Discovery & Reconstruction

Spinosaurus as we know it today did not begin to come into existence until the 1990’s, something that is quite surprising when you think that it was first described in 1915.

The reason for this is that there has been no choice but to study only the most partial of remains, a study that was frustrated even further in World War Two when the Munich museum which housed the first Spinosaurus remains was destroyed by a bombing raid which also obliterated the Spinosaurus holotype specimens.

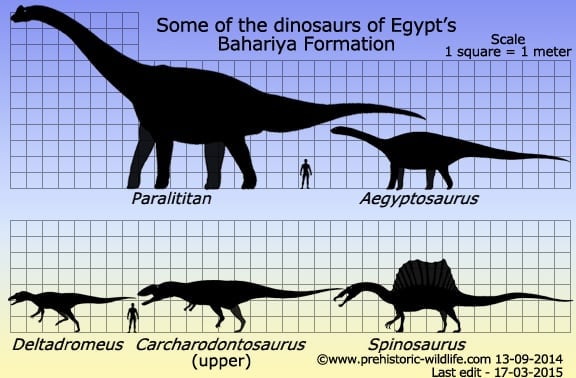

The holotype was a collection of partial remains that were recovered from the Bahariya Formation of Egypt in 1912. These remains included a small number of ribs, gastralia (belly ribs), vertebrae, teeth, dentaries (the part of the lower jaw that holds the teeth) left maxilla and of course some of the now famous neural spines. This material was enough to convince Stromer that he was dealing with a new theropod dinosaur, but the unprecedented nature of the find combined with the understanding of the day still resulted in an inaccurate first reconstruction.

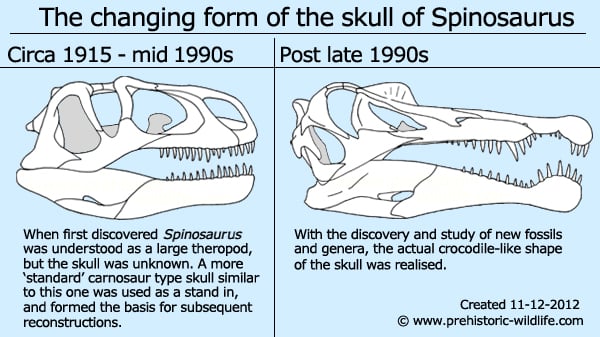

The main area of fault was the skull in that due to the lack of good skull material Spinosaurus was given a more classic carnosaur skull that resembled something like that of an Allosaurus. Also further material attributed to Spinosaurus by Stromer in 1934 now appears to have belonged to another theropod such as Carcharodontosaurus that was active in North Africa around the same time as Spinosaurus.

However in his defence Stromer did consider the new material of hind limbs and vertebrae to belong to something else which is why he named the specimens ‘Spinosaurus B’.

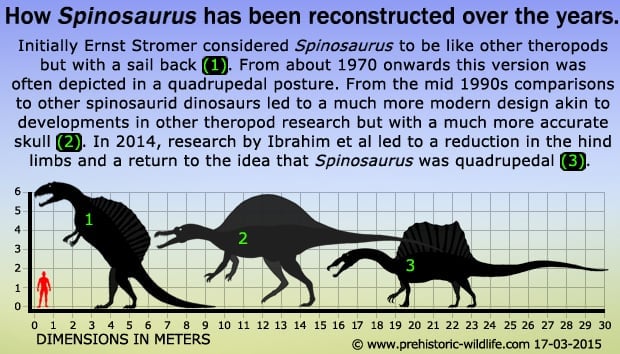

For the largest part of the twentieth century Spinosaurus was frequently depicted in dinosaur books as a sail backed carnosaur that if it were not for the sail would be like any other large theropod.

This depiction also existed well into the first decade of the twenty-first century despite new discoveries proving otherwise. While usually depicted as a bipedal predator, this version of Spinosaurus has also been envisioned as a quadrupedal one, particularly in the 1970s and 1980s.

