Discovery and classification history of Saurophaganax

Saurophaganax has a complicated taxonomic history due to the fact that it is still only known from very partial remains, some of which bear a strong resemblance to the smaller but more common Allosaurus.

This history dates back to the discovery of the first material over 1931 and 1932 when John Willis Stovall recovered them from Kenton, Oklahoma.

The remains were first named Saurophagus maximus in a 1941 article by Grace Ernestine Ray; however the official name description did not happen until 1950.

In 1987 a lectotype (a bone used to identify further remains) was established and based upon a tibia (lower leg bone) designated OMNH 4666.

It was eventually realised that the genus name Saurophagus had actually been used back in 1831 to name a type of tyrant-flycatcher (flycatchers are passerine birds common throughout the Americas), and so a new name was required for the genus.

In 1995 Daniel Chure named the remains as Saurophaganax, changing the original name from ‘lizard-eater’ to ‘lizard-eating master’.

Chure did not treat this as renaming however, and rather than using the previous lectotype of the tibia, he designated a holotype based upon a vertebra (OMNH 01123.

Not long after this however a new theory came forward that Saurophaganax actually represented an exceptionally large species of Allosaurus on the basis that all of the known bones of Saurophaganax (with the exception of the vertebrae) were very similar to previously discovered Allosaurus material.

As such the proposal was to rename Saurophaganax as a new species of Allosaurus, A. maximus.

Today while some palaeontologists do this, it seems that most prefer to recognise Saurophaganax as its own genus.

The vertebrae are the key points in question here as they are quite different to those known from Allosaurus.

Additionally not all of the bones are known for Saurophaganax and it is currently difficult to tell if the vertebrae are the only difference between Saurophaganax and Allosaurus.

Despite this however, Allosaurus does seem to be the dinosaur closest in form to Saurophaganax, and missing elements in reconstructions of the latter are based upon Allosaurus parts scaled up to fit the larger frame of Saurophaganax.

Saurophaganax the dinosaur

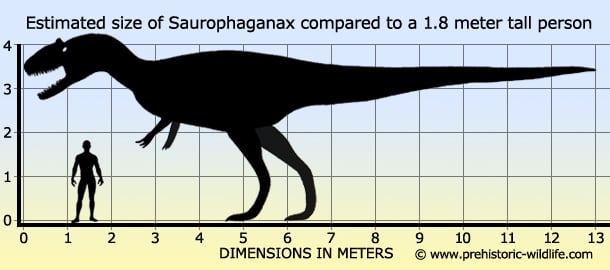

At around thirteen meters long Saurophaganax was exceptionally large for a Jurassic theropod, and could have rivalled both Tyrannosaurus and Giganotosaurus of the Cretaceous for size.

This large size would have seen Saurophaganax living as the dominant predator of late Jurassic North America, but the price of being such a large creature means that they would not have been as numerous as smaller predatory dinosaurs.

This is a simple principal based upon the fact that a larger body requires a proportionately greater amount of food than exactly the same body on a smaller scale.

As such larger animals are usually restricted to smaller populations as not to exhaust the amount of available food (or in the case of Saurophaganax, prey) in any given ecosystem.

Currently the fossil record supports this idea as Saurophaganax is represented by a tiny amount of fossil material when compared to other theropods like Allosaurus (possibly one of the most common theropods of the late Jurassic).

Despite this it should be remembered that Saurophaganax may have been more common than the fossil record suggests, and that in life not many Saurophaganax died in ways that allowed them to become fossilised.

Additionally the same fact that it was such a large dinosaur means that it is less likely that complete remains will be found in the future as larger bodies take more material to bury them and protect them from both scavengers and environmental conditions.

There always seems to be a predatory niche for a small number of large predators to be present in an ecosystem from Saurophaganax at the end of the Jurassic, Acrocanthosaurus of the early to mid-Cretaceous to finally the tyrannosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous.

The large size of Saurophaganax however has led to some accusations that it would have been slower than other predators and may have leaned more towards scavenging than actual hunting.

Saurophaganax may have even been a specialist scavenger that waited for other large theropod dinosaurs to take down large prey that could supply Saurophaganax with sufficient food while these predators were not actually being big enough to challenge Saurophaganax itself.

While the above scenario is a plausible one, it may only represent one facet of the behaviour of Saurophaganax.

Predators after all will steal kills from smaller and less powerful predators while remaining capable of killing their own prey when they have to.

This can be seen today with the lions of Africa taking prey from other but smaller cats to grizzly bears taking on a pack of wolves to take their latest kill, and even though they display scavenging behaviour, they are also well documented making their own kills.

Going back to the Jurassic of North America and Saurophaganax would have had plentiful access to large herbivorous dinosaurs that probably would have even been a lot slower than Saurophaganax despite its large size.

These would include sauropods like Diplodocus and Apatosaurus as well as armoured dinosaurs like Stegosaurus, a dinosaur that is known to have come into conflict with the smaller Allosaurus, so it seems quite likely that the larger Saurophaganax would have ventured to attack them as well.

Further Reading

– A reassessment of the gigantic theropod Saurophagus maximus from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Oklahoma, USA, by D. J. Chure. In, ixth Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems and Biota, Short Papers, China Ocean Press, Beijing 103-106. – A. Sun & Y. Wang (eds.).