible that Toxodon was a generalist that did both as the wide mouth could have easily been used to do either method. Although so far not known for certain, some researchers have considered the possibility that Toxodon had a prehensile lip. This could have been used to guide vegetation into the mouth, allowing Toxodon to adapt to whatever was available.

Many reconstructions of Toxodon have seen it set as a semi aquatic animal similar to hippo that submerged itself in water to support the bulk of its body while feeding upon aquatic plants. However since the twentieth century this has been considered an antiquated view that gives a false representation of the habitats that Toxodon frequented. First and most obvious is that Toxodon remains have always been found in arid ecosystems, something to be expected since most of South America was covered by steppe and grassy plains during the Pleistocene. Additionally an animal that has its head carried low on its body would not be able to completely submerge itself otherwise it would not be able to get its head above the water to breathe, which means that Toxodon could not have tried to use water to support its weight for risk of drowning. During the Pleistocene Toxodon seems to have been one of the most common herbivores across South America, and lived at the time of the Great American Interchange. This is where the formation of the Isthmus of Panama created a land bridge that joined North and South America, allowing previously isolated animals to intermix and spread out into new locations. As such Toxodon probably did not have to worry about being attacked by phorusrhacids, popularly known as terror birds, since they were largely extinct by the time it appeared. Unfortunately however this extinction seems to have been brought about by the spread of North American predators such as the sabre toothed cat Smilodon. North American populations of Smilodon seem to have had a preference for hunting large bison, and it’s not inconceivable that some may have adapted to killing Toxodon.

The final nail in the proverbial coffin however seems to have been the arrival of human hunters. Arrowheads found with Toxodon remains virtually prove that this was a prey animal for early human hunters, and the theory of overkill of Toxodon populations has been repeatedly used to explain the disappearance of much of the megafauna animals at the end of the Pleistocene. However while hunting would have certainly been a contributing factor to their extinction, there are other theories such as on-going climate change, diseases and even comets exploding in the air above the planet (similar to the 1908 Tunguska event but on a larger scale) that have been proposed to explain the disappearance of the megafauna.

Further Reading

. – ESR dating of a Toxodon tooth from a Brazilian karstic cave. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 52 (5): 1345–1349. – O. Baffa, A. Brunetti, I. Karmann & C. M. Dias Neto – 2000. – Microstructural defects and enamel hypoplasia in teeth of Toxodon Owen, 1837 from the Pleistocene of Southern Brazil. – Lethaia. 47 (3): 418–431. – P. R. Braunn, A. M. Ribeiro & J. Ferigolo – 2014. – Ancient proteins resolve the evolutionary history of Darwin’s South American ungulates. – Nature. 522 (7554): 81–4. – Welker, Frido; Collins, Matthew J.; Thomas, Jessica A.; Wadsley, Marc; Brace, Selina; Cappellini, Enrico; Turvey, Samuel T.; Reguero, Marcelo; Gelfo, Javier N.; Kramarz, Alejandro; Burger, Joachim; Thomas-Oates, Jane; Ashford, David A.; Ashton, Peter D.; Rowsell, Keri; Porter, Duncan M.; Kessler, Benedikt; Fischer, Roman; Baessmann, Carsten; Kaspar, Stephanie Olsen, Jesper V.; Kiley, Patrick; Elliott, James A.; Kelstrup, Christian D.; Mullin, Victoria; Hofreiter, Michael; Willerslev, Eske; Hublin, Jean-Jacques; Orlando, Ludovic; Barnes, Ian; Macphee, Ross D. E. – 2015. – Ancient collagen reveals evolutionary history of the endemic South American ‘ungulates’. – Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 282 (1806): 20142671. – M. Buckley – 2015. – Isotopic paleoecology (δ13C, δ18O) of Late Quaternary megafauna from Mato Grosso do Sul and Bahia States, Brazil. Quaternary Science Reviews. 221: 105864. – T. R. Pansani, F. P. Muniz, A. Cherkinsky, M. L. Pacheco & M. A. Dantas – 2019.