New Spinosaurus material of vertebrae and partial dentaries from the Kem Kem Beds of Morocco were described by Dale Russel in 1996, but it was a partial snout described by Russel and Torquet in 1998 that hinted at the real nature of Spinosaurus.

This new material combined with drawings of the Spinosaurus holotype specimen allowed for the material to be compared to two other dinosaurs that were discovered late in the twentieth century.

In England in 1983 a dinosaur was found that would be named Baryonyx in 1986, and this was a theropod that had an unusual crocodile-like skull. Then in 1998 another new dinosaur was discovered in the Elrhaz Formation of Niger that was very similar to Baryonyx save for tall neural spines on its back vertebrae.

This dinosaur also had a crocodile like skull that resulted in it being named Suchomimus (crocodile mimic).

The comparison of the new Spinosaurus material was a comparatively easy one as even though the snout material was incomplete, it was so similar to Baryonyx and Suchomimus that it was almost certain that Spinosaurus was a similar type of dinosaur as these two.

Today Spinosaurus skeletons on display in museums are based upon these other two more complete dinosaurs with some changes worked in to reflect the slight differences in the known Spinosaurus material, new examples of which continue to be infrequently recovered from Africa.

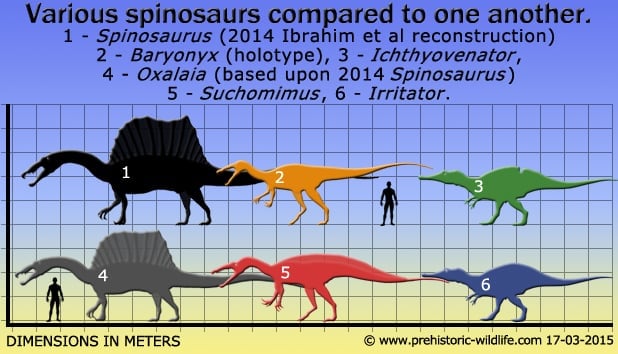

Today these dinosaurs all sit within their own group and since Spinosaurus was the first one named the group is called the Spinosauridae. Aside from Baryonyx and Suchomimus, Ichthyovenator is known from Laos, while others such as Irritator and Oxalaia are known from Brazil as well as other more dubious entries which may probably be synonymous with others. The fact that spinosaruids are known from Brazil and North Africa is also proof that the two continents were still joined by land bridges perhaps as late as the Early Cretaceous.

From the 1990s to 2014, Spinosaurus was commonly portrayed as a very long but comparatively lightly built theropod dinosaur, that aside from the skull and sail/hump on the back, was roughly similar to other large theropod dinosaurs in build. Then in September 2014 a new study written by Nizar Ibrahim, Paul C. Sereno, Cristiano Dal Sasso, Simone Maganuco, Matteo Fabbri, David M. Martill, Samir Zouhri, Nathan Myhrvold and Dawid A. Iurino, was published along with great fanfare by National Geographic including a full size model reconstruction. This ‘new’ Spinosaurus still had a crocodile-like skull and a sail on its back, but this time Spinosaurus had been rebuilt as an obligatory quadrupedal dinosaur.

This new reconstruction came about from the process of all the old confirmed Spinosaurus fossils being rebuilt three dimensionally in computer software, and then augmented with new fossil finds that had taken place over only a few years before.

The reconstruction was still missing several other pieces, but other spinosaurid dinosaurs were studied and by comparison scaled and added to fill the gaps where possible. The key difference between this reconstruction and older ones is that the legs in the 2014 Ibrahim et al reconstruction are significantly shorter than they were previously envisioned and unlikely to be capable of long term bipedal locomotion.

The pelvis was also noted as having a reduced size, meaning less attachment space for large leg muscles, and meaning that the rear legs were less able to support the weight of the body. Also, the researchers plotted the centre of gravity of the body and found that it was well forward from the hips, different from the overwhelming majority of other large theropods, and by extension meaning that Spinosaurus would have had to support its body with its arms when on land.

