In Depth

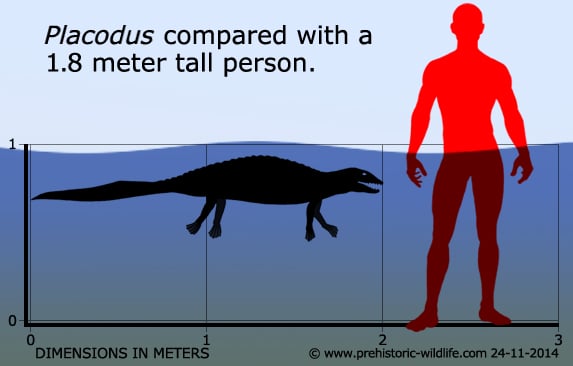

Placodus is one of the most often represented reptiles of the placodont group, and the most common of the ‘unarmoured’ variety that seemed to be similar to marine iguanas. Unlike the algae eating marine iguana however, Placodus was a dedicated durophagous shellfish eater. In its search for food it used specialised forward pointing incisors to grip and pluck things like bivalves and crustaceans off the sea floor before taking them into the back of its mouth. Here a battery of flat crushing teeth that extended across the palate broke up the shell so that Placodus could swallow the soft bodied organism within.

As a marine reptile Placodus seems to have been adapted for swimming while still retaining features that saw it still able to move about on land, although it does not seem especially able to do one or the other. In the water Placodus would have relied upon its laterally compressed (sideways flattened) tail for its main propulsion, while the legs and possibly webbed feet could have been used for steering by pushing out against the water to turn the body in the opposite direction. This method meant that Placodus’s body and swimming method was not suitable for pelagic life in the open ocean, but really it would not have had to swim out this far as the greatest abundance of shell fish would be close to the coast and in the sunlit layers.

Placodus seems to have relied upon neutral buoyancy to take most of the effort out of swimming. Evidence for this comes from the dense bones of its skeleton as well as scutes (bony armour) that formed a ridge along its back, all helping to increase its body weight and density. The result of this is that Placodus could effectively sink itself without struggling to keep a light air filled body on the sea floor.

Feeding behaviour is thought to have been fairly simple with Placodus using its legs to hover in the water above some shellfish as it picked them out with its forward teeth. Placodus also had a parietal eye (sometimes called a pineal eye) on top of its head. A parietal eye does not work like a regular optic eye that you see out of, but is instead a photoreceptive (light sensitive) organ. Usually these trigger specific behaviour in accordance with increasing and decreasing photo periods (i.e. longer to shorter hours of daylight), but in Placodus it has also been suggested to help it to orient itself correctly when it needed to return to the surface, something that would have been important when hovering face down towards the sea floor. The body of Placodus was not especially flexible, in part caused by the way the vertebrae connected together which resulted in a semi rigid spine that gave good support when in the water, but was very poor for land movement. The large ribs of Placodus also bent backwards to provide additional cover for the lower body. Although often envisioned as armour, this may have been for support of the body when on land as opposed to just protection from predators. The same legs that were used for swimming were not especially large, and given the large round bulk of the body, Placodus may have had to push itself along the ground with the ribs helping to protect the lower organs like the intestines from this ground contact. Altogether the aquatic adaptations of Placodus meant that it would have been a cumbersome animal when compared to its exclusively terrestrial counterparts, and as such it probably did not venture too far from the water line as doing so would increase the amount of energy required going to and from the water while increasing the chance of contact with larger land predators.

For a long time Placodus was thought to be an exclusively European genus, but the naming of the second species, P. inexpectatus, in China in 2008 shows that while Placodus was not a strong ocean going swimmer, it was perfectly capable of following Triassic coastlines to colonise new parts of the globe.

Further Reading

– Description of the Skull and Teeth of the Placodus laticeps, Owen, with Indications of Other New Species of Placodus, and Evidence of the Saurian Nature of That Genus. – Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Volume 148. – Owen. – On the skull of Placodus gigas and the relationships of the Placodontia. -Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology vol 7. – Hans-Dieter Sues – 1987. – Palaeoecology of Placodus gigas (Reptilia) and other placodontids — Middle Triassic macroalgae feeders in the Germanic Basin of central Europe — and evidence for convergent evolution with Sirenia. – Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology vol 285 – Cajus G. Diedrich – 2010.