In Depth

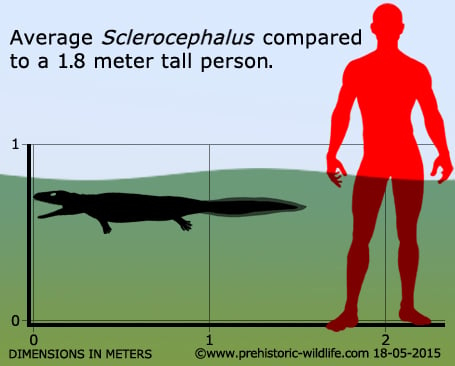

Anyone interested in the temnospondyl amphibians would do well to study the Sclerocephalus genus, as it is one of the few temnospondyl genera which actually gives us definitive clues about the lifestyles of these amphibians.

There are many individuals of Sclerocephalus known, and between then various life stages are represented. When newly hatched, Sclerocephalus larvae would have been entirely aquatic, and they possessed a proportionately longer tail than what adults had to provide more efficient locomotion through the water. During this stage of their lives the juveniles also had proportionately larger eyes than adults, and probably also the presence of external gills. As individuals matured, Sclerocephalus began to rely more upon their lungs than their external gills, and the tail shortened as the limbs began to take a greater role in locomotion, especially for periods spent on land.

Sclerocephalus were certainly capable of leaving the water and walking around on land, but they were still well adapted to life in the water. Sclerocephalus are known to have still had lateral lines, a line of sensory organs that ran down the length of the body identical to the lateral lines of fish. This would have allowed Sclerocephalus to detect things like pressure changes in the water so that they could be aware of other creatures moving through the water around them, even when the water was to murky for them to see.

At the top of the skull is a clearly defined pineal foramen, which in simpler terms is a small hole in the top of the skull. This would have allowed for what herpetologists call a ‘pineal eye’, a photosensitive (light sensitive) organ that triggered melatonin production from the pineal gland. The amount of melatonin produced would then vary according to the length of the day light hours, which could trigger certain behavioural activates depending upon the time of year. This is why anyone who keeps creatures with similar organs such as lizards as pets will steadily change the lengths of exposure to things such as artificial lamps in order to trigger behaviours such as breeding or even hibernation.

Sclerocephalus is also one of the few temnospondyl amphibian genera where we can definitely say what they ate. Remains of other amphibian genera including Micromelerpeton and Branchiosaurus have both been found included with the stomach contents of Sclerocephalus as well as the bony fish Paramblypterus, which together suggests that Sclerocephalus were opportunistic predators.

Sclerocephalus is the type genus of its own group, the Sclerocephalidae, though at the time of writing it is the only member genus of this group. Sclerocephalus was long thought to be related to the eryopoid temnospondyls (those closer to Eryops). More modern analysis of the genus however has led to the wider consensus that the genus is related to the archegosauroids.

The Permian period when Sclerocephalus lived saw the broken continents of the world coming together to form the supercontinent of Pangaea. This single large land mass meant a great reduction of water within inland areas, and many of the swamps and waterways soon dried out and became more arid. This change in ecosystem meant the demise of most of the temnospondyl amphibians like Sclerocephalus during the Permian, though a few exceptions such as Koolasuchus are known to have survived until the Cretaceous in the isolated wetland remnants that survived the Permian and subsequent break up of Pangaea.

Further Reading

- Revision von ‘Sclerocephalus haeuseri’ (Goldfuss) 1847 (Stem-Stereospondyli) - K. Kratschmer - 2004. - The stapes and middle ear of the Permo-Carboniferous tetrapod Sclerocephalus - R. R. Schoch - 2002. - The early larval ontogeny of the Permo-Carboniferous temnospondyl Sclerocephalus, R. R. Schoch - 2003. - Osteology and relationships of the temnospondyl genus Sclerocephalus, R. R. Schoch & F. Witzmann - 2009. - Sclerocephalus jogischneideri n. sp. (Eryopoidea, Amphibia) aus dem Unterrotliegenden (Unterperm) des Th�ringer Waldes - R. Werneburg - 1992. – The early larval ontogeny of the Permo-Carboniferous temnospondyl Sclerocephalus. – Palaeontology, 46: 1055-1072. – R. R. Schoch – 2003. – Revision von ‘Sclerocephalus haeuseri’ (Goldfuss) 1847 (Stem-Stereospondyli). – Geowissenschafftliche Beitr�ge zum Saarpf�lzischen Rotliegenden, 2: 1-52. – K. Kr�tschmer – 2004. – Osteology and relationships of the temnospondyl genus Sclerocephalus. – Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 157(1): 135–168. – R. R. Schoch & F. Witzmann – 2009.