The ‘new 2014’ Spinosaurus quickly filled the internet with news stories not only because it was so different from before but because for at least twenty years before Spinosaurus had fast become one of the more popular dinosaurs in fiction such as films and games.

However many have questioned the accuracy of the Ibrahim et al reconstruction. The key problem that most people have is that this reconstruction is a composite made up of numerous Spinosaurus individuals as well as missing pieces filled in by comparison to other spinosaurid dinosaurs, with some even going so far as to state that the new reconstruction is only a ‘chimera’ and cannot be validated without a substantially more complete specimen of Spinosaurus, though as history tells us, that so far has been exceedingly frustrating to find.

The other main issue that some people have is the size of the rear legs, notably from the vast reduction in size to what they have been used to seeing.

This begs the question however, if Spinosaurus did have notably small hind limbs, then what about other spinosaurid theropods? At the time of writing the only two spinosaurid genera known to have reasonably complete hind limb remains are Baryonyx and Suchomimus (sometimes considered by some to be synonymous with Baryonyx), which seem to be closer to other more classic theropod leg proportions.

However, both of these are thought to be based upon juvenile and subadult individuals respectively, so could it be that younger spinosaurids had proportionately long legs that reduced in length as they reached adulthood.

A certain body part not growing at the same rate as the rest of the body is actually very common, and the precedent of leg length proportions reducing with age in large theropod dinosaurs does exist, and is particularly observable in some of the large tyrannosaurs. In Albertosaurus for example, a genus where most of the life stages are known, there is a clearly observable trend where as individuals get older, larger and specifically heavier, the length of the hind limbs significantly shortens.

Another idea for shorter legs in Spinosaurus than other spinosaurids could be that Spinosaurus simply represents a more advanced and hence more specialised form. So far Baryonyx is only known from the earlier stages of the Early Cretaceous, and Suchomimus slightly later in the Aptian stage of the Cretaceous.

Spinosaurus fossils however range between the last stage of the Early Cretaceous, the Albian, to the first stage of the Late Cretaceous, the Cenomanian. This means that Spinosaurus would have had many millions of years more opportunity to develop and stabilise a reduction in the rear legs.

As a genus though Spinosaurus has always been in a state of flux, and we may yet only be one more discovery away from having to do yet another revision to how we reconstruct this dinosaur.

Tail reconstruction

In 2020 a new paper by Ibrahim et al was published, this time describing an almost complete tail of a Spinosaurus.

The vertebrae of this tail showed highly developed neural spines as well as deep chevrons on the underside. These extended features applied to all of the vertebrae right down to the end of the tail, making the whole tail into a broad paddle shape.

Furthermore, the tail of Spinosaurus was not stiff, it was actually very flexible and capable of a lateral, side to side movement. This means than in theory Spinosaurus could have propelled itself through the water with its tail.

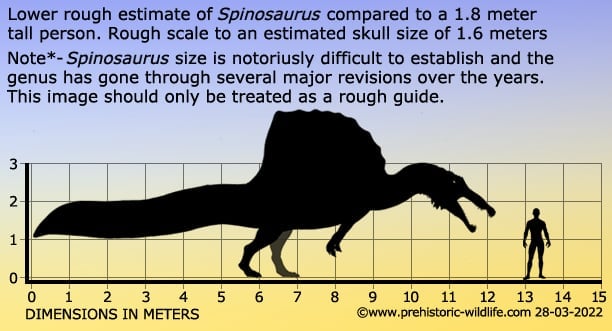

Estimating the size of Spinosaurus

Spinosaurus is now often regarded as the biggest known meat eating theropod dinosaur (herbivores like large sauropods were of course bigger), however the actual size is really just an estimate extrapolated from an educated guess.

