In Depth

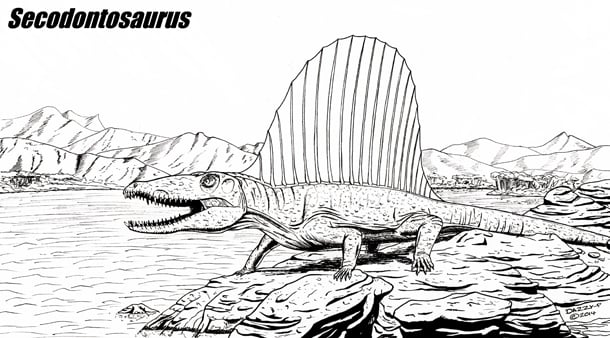

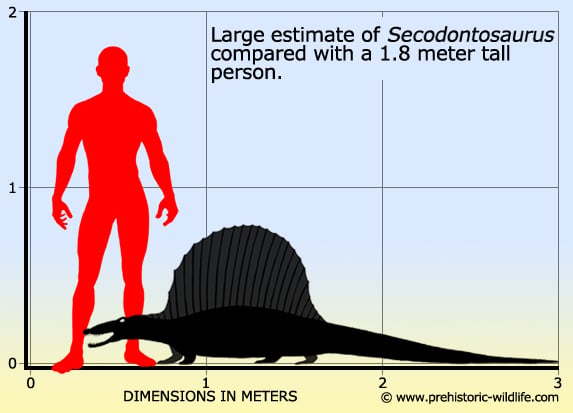

Secodontosaurus is a fantastic genus of pelycosaur as not only do individuals have large sails on their backs, but they have skulls that are quite different to the other sphenacodontid pelycosaurs that they are related to.

The naming of the Secodonotsaurus genus was actually a long time coming. The first Secodontosaurus fossils were actually named as a species of Theropleura, T. obusidens, by Edward Drinker Cope. Later though the type species of Theropleura was found to be a synonym to Ophiacodon, though what would be named as Secodontosaurus fossils could not be a part of the Ophiacodon genus. Then in 1907 another American palaeontologist named Ermine Case described a new fossil specimen as a new species of Dimetrodon, D. longiramus. Mainly based upon the description of a lower jaw, Dimetrodon longiramus would eventually become Secodontosaurus longiramus later in the twentieth century. The first actual mention of Secodontosaurus as a genus name came in 1925 when Samuel Williston listed the name as a member of the Ophiacodontidae, with reference to fossils initially mentioned in an earlier paper that he authored in 1916. The mention though was not a formal description of a genus however, and it was not until 1936 when Alfred Romer, a palaeontologist best remembered for his work with Permian era fauna, made the genus official with a proper description. In honour of Williston and his prior work with the genus, Romer also established the species S. willistoni.

The most famous sail-backed pelycosaur is without a doubt Dimetrodon, and it is this genus that Secodontosaurus has a particularly close association. The skull of Secodontosaurus is very different to the skull of Dimetrodon, but so far there is only one known difference in the post cranial skeleton between these two pelycosaurs. This difference is the axis vertebra, the second cervical (neck) vertebra that is the main pivot for the skull to move on the neck. In Dimetrodon, the neural spine of this vertebra is quite high, but the same vertebra in Secodontosaurus is proportionately lower. Aside from being a key physical difference, this may indicate that the head of Secodontosaurus had a greater range of backwards motion.

Unfortunately, Secodontosaurus is still only known from very incomplete post cranial remains which makes further differences hard to establish. The known elements though are seen as being very similar to Dimetrodon, so much so that it has been speculated more than once that fossils labelled as belonging to Dimetrodon and currently sitting in storage across different museums may actually represent further Secodontosaurus. Until more definitive Secodontosaurus post cranial fossils can be confirmed, reconstructions of Secodontosaurus usually rely upon comparative Dimetrodon remains to fill in the gaps.

The sail on the back of Secodontosaurus is also considered to have been similar in form to the one on Dimetrodon. Also like with Dimetrodon and other sail backed pelycosaurs for there are many, the sail of Secodontosaurus seems to have been for a primarily thermoregulatory purpose, warming and cooling the blood as needed in order to maintain optimum body temperature and by extension function. The sail may have also been a display device and although potentially similar in form to the sail of Dimetrodon, it may have been coloured or patterned in a different way as to be unique. This would then allow Secodontosaurus to recognise others of their own species, and not confuse them with he other kinds of sail-backed pelycosaurs that were active in the same area, which not only included Dimetrodon, but other genera such as Edaphosaurus and Ctenospondylus to name just two that we know about.

The key question concerning Secodontosaurus is why did it have different jaws? The simple answer is that Secodontosaurus probably had a different kind of prey specialisation. Others such as the aforementioned Dimetrodon and Ctenospondylus were probably predators of other medium to large vertebrates, probably even including other pelycosaurs, and their taller more robust skulls would have been better able to withstand the stresses imposed upon them from larger struggling prey. The jaws of Secodontosaurus are comparatively narrow and were better able to reach into places like gaps between rocks and perhaps even burrows, suggesting that Secodontosaurus may have been more specialised in hunting smaller vertebrate animals that were too small for other larger pelycosaurs to bother with. It would be also interesting to see if Secodontosaurus was a hunter of fish, since the long and thin jaws would have been quite suited to snatching fish out of shallow water in a similar manner to a crocodiles or possibly even the much later spinosaurid dinosaurs. A reduction in the size of the neural spine of the axis vertebra may have increased the range of up and down pitching of the head allowing Secodontosaurus to more easily lift a fish up out of the water, though such an adaptation would have also been of a benefit if Secodontosaurus spent their time pulling animals up and out of burrows and other tight spaces.

The smaller neural spine of the axis vertebra of Secodontosaurus could also be an argument for Secodontosaurus not specialising in the hunting of larger animals, since the taller neural spine of the axis vertebra of Dimetrodon would have been a larger attachment point of muscle to hold the head steady when dealing with large prey that was putting up a fight. Therefore, Secodontosaurus may not have had such an enlarged neural spine, because it didn’t require one. A lower skull form would also mean less room for the jaw closing muscles which means that the bite of Secodontosaurus would not have been as strong as other sphenacodontid pelycosaurs that had the more characteristic deep skulls. This further infers that Secodontosaurus was better suited to dealing with smaller animals than larger ones which may have been heavy and strong enough to break free from the mouth grip of a Secodontosaurus.

Further Reading

- Second contribution to the History of the Vertebrata of the Permian Formation of Texas - Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 19: 38–58. - Edward Drinker Cope - 1880. - Revision of the Pelycosauria of North America. - Carnegie Institution of Washington 55:3-176 - E. C. Case - 1907. - The osteology of some American Permian vertebrates, II - Contribution from Walker Museum 1: 165–192. - Samuel W. Williston - 1916. - Studies on American Permo-Carboniferous tetrapods - Problems of Paleontology, USSR 1: 85–93. - A. S. Romer - 1936. - Review of the Pelycosauria - Geological Society of America Special Paper 28: 1–538. - A. S. Romer & L.I Price - 1940. - The cranial anatomy and relationships of Secodontosaurus, an unusual mammal-like reptile (Pelycosauria: Sphenacodontidae) from the early Permian of Texas - Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 104: 127–184. - R. R. Reisz, D. S. Berman & D. Scott - 1992. - Interrelationships of basal synapsids: cranial and postcranial morphological partitions suggest different topologies - R. J. Benson - 2012.