In Depth

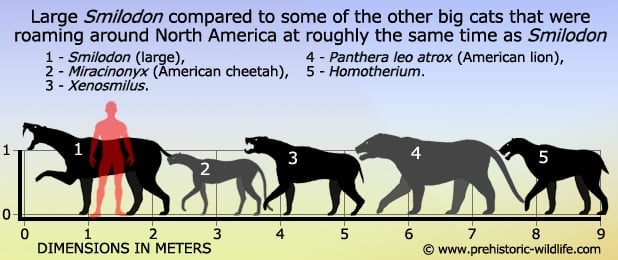

Whenever you hear someone mention a ‘Sabre Toothed Tiger’, what they are really talking about, whether they realise it themselves or not, is Smilodon. This is because Smilodon does not belong to the same cat family as Tigers, which belong to the Pantherinae group. As a member of the Machairodontinae, a more acceptable generic name for Smilodon is ‘Sabre toothed cat’.

This is not to be pedantic; it’s just about being factually correct so that people do not learn the wrong information.

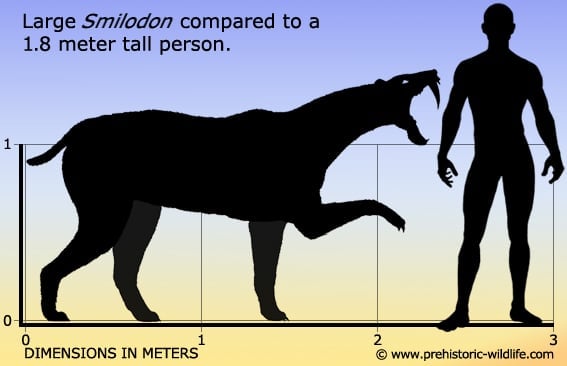

Smilodon has a very wide expanse in the fossil record with the earliest species S. gracilis being known from the early Pleistocene till the Ionian stage about five-hundred-thousand years ago. Not only is S. gracilis the earliest species of Smilodon, it is also the smallest with weight estimates between 55 to a 100Kg.

S. fatalis is more intermediate in size with estimates of 160-280Kg. Its entry in the fossil record incorporates the final three sixths of Smilodon’s temporal range 1.6 million years ago near the start of Calabrian, till the early Holocene ten-thousand years ago.

This overlaps the existence of S.gracilis by a little over one million years.

The largest and last species of Smilodon is S. populator, known in the fossil record from the upper part of the Calabrian till the early Holocene ten thousand years ago. Study of Smilodon remains also indicates that for a period of five-hundred-thousand years between the Calabrian and Ionian stages, all three species would have existed and been active at the same time as one another.

One interesting hunting theory is that Smilodon would lurk in the tree canopy waiting for a prey animal to walk underneath. Smilodon would then drop out of the trees and onto the animals back, sinking its teeth into it is neck before it even knew what had hit it.

This is especially plausible for S. gracilis, as if its size estimates of 55-100 Kg are correct, it would be in roughly the same weight class as a modern leopard, a big cat which is known to spend a lot of time in trees.

However, S. populator was a much larger species of Smilodon, and as such would need either larger or more prey. With maximum weight estimates approaching half a metric ton , its large weight would also restrict its ability to drop from the trees.

Although it may still have been able to drop from rocks which would be better able to support its weight, this still may have been a too passive method of hunting to support itself as a larger body would require more food to fuel it. For this reason it is highly likely it would at least on occasion switch to a different method of finding food.

Large numbers of Smilodon have been recovered from the La Brea tar pits in California. In fact the recovered remains are in the hundreds, with an unknown number still waiting to be found.

Smilodon would have been lured to this predator trap on the false promise of free food as other animals had become stuck and began struggling and calling out in distress. Many carnivorous animals, not just Smilodon, ended up getting stuck themselves as indicated by the vast numbers and types of remains.

This indicates that Smilodon like other predators was not above scavenging, either at La Brea or other locations. This does not mean that Smilodon was just a scavenger, in fact cats from the largest Tigers to the smallest domestic house cats are all active predators, which is why even well fed pets will still kill birds and bring them back to their owners.

While direct fossil evidence has not been found, Smilodon are sometimes envisioned as being pack hunters in a similar fashion to modern day lions.

Although perhaps not the fastest of runners, two or three Smilodon jumping upon a large prey item could have used their combined strength and body weights to wrestle their prey to the ground. Once restrained, one of the Smilodon would then be able to finish the prey off with a bite to the neck, severing the arteries and closing the windpipe.

Although the large ‘sabre teeth’ of Smilodon appear to be devastating weapons, they were actually very fragile for canine teeth. Just as you can use a lever to magnify force to lift an object, the oversized teeth would also have been susceptible to magnified forces.