What is clear is that Spinosaurus was a very large animal but herein lies the problem as the larger animals get, the less complete their remains tend to be because it takes so much more material to bury them and protect the body from scavengers and as well as the full ravages of nature.

The more an animal is exposed upon death means the less complete long term remains like fossils will be.

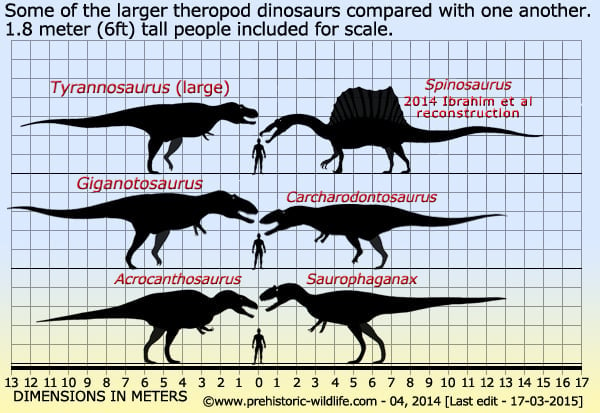

Still with a smaller estimate of just over twelve and a half meters, Spinosaurus would have been comparable to Tyrannosaurus, and only just smaller than Giganotosaurus (it needs to be remembered that even though Giganotosaurus has a size estimate of thirteen meters, it would still only be marginally larger than the largest known Tyrannosaurus).

Comparison to other smaller spinosaurids that were consequently scaled up to the same size as the Spinosaurus material points to sizes that approach the larger length estimate as indeed being possible. For the time being at least, Spinosaurus is likely to remain the longest theropod.

Length however is but one measure of size, and often it is not the length of the animal that is important but the weight. Gauging the weight of an animal from bones is considerably more difficult that just measuring the length because so many factors need to be considered.

Different kinds of tissue can be denser than others resulting in different weights even though they take up the same space (for example muscle weighs more that fatty tissue). You also need to look at how the tissue is distributed as many ‘larger’ animals are often only large when viewed from one angle and can be very thin in their actual build.

The lifestyle of Spinosaurus

Although Spinosaurus had been a mainstay of dinosaur books since as early as the 1970’s, the wider public were not introduced to its current form until the release of the 2001 film Jurassic Park III. In both this film and earlier depictions where is had a more ‘classic’ theropod skull, Spinosaurus was a predator larger and more fearsome than even a Tyrannosaurus rex, and would spend its time chasing and killing other dinosaurs like Ouranosaurus.

The reality however may in fact be very different. To reveal the nature of Spinosaurus, you first need to look at the skull elements, not only the most well-known parts but it’s the skull that often gives the best indication of lifestyle for any predator.

Usually theropods have relatively short and high snouts to house such body parts as biting muscles and nasal cavities so that they can hunt by scent. Spinosaurus however had a comparatively long and narrow snout like a crocodile.

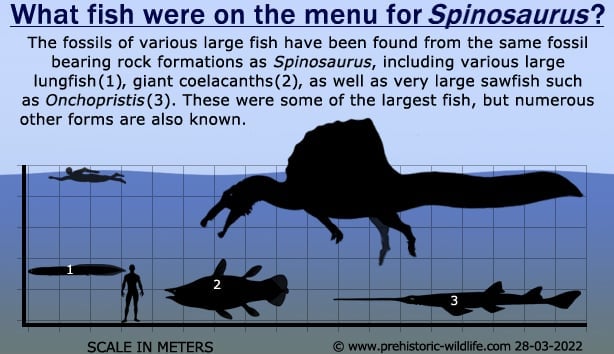

The tip of the snout has a recessed dip in the premaxilla which the tip of the rounded lower jaw matches and fits into. This adaptation is seen in some other animals such as crocodiles and serves to increase grip upon smaller prey, particularly slippery prey such as fish.

The teeth of Spinosaurus are neither serrated and flattened for slicing, or strongly built for crunching bone. They are however narrow, sharp and numerous like they are sometimes seen in crocodiles as well as piscivorous fish eating pterosaurs.

