In Depth

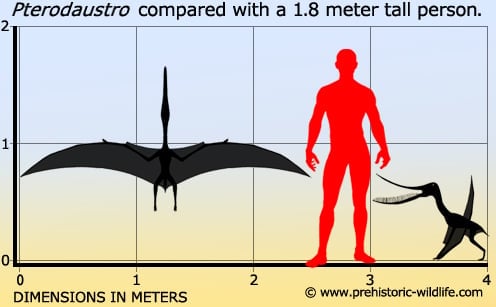

The discovery of Pterodaustro was a fantastic find, as not only was it the first pterosaur to be discovered in South America, here was a pterosaur that filtered for food in a similar manner to a modern day flamingo. This is evidenced by the strongly upwards curing beak that instead of having more normal pterosaur teeth, Pterodaustro had a series of several hundred bristle like teeth that extended upwards from the lower jaw. The upper jaw did not have these bristle teeth, but could be closed without contacting or damaging them.

This jaw arrangement, unusual amongst the pterosaurs, would have allowed Pterodaustro to scoop up a beak full of water that contained food sources such as invertebrates and plankton. The bristle teeth would allow the water to drain out while keeping small invertebrates inside so that they could be swallowed. The presence of small globular teeth in the upper jaw suggests that the invertebrates were probably mashed before they were swallowed.

Another first for Pterodaustro is the presence of gizzard stones. Considering a diet of small invertebrates, these stones may have spilt and broken the hard exoskeletons of the invertebrates to allow for more efficient digestion. They may however simply have been swallowed along with its food, as only a small number of specimens show these stones.

Because flamingos have the same food sources, they also absorb their pink pigment from their food, and because of this, it has been suggested that Pterodaustro may have also had a pink hue to its body. However a 2005 study by Shawkey and Hill has cast serious doubt upon the idea that Pterodaustro may have been pink as the result of chosen diet.

The scleral rings of Pterodaustro indicate a nocturnal lifestyle. This may be to avoid feeding competition with other creatures, or avoid daytime predators that would have had an easy time spotting a pink Pterosaur. It may have also simply been a case of its food supply being more plentiful at night, or even a combination of these things.

Because of the huge number of discovered remains, the growth cycle of Pterodaustro can be easily established. The fastest period of growth took place over the first two years, and in this time the individual would reach up to half its full size. It is then thought that they reached reproductive maturity, although they would still continue to grow for up to a further five years until fully grown. A fossilised Pterodaustro egg, sixty millimetres long and twenty-two millimetres wide has also been found to contain a Pterodaustro embryo inside.

Further Reading

– Pterodaustro guinazui gen. et sp. nov. Pterosaurio de la Formacion Lagarcito, Provincia de San Luis, Argentina y su significado en la geologia regional (Pterodactylidae) [Pterodaustro guinazui gene. et sp. nov. Pterosaur of Lagarcito Training, Province of San Luis, Argentina and its significance in regional geology (Pterodactylidae)]. – Acta Geologica Lilloana 10: 209–225. – Jose F. Bonaparte – 1970. – The design of mineralised hard tissues for their mechanical functions. – Journal of Experimental Biology 202 (23): 3285–3294. – John D. Currey – 1999. – Argentinian unhatched pterosaur fossil. – Nature 432 (7017): 571–572. – L. M. Chiappe, L. Codorni�, G. Grellet-Tinner & D. Rivarola – 2004. – Carotenoids need structural colours to shine. – Biology Letters 1 (2): 121–4. – M. D. Shawkey & G. E. Hill – 2005. – Developmental growth patterns of the filter-feeder pterosaur, Pterodaustro guinazui. – Biology Letters 4 (3): 282–285. – A. Chinsamy, L. Codorni� & L. M. Chiappe – 2008. – First occurrence of gastroliths in Pterosauria (Early Cretaceous, Argentina). – XXIV Jornadas Argentinas de Paleontolog�a de Vertebrados. – L. Codorni�, L. M. Chiappe, A. Arcucci & A. Ortiz-Suarez – 2009. – The first pterosaur 3-D egg: Implications for Pterodaustro guinazui nesting strategies, an Albian filter feeder pterosaur from central Argentina. – Geoscience Frontiers. – G. Grellet-Tinner, M. Thompson, L. E. Fiorelli, E. S. Arga�araz, L. Codorni� & E. M. N. Hechenleitner – 2014.