Smilodon also had weaker jaw muscles than many other large cats that had smaller teeth, perhaps as an adaptation to reduce exposure to potentially teeth breaking stresses. However, weaker muscles would also allow Smilodon to open its mouth wider, and as we shall see, that is a vital adaptation.

A key feature of the jaws is the enormously wide gape. Compared to one of today’s lion’s that can open their mouths to 60 degrees, Smilodon could double this by opening its mouth to 120 degrees.

Although impressive on paper, this is actually a very necessary adaption if it were to get full use of its teeth without also being handicapped by them. Considering that the teeth were up to 28centimetres long, the lower jaw would barely clear the bottom of the teeth if it could only open by 60 degrees.

Smilodon may have also been a delicate eater due to the two larger teeth getting in the way of the smaller canine teeth. This would mean that Smilodon had to take smaller bites from a carcass as the large teeth were not suitable for tearing off large chunks.

They may however have helped to hold bones in place while Smilodon chewed on them with its rear teeth, although the weaker jaw muscles probably meant that Smilodon did not spend much time trying to crack open bones.

Returning to the above proposal of pack hunting in Smilodon, there are two areas of support for this theory.

The first is the paleopathology of Smilodon remains. Many of these specimens show signs of injuries to bones and the areas of muscle attachment that are so serious they would take weeks, and even months to heal, and would be enough to prevent a Smilodon from actively hunting.

In solitary creatures these wounds would mean that the animal could not hunt and would actually starve to death, but many of the Smilodon specimens show that they healed. This means that the injured Smilodon had to get its food from somewhere while it recovered, and one explanation is that it was supported and fed by other members of the group. This behaviour can be observed in prides of lions today.

A second piece of support references a study of African carnivore reactions to the sounds of distressed animals. When the investigative team played back the sounds, they noticed that social carnivores would approach the sounds, whereas solitary ones would typically give them a wide birth.

This suggests that when smaller carnivores hear the distress calls, they know that not only are larger carnivores coming to investigate, they are coming in their numbers too. A smaller carnivore is smart enough to know that if it goes to an area where large predators are not just present but numerous, it will likely end up being killed and eaten too.

This scenario is quite plausible for the La Brea Tar Pits and the parallels that can be drawn between this study and the fossil evidence of la Brea, gives a very good indication to the social interaction of not just Smilodon, but other ancient predators such as dire wolves.

Further Reading

- – A new hypothesis to explain the method of food ingestion used by Smilodon californicus Bovard. – Tebiwa 12: 9–19. – G. J. Miller – 1969.

- – Behavioral implications of saber-toothed felid morphology. – Paleobiology 2 (4): 332–42. – W. J. Gonyea – 1976.

- – The status of Smilodon in North and South America. – Contributions in Science, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County 370: 1–15. – A. Berta – 1985.

- – Patterns of paravertebral ossification in the prehistoric saber-toothed cat. – American Journal of Roentgenology 148 (4): 779–782. – A. G. Bjorkengren, D. J. Sartoris, S. Shermis & D. Resnick – 1987.

- – Injuries and diseases in Smilodon californicus. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology (Supplement) 9: 24A. – F. Heald – 1989.

- – Relationships between North and South American Smilodon. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 10 (2): 158–169. – B. Kurten & L. Werdelinb – 1990.

- – Molar microwear and diet in large carnivores: inferences concerning diet in the sabretooth cat, Smilodon fatalis. – Journal of Zoology 222 (2): 319–40. – B. Van Valkenburg, M. F. Teaford & A. Walker – 1990.

- – Iterative evolution of hypercarnivory in canids (Mammalia: Carnivora): evolutionary interactions among sympatric predators. – Paleobiology 17 (4): 340–362. – B. Van Valkenburg – 1991.

- – Molecular phylogenetic inference from saber-toothed cat fossils of Rancho La Brea. – Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 89 (20): 9769. – D. N. Janczewski, N. Yuhki, D. A. Gilbert, G. T. Jefferson & S. J. O’Brien – 1992.

- – Tough times at la brea: tooth breakage in large carnivores of the late Pleistocene. – Science 261 (5120): 456–59. – B. Van Valkenburgh & F. Hertel – 1993.

- – Microwear on canines and killing behavior in large carnivores: saber function in Smilodon fatalis. – Journal of Mammalogy 77 (4): 1059–1067. – W. Anyonge – 1996.

- – Parietal depressions in skulls of the extinct saber-toothed felid Smilodon fatalis: evidence of mechanical strain. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 17 (3): 600–609. – G. L. Duckler – 1997.

