In Depth

With study of Scelidosaurus going all of the way back until the mid-nineteenth century, Scelidosaurus is one of the oldest genera of dinosaur known. In addition to that, out of all the dinosaurs that are known from the British Isles, Scelidosaurus is represented by some of the most complete fossil material.

Scelidosaurus was once thought to have also lived in what is now the south western United States. This was based around the discovery of osteoderms in the Kayenta formation of Arizona, however, later analysis of these osteoderms has deemed them to be different from the known osteoderms of Scelidosaurus, and therefore Scelidosaurus remains only known from the British Isles. It is perhaps not impossible though that the osteoderms found in the Kayenta Formation may actually represent a close relative of Scelidosaurus.

The key significance of Scelidosaurus is that aside from being one of the first dinosaurs known to science, the genus represents one of the most primitive thyreophoran dinosaurs so far discovered, even though over one hundred and fifty years have passed since it was first described. However the true significance of Scelidosaurus was lost on the describer of the genus Richard Owen who perceived Scelidosaurus to have been semi aquatic and a piscivore, an eater of fish!

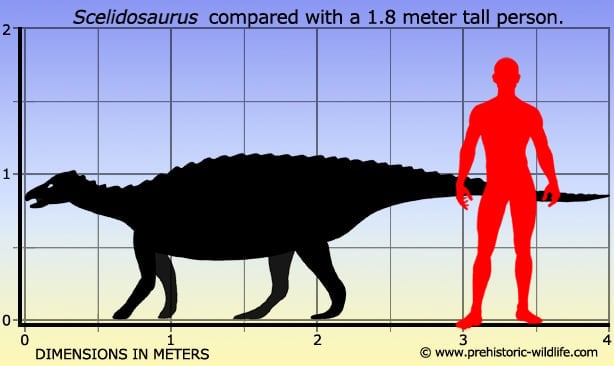

The truth about Scelidosaurus is that it was an ornithischian dinosaur that ate plants. Also, while the rear limbs are longer than the fore limbs, the fore limbs are still formed and long enough to suggest a weight bearing function, meaning that Scelidosaurus was mostly if not entirely quadrupedal. This also means that when given a choice, Scelidosaurus would have preferred to roam about on land.

Most of the study of Scelidosaurus has been focused on the osteoderms (scutes), plates of bone that fixed in place within the skin of Scelidosaurus rather than attaching directly to the skeleton. These osteoderms were arranged in rows that ran down the length of the body from head to tail. Individually the osteoderms were formed into ovals with a keel (ridge down the centre) on the outer side. The keel was also slightly higher on the posterior (end facing the tail) part of the osteoderm. The largest osteoderms were arranged in rows on the more exposed flanks (sides), while the osteoderms towards the underside were smaller and somewhat more conical.

It is most probable that the function of these osteoderms was to provide defence from the predators of the time such as theropod dinosaurs. The main killing weapons of these dinosaurs would have been the sharp teeth in the mouths as well as claws on their hands and feet. These body parts work by puncturing the skin and outer tissues to damage internal organs and bones. However, by having round plates of bone in the skin, it becomes significantly more difficult for a predator to only puncture the skin of its prey, but get a grip since the hard round surface of the osteoderm would cause the tooth/ claw to slide, potentially to even break. It has even been surmised that smaller granules of bone may have been present in between the spaces of the regular osteoderms to make the skin and underlying tissue even more resilient to the attacks of predators.

By having such a tough skin Scelidosaurus would have been impervious to the attacks of all but the largest and most powerful of predators of the time, and even then these predators may have preferred to hunt ‘softer’ prey. In time though predators adapt to hunt either a greater variety or specialise in just one type, and this could even include armoured dinosaurs. This would explain the forms of later thyreophoran dinosaurs such as the nodosaurs and ankylosaurs that took osteoderm armour to the extreme during the Cretaceous period, probably as an adaptation to increasingly powerful predatory dinosaurs appearing.