The arrangement of the forward teeth of the upper jaw is such that the largest are on either sides of the premaxilla notch and point towards the rounded tip of the lower jaw. The teeth on this rounded lower jaw tip point upwards into the curvature of the snout notch.

Oxygen isotope analysis of Spinosaurus teeth has also revealed that they were exposed to aquatic environments for long periods.

Another further special adaptation are the nostrils which are high up just in front of the eyes.

This is very unusual in itself for a carnivorous animal because as an unofficial rule carnivores have their nostrils in the front of their snouts, to not only allow for scents to be more accurately analysed through a larger nasal cavity, but also to easily smell the meat that they are eating. The fact that the nostrils are so high strongly suggests that the more usual placement was not possible due to how Spinosaurus lived and behaved.

A 2009 study by C. Dal Sasso, S. Maganuco and A Cioffi focused upon what were small passages called foramina that lead towards the same cavity inside the snout. These are taken to have been pressure sensitive receptors that when dipped into the water revealed the motions of passing fish that created pressure waves as they swam through the water, allowing Spinosaurus to not only know when a fish was nearby, but when it would be at its closest for a strike.

All together these adaptations point to Spinosaurus being a very specialised predator that hunted for fish either from the side of rivers, to even getting into the river and swimming amongst the fish.

The long and narrow snout meant that Spinosaurus could dip its pressure sensitive nose into the water while having a large area for surface capture. The higher nostrils meant that Spinosaurus could comfortably breathe while its snout was dipped in the water, although a possible weakness here could be a reduced nasal cavity that meant Spinosaurus could not process smells as well as other large theropods that had larger nasal cavities, though as a fish hunter, Spinosaurus would have not needed a keen sense of smell anyway.

Because the teeth were angled to follow the contours of their opposite jaws they would have provided the maximum amount of available grip on a slippery and struggling fish.

One of the more accurate depictions of this lifestyle was in the 2011 BBC series Planet Dinosaur, which depicted Spinosaurus as a large and specialised carnivore that primarily focused upon hunting fish like Onchopristis, yet would also supplement its diet by scavenging carrion.

It should be remembered that as a meat-eater Spinosaurus would not have passed up the opportunity for a free meal, perhaps using its more massive size to intimidate smaller theropods like Rugops, or even terrestrial crocodiles like Kaprosuchus from a carcass. If active at the same time as one another then Spinosaurus may have even gone after the kills of giant crocodiles like Sarcosuchus which would have been living in the same ecosystem.

The 2014 reconstruction of Spinosaurus by Ibrahim et al also supported the idea that Spinosaurus would readily enter the water and actually swim about. Not only did they cover isotope analysis which confirmed a great deal of exposure to aquatic environments, they also noted that Spinosaurus had particularly dense bones.

This is a common feature in animals that spend a lot of time swimming in the water as the greater bone density helps the animal with buoyancy issues so that it can actually swim under the surface is necessary. Ibrahim et al also noted that the claws on the feet were flat-bottomed, which would be a further aid in pushing against the water while swimming. This also strongly suggests that the main swimming propulsion was provided by the rear legs.

The possibility also remains that Spinosaurus may have hunted land animals, although no fossil evidence is known that strongly supports this. In South America a pterosaur bone was found with a spinosaurid tooth stuck into it, and recovery of the related Baryonyx revealed the presence of Iguanodon bones inside of the area that its gut would have been. Still these may have been cases of scavenging rather than attempted hunting. Baryonyx also revealed the partially digested remains of the fish Lepidotes, further supporting the fish specialisation hypothesis.

Because Spinosaurus disappears from the fossil record well before the end of the dinosaurs sixty-five million years ago, it must have succumbed to something else other than the established extinction theories that ended the dinosaurs once and for all.