- – Reconstructed facial appearance of the sabretoothed felid Smilodon. – Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 124 (4): 369–86. – M. Antón, R. García-Perea & A. Turner – 1998.

- – Sexual dimorphism, social behavior and intrasexual competition in large Pleistocene carnivorans. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22 (1): 164–169. – B. Van Valkenburgh & T. Sacco – 2002.

- – Assessing behavior in extinct animals: was Smilodon social?. – Brain, Behavior and Evolution 61 (3): 159–64. – S. McCall, V. Naples & L. Martin – 2003.

- – Isotopic evidence of saber-tooth development, growth rate, and diet from the adult canine of Smilodon fatalis from Rancho La Brea. – Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 206 (3–4): 303–310. – R. C. Feranec – 2004.

- – Rancho La Brea stable isotope biogeochemistry and its implications for the palaeoecology of late Pleistocene, coastal southern California. – Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 205 (3–4): 199–219. – J. B. Coltrain, J. M. Harris, T. E. Cerling, J. R. Ehleringer, M.-D.Dearing, J. Ward & J. Allen – 2004.

- – Growth rate and duration of growth in the adult canine of Smilodon gracilis and inferences on diet through stable isotope analysis. – Feranec Bull FLMNH 45 (4): 369–77. – R. C. Fennec – 2005.

- – Evolution of the extinct Sabretooths and the American cheetah-like cat. – Current Biology 15 (15): R589–R590. – R. Barnett, I . Barnes, M. J. Phillips, L. D. Martin, C. R. Harington, J. A. Leonard & A. Cooper – 2005.

- – Body Size of Smilodon (Mammalia: Felidae). – Journal of Morphology 266 (3): 369–384. – P. Christiansen & J. M. Harris – 2005.

- – Majestic killers: the sabre-toothed cats (Fossils explained 52). – Geology Today 22 (4): 150–157 – L. W. van den Hoek Ostende, M. Morlo & D. Nagel – 2006.

- – A first record of the Pleistocene saber-toothed cat Smilodon populator Lund, 1842 (Carnivora: Felidae: Machairodontinae) from Venezuela. – Asociación Paleontologica Argentina 43 (2). – D. Ascanio & R. Rincón – 2006.

- – Comparative bite forces and canine bending strength in feline and sabretooth felids: implications for predatory ecology. – Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 151 (2): 423–37 – P. Christiansen – 2007.

- – Supermodeled sabercat, predatory behavior in Smilodon fatalis revealed by high-resolution 3D computer simulation. – PNAS 104 (41): 16010–16015. – C. R. McHenry, S. Wroe, P. D. Clausen, K. Moreno & E. Cunningham – 2007.

- – Long in the tooth: evolution of sabertooth cat cranial shape. – Paleobiology 34 (3): 403–419. – G. J. Slater & B. V. Valkenburgh – 2008.

- – New postcranial remains of Smilodon populator Lund, 1842 from South-Central Brazil”. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia 11 (3): 199–206. – Mariela Cordeiro de Castro & Max Cardoso Langer – 2008.

- – Parallels between playbacks and Pleistocene tar seeps suggest sociality in an extinct sabretooth cat, Smilodon. – Biological Letters 5 (1): 81–85. – C. Carbone, T. Maddox, P. J. Funston, M. G. L. Mills, G. F. Grether & B. Van Valkenburgh – 2009.

- – Coincidence or evidence: was the sabretooth cat Smilodon social?. – Biology Letters 5 (4): 561–562. – C. Kiffner – 2009.

- – Sociality in Rancho La Brea Smilodon: arguments favour ‘evidence’ over ‘coincidence’. – Biology Letters 5 (4): 563–564. – B. Van Valkenburgh, T. Maddox, P. J. Funston, M. G. L. Mills, G. F. Grether & C. Carbone – 2009.

- – Sexual dimorphism and ontogenetic growth in the American lion and sabertoothed cat from Rancho La Brea. – Journal of Zoology 280 (3): 271–279. – J. Meachen-Samuels & W. Binder – 2010.

- – Radiographs reveal exceptional forelimb strength in the sabertooth cat, Smilodon fatalis. – PLoS ONE 5 (7): e11412. – J. A. Meachen-Samuels & B. Van Valkenburgh – 2010.

- – New saber-toothed cat records (Felidae: Machairodontinae) for the Pleistocene of Venezuela, and the Great American Biotic Interchange. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 31 (2): 468– 478 – A. Rincón, F. Prevosti & G. Parra – 2011.

- – Sabretoothed Carnivores and the Killing of Large Prey. – PLoS ONE 6 (10): e24971. K. Andersson, D. Norman & L. Werdelin – 2011.