As already mentioned, Scelidosaurus represents one of the earliest appearances of a thyreophoran dinosaur. More famous thyreophorans include the stegosaurs which became common by the Late Jurassic, nodosaurs that are better known from the late Jurassic to the late Cretaceous and ankylosaurs that were most common in the late Cretaceous. We are fairly certain that the ankylosaurs evolved from the nodosaurs, with the main (but not only) difference being that ankylosaurs have tail clubs. We know that the stegosaurs are related to the nodosaurs and ankylosaurs with a more ancient and slightly murky ancestry that probably goes back to the early Jurassic when the two lines began to diverge from a common group of ancestors.

Unfortunately we still don’t know exactly how Scelidosaurus was related to these later groups. It would be no great surprise to learn that the osteoderm arrangement of Scelidosaurus and similar dinosaurs was the precursor to the thicker and more complete armour of the nodosaurs. Care should be taken before assuming a link though since the similarity may simply be the result of two groups facing the same ecological survival conditions. Only greater study, as well as the discovery of more transitional forms that show a steady adaptation from one form into another could help to determine the truth.

In the past there has been more than one species of Scelidosaurus named, though currently the only species considered to be valid is the type species S. harrisonii. One former species S. oehleri was established from the fragmentary remains of Tatisaurus, however, many palaeontologists have rejected this in favour of keeping Tatisaurus a distinct genus.

Further Reading

- A monograph of a fossil dinosaur (Scelidosaurus harrisonii, Owen) of the Lower Lias, part I. - Monographs on the British fossil Reptilia from the Oolitic Formations 1 pp 14 - Richard Owen - 1861. - A monograph of the fossil Reptilia of the Liassic Formations. Part 2. A monograph of a fossil dinosaur (Scelidosaurus harrisonii Owen) of the Lower Lias. - Palaeontographical Society Monographs. Part 2. pp. 1-26 - Richard Owen - 1863. - The Mesozoic reptiles of Dorset: Part Two - Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society, for 1958 80: 52-90 - J. B. Delair - 1959. - The Jurassic dinosaur Scelidosaurus harrisoni, Owen. - Palaeontology 11 (1), 40-3 - B. H. Norman - 1968. - The development of the remains of a small Scelidosaurus from a Lias nodule - Museums Journal, 67: 315–321 - A. E. Rixon - 1968. - Relationships of the lower Jurassic dinosaur Scelidosaurus harrisonii - Journal of Paleontology. July 1977; v. 51; no. 4; p. 725-739 - R. A. Thulborn - 1977. - New scelidosaur remains from the Lower Lias of Dorset - Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society 110: 165 & 167 - P. C. Ensom - 1989. - Presence of the dinosaur Scelidosaurus indicates Jurassic age for the Kayenta Formation (Glen Canyon Group, northern Arizona) - Geology. May 1989, v. 17; no. 5; p. 438-441 - K. Padian - 1989. - Scelidosaurus harrisonii Owen, 1861 (Reptilia, Ornithischia): proposed replacement in inappropriate lectotype - Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature, 49: 280–283 - A. J. Charig & B. H. Newman - 1992. - Scelidosaurus harrisonii Owen, 1861 (Reptilia, Ornithischia): lectotype replaced - Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 51: 288 - International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature - 1994. - The Thyreophoran Dinosaur Scelidosaurus from the Lower Jurassic Lufeng Formation, Yunnan, China. pp. 81-85, in M. Morales (ed.) The Continental Jurassic. Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin 60. - S. G Lucas - 1996. - Professor Richard Owen and the important but neglected dinosaur Scelidosaurus harrisonii - Historical Biology, 14: 235–253 - D. B. Norman - 2000. - A New Specimen of the Thyreophoran Dinosaur cf. Scelidosaurus with Soft Tissue Preservation. - Palaeontology, Vol. 43, Part 3, 2000, pp. 549-559 - D. M. Martill, D. J. Batten & D. K. Loydell - 2000. - Dinosaurs of Great Britain and the role of the Geological Society of London in their discovery: basal Dinosauria and Saurischia, - Journal of the Geological Society, London, 164: 493–510 - D. Naish & D. M. Martill - 2007. - Reconsidering the status and affinities of the ornithischian dinosaur Tatisaurus oehleri Simmons, 1965 - Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 150 (4): 865–874 - D. B. Norman, R. J. Butler & S. C. R. Maidment - 2008. – Scelidosaurus harrisonii from the Early Jurassic of Dorset, England: cranial anatomy. – Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 188 (1): 1–81. – David B. Norman – 2020.