Perhaps the easiest explanation for its demise is that it simply became far too specialised, and when the ecosystem it was living in changed to be drier the rivers systems dried up, removing the prey source that Spinosaurus was best equipped to deal with. In the face of competition with more generalist theropods, Spinosaurus just could not compete with their success and was eventually driven to extinction.

Sail or hump, and more importantly why?

The key features of Spinosaurus are the high neural spines of the dorsal vertebrae that were the inspiration for the name, the largest of which of the original material was one hundred and sixty-five centimetres long.

The actual construction that resulted from these spines however is one of the key subjects of debate with the two main camps being ‘sail’ and ‘hump’ (a rare third is that the spines stuck out by themselves but the majority of palaeontologists consider this very unlikely).

A sail would have given Spinosaurus an appearance similar to the famous but much older Dimetrodon. The sail itself would have been a membrane of skin and thin tissue that would have been held high off the back for maximum exposure.

However the spines themselves seem incredibly strong and robust just for the purpose of supporting a skin sail, and this leads into the hump theory. A hump probably would not have been a very musculature structure but composed more of fatty tissues that may have been used for food storage as well as weighing less than the same proportionate amount of muscle.

The only thing that inspires even greater debate about whether Spinosaurus had a sail or hump is just what it was there for. Why did Spinosaurus have to be so different, not just from other theropods, but the other spinosaurids where the vertebrae are known to have much smaller neural spines.

Returning to the above theory of a hump of fatty tissue would suggest that the humps primary use would be store fat when Spinosaurus was able to gorge itself on a plentiful supply. Going with the fish specialisation, Spinosaurus’s prey may have been seasonal with fish swimming upstream to spawn, but being relatively sparse throughout the rest of the year.

Spinosaurus may have stored extra food as fat so that it could continue into the leaner times of the year where prey was less frequent when it may have had to supplement its diet by scavenging.

Fish would also probably not be constantly active in the same water system and Spinosaurus may have had travel quite a distance when searching for fish. This concept has also been proposed for Acrocanthosaurus, another theropod dinosaur with slightly enlarged neural spines that was active in the Aptian to Albian stages of North America.

This may have been an adaptation to the climate as Suchomimus which is also from North Africa had a similar but smaller growth on its back where as Baryonyx which is known from England did not have any neural spine growth at all (all though there is speculation that the Baryonyx holotype is of a juvenile dinosaur).

Another and more controversial theory is that of thermoregulation. By pumping blood up into either the sail or hump, Spinosaurus could expose its blood to the warmth of the sun’s rays increasing its body temperature so that it could become more active.

Also if too warm it may have relied upon a prevailing wind to cool its blood so that it did not overheat. The problem with this theory is that it automatically assumes that Spinosaurus was cold blooded and relied upon basking in the sun.

There have been many studies done that suggest dinosaurs were potentially warm-blooded even if the exact method was not identical to mammalian methods of maintaining a warm-blooded metabolism.

As a very large dinosaur Spinosaurus may have been subjected to the effects of gigantothermy where an animal is so massive that its own body insulates its internal parts from the outside cold.

An in between theory is that since Spinosaurus presumably spent a lot of time in the water waiting to strike at fish it may have been chilled by the very water it was standing in. By exposing its sail/hump to the sun it could possibly warm its blood enough to counter the waters cooling effect.

However this would not explain why others like Baryonyx and Suchomimus did not do the same, unless size of the animal is a determining factor. The idea that the hump was for thermoregulation is especially valid however if Spinosaurus spent a lot of time swimming in the river systems of Cretaceous North Africa.

The most popular theory, which is a failsafe option for any unknown growth, is that the sail/hump was for the purpose of display.

This would be a characteristic where the most complete, and possibly even the most colourful sail/hump was the best, and the individual it belonged to was more likely to pass on its genes to the next generation of Spinosaurus.

This could in part also connect with the fat hump theory in that a well fed Spinosaurus would have a larger and fatter hump that would show others of its kind how successful a predator it was, proving that it was more worthy of reproducing.