- – Implications of Diet for the Extinction of Saber-Toothed Cats and American Lions. – PLoS ONE 7 (12): e52453. – L. R. G. DeSantis, B. W. Schubert, J. R. Scott & P. S. Ungar – 2012.

- – Variation in craniomandibular morphology and sexual dimorphism in Pantherines and the sabercat Smilodon fatalis. – PLoS ONE 7 (10) – P. Christiansen & J. M. Harris – 2012.

- – Jaw function in Smilodon fatalis: a reevaluation of the canine shear-bite and a proposal for a new forelimb-powered class 1 lever model. – PLOS ONE. 9 (10): e107456. – R. Macchiarelli, J. G. Brown – 2014.

- – Using a novel absolute ontogenetic age determination technique to calculate the timing of tooth eruption in the saber-toothed cat, Smilodon fatalis. – PLOS ONE. 10 (7): e0129847. – M. . Mihlbachler, M. A. Wysocki, R. S. Feranec, Z. J. Tseng & C. S. Bjornsson – 2015.

- – The Addition of Smilodon fatalis (Mammalia: Carnivora: Felidae) to the Biota of the Late Pleistocene Carpinteria Asphalt Deposits in California, with Ontogenetic and Ecologic Implications for the Species, by Christopher A. Shaw & James P. Quinn. In. Science Series 42: Contributions in Science. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (A special volume entitled La Brea and Beyond: the Paleontology of Asphalt–Preserved Biotas in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County’s excavations at Rancho La Brea): 91–95. – John M. Harris – 2015.

- – Paleobiology of sabretooth cat Smilodon population in the Pampean Region (Buenos Aires Province, Argentina) around the Last Glacial Maximum: Insights from carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes in bone collagen. – Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 449: 463–474. – H. Bocherens, M. Cotte, R. Bonini, D. Scian, P. Straccia, L. Soibelzon & F. J. Soibelzon – 2016.

- – First fossil footprints of saber-toothed cats are bigger than Bengal tiger paws. – Science. – Sid Perkins – 2016.

- – Skeletal trauma reflects hunting behaviour in extinct sabre-tooth cats and dire wolves. – Nature Ecology & Evolution. 1 (5): 0131. – C. Brown, M. Balisi, C. A. Shaw & B. van Valkenburgh – 2017.

- – Did saber-tooth kittens grow up musclebound? A study of postnatal limb bone allometry in felids from the Pleistocene of Rancho La Brea. – PLOS ONE. 12 (9): e0183175. – K. Long, D. Prothero, M. Madan, V. J. P. Syverson & T. Smith – 2017.

- – First record of Smilodon fatalis Leidy, 1868 (Felidae, Machairodontinae) in the extra-Andean region of South America (late Pleistocene, Sopas Formation), Uruguay: Taxonomic and paleobiogeographic implications. – Quaternary Science Reviews. 180: 57–62. – A. Manzuetti, D. Perea, M. Ubilla & A. Rinderknecht – 2018.

- – Smilodon: The Iconic Sabertooth (Smilodon from South Carolina: Implications for the taxonomy of the genus ed.). – Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 76–95. – L. Werdelin, H. G. McDonald & C. A. Shaw – 2018.

- – Late Pleistocene records of felids from Medicine Hat, Alberta, including the first Canadian record of the sabre-toothed cat Smilodon fatalis. – Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 56 (10): 1052–1060. – A. R. Reynolds, K. L. Seymour & D. C. Evans – 2019.

- – Causes and Consequences of Pleistocene Megafaunal Extinctions as Revealed from Rancho La Brea Mammals. – Current Biology. 29 (15): 2488–2495. – Larisa R.G. DeSantis, Jonathan M. Crites, Robert S. Feranec, John M. Harris, Gary T. Takeuchi & Thure E. Cerling – 2019.

- – Static scaling and the evolution of extreme canine size in a saber-toothed cat (Smilodon fatalis). – Integrative and Comparative Biology. 59 (5): 1303–1311. – D. M. O Brien – 2019.

- – Computed tomography reveals hip dysplasia in Smilodon: Implications for social behavior in an extinct Pleistocene predator. – bioRxiv Preprint. – Mairin A. Balisi, Abhinav K. Sharma, Carrie M. Howard, Christopher A. Shaw, Robert Klapper & Emily L. Lindsey – 2020.

- – An extremely large saber-tooth cat skull from Uruguay (late Pleistocene–early Holocene, Dolores Formation): body size and paleobiological implications. – Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 44 (2): 332–339. – A. Manzuetti, D. Perea, W. Jones, M. Ubilla & A. Rinderknecht – 2020.