Further Reading

- – New remains of the enigmatic dinosaur Spinosaurus from the Cretaceous of Morocco and the affinities between Spinosaurus and Baryonyx. – Neues Jahrbuch f�r Geologie und Pal�ontologie, Monatshefte (2): 79–87. – E. Buffetaut – 1989.

- – Remarks on the Cretaceous theropod dinosaurs Spinosaurus and Baryonyx. – Neues Jahrbuch f�r Geologie und Pal�ontologie, Monatshefte (2): 88–96. – E. Buffetaut – 1992.

- – Neural spine elongation in dinosaurs: sailbacks or buffalo-backs? -. Journal of Paleontology 71 (6): 1124–1146. – J. B. Bailey – 1997.

- – A new specimen of Spinosaurus (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Lower Cretaceous of Tunisia, with remarks on the evolutionary history of the Spinosauridae. – Bulletin de la Soci�t� G�ologique de France 173 (5): 415–421. – E. Buffetaut & M. Ouaja – 2002.

- – Pterosaurs as part of a spinosaur diet. – Nature 430 (6995): 33. – E. Buffetaut, D. Martill & F. Escuilli� – 2004.

- – New information on the skull of the enigmatic theropod Spinosaurus, with remarks on its sizes and affinities. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25 (4): 888–896. – C. del Sasso, S. Maganuco, E. Buffetaut & M. A. Mendez – 2005.

- – New information regarding the holotype of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus Stromer, 1915. – Journal of Paleontology 80 (2): 400–406. – J. B. Smith, M. C. Lamanna, H. Mayr & K. J. Lacovara – 2006.

- – A neurovascular cavity within the snout of the predatory dinosaur Spinosaurus. – 1st International Congress on North African Vertebrate Palaeontology. Mus�um national d’Histoire naturelle. – C. Dal Sasso, S. Maganuco & A. Cioffi – 2009

- – Oxygen isotope evidence for semi-aquatic habits among spinosaurid theropods. – Geology 38 (2): 139–142. – R. Amiot, E. Buffetaut, C. L�cuyer, X. Wang, L. Boudad, Z. Ding, F. Fourel, S. Hutt, F. Martineau, A. Medeiros, J. Mo, L. Simon, V. Suteethorn, S. Sweetman, H. Tong, F. Zhang & Z. Zhou – 2010.

- – Fine sculptures on a tooth of Spinosaurus (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from Morocco. – Bulletin of Gunma Museum of Natural History 14: 11–20. – Y. Hasegawa, G. Tanaka, Y. Takakuwa & S. Koike – 2010.

- – Semiaquatic adaptations in a giant predatory dinosaur – Science vol. 345, no.6204 – Nizar Ibrahim, Paul C. Sereno, Cristiano Dal Sasso, Simone Maganuco, Matteo Fabbri, David M. Martill, Samir Zouhri, Nathan Myhrvold & Dawid A. Iurino – 2014.

- - A buoyancy, balance and stability challenge to the hypothesis of a semi-aquatic Spinosaurus Stromer, 1915 (Dinosauria: Theropoda). - PeerJ. 6: e5409. - D. M. Henderson - 2018.

- - Tail-propelled aquatic locomotion in a theropod dinosaur. - Nature. - Nizar Ibrahim, Simone Maganuco, Cristiano Dal Sasso, Matteo Fabbri, Marco Auditore, Gabriele Bindellini, David M. Martill, Samir Zouhri, Diego A. Mattarelli, David M. Unwin, Jasmina Wiemann, Davide Bonadonna, Ayoub Amane, Juliana Jakubczak, Ulrich Joger, George V. Lauder & Stephanie E. Pierce - 2020.

- – Sigilmassasaurus is Spinosaurus: a reappraisal of African spinosaurines. – Cretaceous Research. 114: 104520. – R. S. H. Symth, N. Ibrahim & D. M. Martilla – 2020.